Greater Cairo

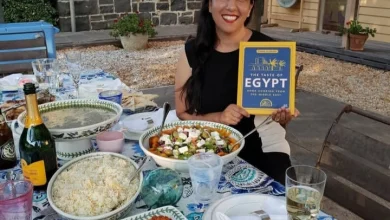

From Chalkboards to AI: Dr. Linda Herrera Decodes the Century-Long War for Egypt’s Schools

An American social anthropologist explores how the classroom has become a modern battlefield for power, identity, and the struggle for the Egyptian mind.