The Egyptian Jilbab: From Pharaohs to Fashion, A 5,000-Year Style Legacy

From the very dawn of Egyptian civilisation, as people forged a new relationship with their environment, the long linen garment emerged as a cornerstone of their identity. More than mere clothing, this fabric was a testament to their ingenuity. The Egyptians mastered the cultivation of flax, weaving its fibers into lightweight linen perfect for the climate,a tangible symbol of their advanced agricultural knowledge.

At the heart of this ancient wardrobe was the izar or shandit, a graceful wrap worn around the body. Its design was a marvel of both form and function, allowing for freedom of movement while simultaneously embodying the culture’s core values. The precise drape of the garment reflected a deep social discipline and a profound respect for the cosmic order that governed the Egyptian worldview.

The roots of Egyptian clothing since the dawn of history

Priests wore white linen as a symbol of purity associated with rituals. Peasants wore practical versions that allowed them to work the land freely without restrictions. With the development of the Old and then Middle Kingdom, long robes with fine pleats emerged, which were a sign of prestige and elegance, and the clothes of the nobility were decorated with threads and colors. White remained the dominant color, as it combines beauty and functionality in a hot and sunny environment.

This blend of function and symbolism made clothing part of the Egyptian identity, which was based on the boundary between daily life and religious rituals. Purity and the wearing of clean clothes were a prerequisite for entering temples and an essential component of rituals associated with death and resurrection. Through papyri, statues, and inscriptions, we can read the entire history of Egyptian clothing: how it originated, changed, and remained true to its essence despite its many forms.

Thus, the contemporary galabiya stands on a continuum that begins with that first moment when the Egyptians wove linen fibers. Over thousands of years, it has become a profound symbol of a civilization whose thread has never been broken.

The garments of power in the monarchy and the connotations of prestige

At the heart of the ancient Egyptian state, where politics was shaped and religious symbolism was reproduced. Royal clothing was a visual tool that carried a clear message of power and sanctity. Since before the dynasties, the Na’mar painting and the king’s possessions revealed the royal costume, which was tightly wrapped around the body. It carried the beginnings of the idea of an appearance that distinguished the king from the rest of society.

With the development of the state, the royal chendit became a highly complex garment, expertly wrapped around the waist and adorned with delicate folds that displayed the craftsmanship and status of the wearer. In the modern state, the transparent, long, and loose haik emerged, flowing around the body in a complex manner that reflected the artistic development in the textile industry. It is fastened with a calculated knot, while the symbolic tail of the bull appears as a sign of royal power.

These garments were not merely luxurious clothing, but were laden with political and religious connotations: the color, the number of folds, the type of weave, the location of the knot, and every detail spoke the language of authority. In the inscriptions, the image of the king is repeated in different garments for military, religious, ceremonial, or official occasions, reflecting the diversity of roles that the king embodied.

The royal costume was a constant declaration of the pharaoh’s position as a mediator between heaven and earth. As a political leader, he imposed order through powerful visual symbolism. The evolution of Egyptian clothing cannot be understood without considering this royal influence, which was reflected in the clothing of priests and even the general public.

Hence, the galabiya—whose name has changed over the centuries—became a simplified extension of a long line that combined authority, symbolism, and function.

The Coptic era: new modesty for an ancient heritage

With the arrival of Christianity in Egypt, the event was not merely a religious conversion, but a broad cultural transition that clearly affected all aspects of life, including clothing. The need for modesty emerged as a spiritual value. Wide robes and long jilbabs with wide sleeves appeared, combining comfort and modesty.

Although Coptic fashion was influenced by Greek, Roman, and Byzantine styles, it retained its authentic Egyptian spirit, with simple lines, natural materials, and calm colors. Textile decorations became an essential element, with simple patterns, natural materials, and calm colors. textiles became an essential element, appearing in the form of crosses or floral and geometric motifs woven into the fabric rather than on top of it, symbolizing the union of body, soul, and dress.

Coptic art—in frescoes, tombs, and manuscripts—provided an important visual reference for this period. Men are depicted in loose-fitting clothing, reflecting a social shift toward modesty. At the same time, there are clear influences from the Greeks and Romans.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint exact time periods for Coptic clothing due to historical overlap, broad outlines indicate a gradual evolution in dress. Starting with relatively short shirts to long robes, and from limited colors to bolder variations in decoration. However, it remained less flamboyant and more simple than the Byzantines, whose clothing was dominated by stones and jewels. Nevertheless, the essence of Coptic clothing remained consistent with the ancient Egyptian mood, which favored simplicity of form and stability of detail. This mood continued later in the Islamic jilbab, then the rural galabiya. This made the Coptic era a key link in the chain of Egyptian costume development, connecting the past to the Islamic present without interruption.

