“Tales of Crossing”.. Folk Heritage in the Memory of War

Not all heroism is written in books; it lives on in stories that are told and novels that are passed down from generation to generation. The October 1973 victory was not just a military battle, but an event of great importance that transcended the boundaries of trenches and cannons. It became part of the Egyptian people’s consciousness, engraved in the hearts of every family, and recounted by grandparents and parents to their children and grandchildren.

Alongside the official narratives documenting numbers, plans, and strategic movements, the people had their own stories, born from their experiences. The people had their own narrative, born from the womb of experience. From moments of fear and victory, and the sincere heroism experienced by ordinary soldiers on the front lines.

In many Egyptian homes, there is a story preserved and told on every national occasion about a relative or ancestor who participated in the war. Either as a fighter or as a member of the rear support. These stories are often characterized by a moving popular tone, combining pride and emotion. Some tell of a comrade who did not hesitate to sacrifice himself to save his battalion, or of the moment when the flag was raised under a hail of bullets, or even of the suffering in the desert moments before the crossing. Over time, these stories become something like family documents that are recounted with reverence, embodying the meanings of courage, sacrifice, and dignity.

Folk tales about the war

Folk tales that are not officially documented but live on in the collective memory have also spread among the people. Such as the story of the soldier who miraculously crossed the canal, or the simple farmer who left his land and joined the front on the day of the crossing.

Although some of these stories may have been exaggerated or embellished, they confirm one thing: that the October victory was a victory for an entire people who participated in it with their spirit, and perhaps with their words, or with the stories they passed on to the next generation.

In this report, we attempt to shed light on these stories, which form another facet of the memory of victory, among generations, some of whom lived through the war and others who heard about it from their grandparents, so that it remains alive in the popular consciousness to this day.

Allah Akbar… The cry of victory

Engy recounts stories about her father, Sari Salim Matias, an artillery soldier who participated in the October War, through stories she has kept since childhood. She was about six years old when she asked him one day about an old injury to his foot, and he told her that it was from the battle of the crossing in 1973.

She says that what stuck in her mind most from her father’s story was his constant repetition of the phrase “Allahu Akbar,” which he insisted was said in unison by Muslims and Christians alike. It seemed to him as if the mountains shook around them when it was said. She adds: “My brother and I used to watch war scenes in movies. Whenever we heard the cry of Allahu Akbar, we would jump for joy and repeat it as if we were crossing with them. My father said that at that time, they felt that every house in Egypt was repeating the same words with them.”

Despite the simplicity of these memories, they gave the children a vivid picture of how the soldiers lived those moments and how they carried them with them to their homes after the war, transforming them from field events into part of the family’s inherited legacy.

The “Abu Jamous” shell

Engy also recounts some of the stories her father told her after watching nationalist films. Such as the scene of his comrades being martyred before his eyes, and how some soldiers were miraculously saved.

In another incident, he said that an Israeli plane attacked him, and his commander ordered him to retreat. But he was unable to return, so he was forced to jump and run until he saved himself. After four hours, he returned to the battalion in torn clothes, to the astonishment of his colleagues and the battalion commander, who had been searching for his remains in the war corridors. He says he never looked back, but kept running without stopping until he was safe.

Engy also refers to another incident at a site where a missile known as “Abu Jamus” was used. Her father was an artilleryman at the time. He received instructions from his commander to identify the target, who told him: “Before I tell you to shoot, you will have already shot.” Indeed, the hero Sari Salim successfully carried out the strike without seeing the target directly. Only through the description, he hit the target with his first shot. Amidst the praise of his commander, who said audibly to the battalion: “God bless you, you got it, Sari did it on the first try.

She adds that the impact of the war remained with her father for many years, to the point that he would become confused and afraid of the sound of airplanes, even decades after the war ended. ”Even if a civilian plane flew over the building, he would tremble,” she says.

Despite the end of the war, the friendships between him and his comrades in the service continued. One of them, named Hussein, made sure to visit him regularly, even though he was from Mansoura, just to reminisce together about the war, which had shaped an important part of their personalities and lives after their return. Their stories became part of the family’s lasting memory.

Unofficial announcement of martyrdom

Batoul Salah tells the story of her uncle, martyr Shaaban Abdel Aal Mohamed, who was martyred on October 21, 1973, in Sinai. She says that the family did not receive official news of his martyrdom at first. This prompted her mother to search for him for a long time until she learned his fate.

According to what the family heard from the martyr’s colleagues, he managed to destroy several Israeli tanks. His commander then asked him to withdraw to preserve the position. But he refused to protect the battalion and the soldiers with him, which led to him being targeted by a missile that hit him in the head and led to his martyrdom.

Batoul recounts that her mother tried to confirm the news by asking his colleagues and going to the relevant authorities. She was eventually able to visit the martyrs’ cemetery, where she saw his body in his military uniform inside a bag, which confirmed his death. Among the details preserved by the family is that the martyr gave his colleague his badge and wallet before his death. He asked him to give them only to his sister, and the family still keeps this story as part of their private memory of the war.

Studying while fighting

Writer and critic Ahmed Karim Bilal recounts that his father, one of the soldiers who participated in the War of Attrition and lived through the prelude to the October War, studied while fighting. The war did not prevent him from completing his studies.