The Islamic era… A symbol of identity and modesty

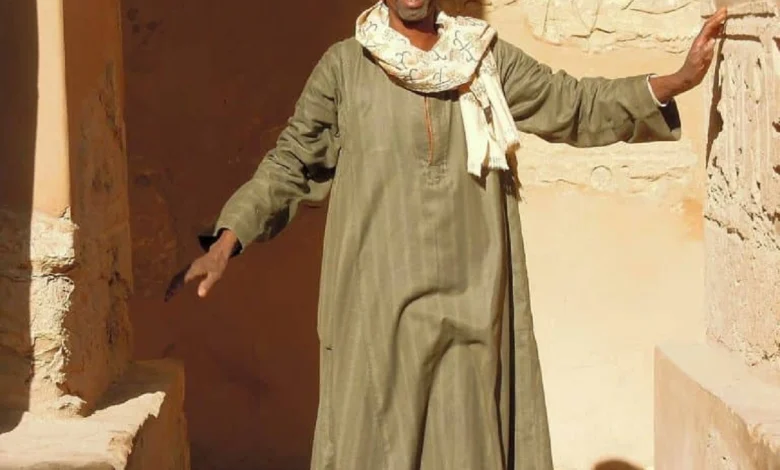

With the advent of Islam, Egypt rebuilt its relationship with clothing, but without severing its ties to its original heritage. The Islamic jilbab appeared long and loose, covering the entire body and reflecting the values of modesty and humility. However, it retained the ancient Egyptian characteristics of spaciousness, simplicity of cut, and ease of movement.

In cities, especially Cairo and Fustat, it acquired more refined details—such as embroidery on the sleeves and chest area—reflecting urban taste and the upper classes’ connection to advanced textile industries. In the countryside, Upper Egypt, and the oases, it remained primarily dark colors that could withstand work in the sun, a loose fit suitable for moving around on the land, and locally woven cotton fabrics.

Along with the jilbab, men wear shawls and cloaks as accessories that complement their social identity; with balga as footwear, the shawl expresses the region. The balga represents the established presence of the Egyptian peasant, who has preserved the simplicity of his tools.

With the flourishing of commercial life in the Islamic era, the jilbab became everyday wear, but it also became an essential part of religious and social occasions such as Eid prayers, Mawlid celebrations, weddings, and funerals. It became a symbol of social class, with the material, color, and style of tailoring differing between farmers, merchants, scholars, and employees.

Thus, the jilbab was not merely a religious response to modesty, but a purely Egyptian reproduction of an ancient heritage to which Islamic civilization breathed new life. It became the basis for the traditional jilbab that we know today.

The modern era: between the resilience of heritage and changing public taste

In the 19th century, Cairo and Alexandria began to be influenced by European fashion, with trousers, shirts, and suits becoming the basis of urban clothing. However, the countryside and Upper Egypt did not get swept up in the new trends, but rather preserved their origins as more suitable for the conditions of work, land, and climate. Thus, the galabiya became established as an authentic rural and Upper Egyptian symbol, associated with men who worked the land and lived near the Nile.

In the 20th century, the galabiya took a prominent place in cinema, theater, and literature as the symbol of the struggling farmer, the Upper Egyptian proud of his dignity, and the traditional Egyptian man who combines chivalry and belonging. With the rise of the modern state and the opening of cities to international fashion, there remained a constant in rural and tribal communities that clung to the galabiya as a garment that did not change with fashion. there remained a constant in rural and tribal communities that clung to the galabiya as a garment that did not change with fashion.

With the development of communication in the 21st century, young people in cities began to view the galabiya from a new angle: a symbol of authenticity that could be reintroduced in a contemporary form. Galabiyas appeared, improved with precise stitching, and others were presented as an artistic experience at festivals or popular events. The old garment became part of a wave of heritage revival with a modern twist. Despite this diversity, the common factor remained its essence: comfort, spaciousness, and ease of movement. These are the same characteristics that the ancient Egyptians recognized thousands of years ago.

A mirror of Egyptian identity

Today, the Egyptian galabiya is more than just a garment; it is a rare thread that connects different eras of Egyptian history without interruption. What distinguishes it is not only its shape, but also the fact that it carries inherited social and cultural values: simplicity, respect for the body, connection to the land, and the ability to absorb external influences without losing one’s spirit.

The difference in colors between Upper Egypt, where dark colors are preferred, and the Delta, where bright colors are prevalent, is not only an aesthetic difference, but also a reflection of the culture of society. The same is true of the difference in the width of the sleeves, the width and length of the galabiya, and the way the shawl or belt is worn. These are all indicators of social and class affiliation.

Although modern fashion has changed clothing styles in cities, the galabiya has remained a symbol of cultural stability, combining function and identity. In a time of rapid change, the galabiya has become a cultural document that reflects Egypt’s collective memory: a past that has not disappeared and a present that is inseparable from its roots.