Ahmed says: “I was at the beginning of my journey toward obtaining a master’s degree in Arabic literature in 2003. I had many professional commitments that prevented me from studying, and one of my father’s friends always asked me about my studies. When I told him that work was preventing me from studying, he said to me, ‘My brother, your father used to study while he was fighting! He discovered that this was a trait his father had always been known for during the war and had become part of his legacy.

Returning to his father’s biography, he explains that he enrolled in the Arabic Language Faculty at Al-Azhar University in 1964. He was 26 years old, after a long break from education. Because of his age, his excuses for postponement were not accepted when he was called up for military service after the 1967 defeat. He was forced to perform his military service while still a university student. He was unable to take most of his exams during that period because they coincided with the war, but he continued his attempts later until he completed his university studies.

From family memories

In this context, the writer Amr El-Gendy recalls a part of his father’s biography, one of the participants in the war, who joined the military after graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture, and whose rank was most likely a reserve lieutenant in the artillery.

Amr says, “My father died when I was a teenager, which meant I didn’t have the opportunity to ask him detailed questions about his participation in the war or his experience of the epic crossing, but I remember well how proud he always was of his role in the October victory and how proud he was to have been part of this historic event. This pride became more evident every year as the anniversary of the victory approached, especially during the national operettas and songs that were broadcast on that occasion. He would follow them eagerly and sing along with obvious enthusiasm.” He adds that he still draws inspiration from those memories to this day.

Proud of the victory until his death

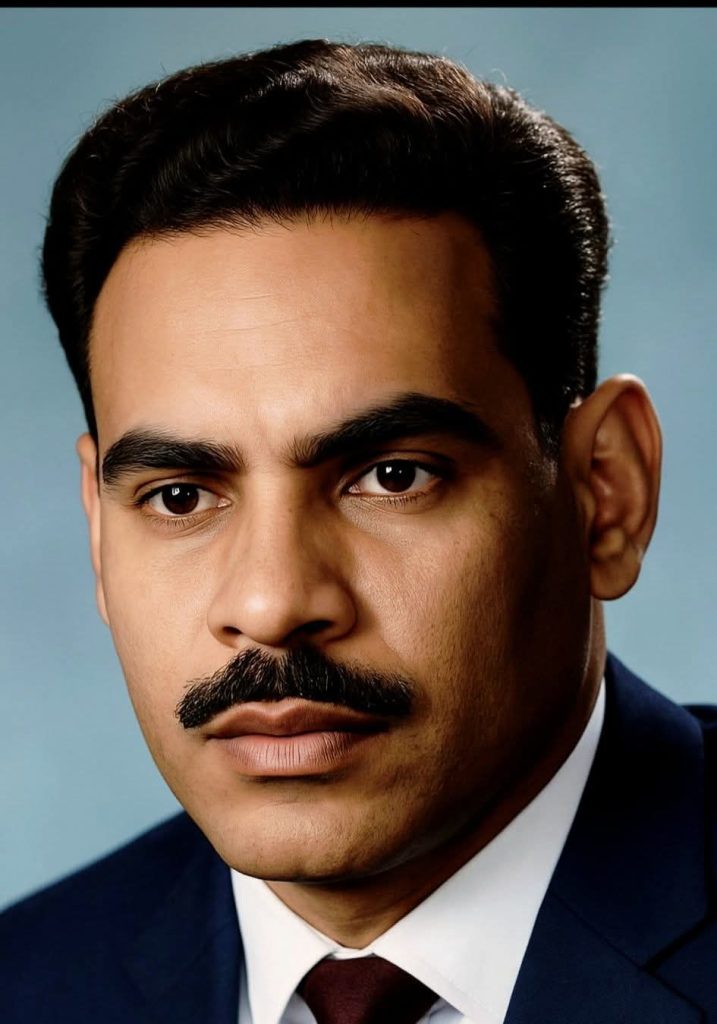

Helana Maher talks about her father, Corporal Maher Shafiq Hanna, from the Sharqia Governorate, who served in the Egyptian Armed Forces during the October War. He joined the army during the setback, replacing his older brother who was on a work mission abroad. Despite his young age at the time, he took full responsibility. He joined the army at a sensitive time in the country’s history.

She says that her father did not keep many photos from his service, except for a single photo that remained after most of them were lost. She adds: “My father was generous with his stories about the war; he made them part of our childhood. I was very proud of the October victory. I used to say to him, ‘I wish the war would come back again’—I was young and didn’t understand the meaning of war—and he would reply calmly, ‘War is not a good thing. I hope it never happens again.’”

The hero of Taba al-Shajara

One of the situations he often repeated in his conversations with us was the days before the war in the desert. Food was scarce, and soldiers sometimes hunted snakes and ate them to survive.

He was also deeply affected by the loss of his close comrades. He would see them laughing, and then suddenly a shell would fall on them, and one of them would be killed. As for the enthusiasm and faith that filled the soldiers’ hearts, Helena says: “He always told us that it was God who gave them the strength to carry heavy weapons and take them to the Bar-Lev Line. He was one of those who participated in the liberation of Taba al-Shajara.”

Taba al-Shajara, which was one of the most prominent Israeli enemy positions east of the canal, remained close to her father’s heart throughout his life, and he took his family to visit the site every year. He would explain to them the weapons used by the Egyptian side and those captured from the enemy. She adds that these memories were part of her early national consciousness. Her father’s stories were not just tales, but a true oral documentation of a battle he had lived through and participated in. They remained engraved in his memory until his death.

The first military statement… an unforgettable moment

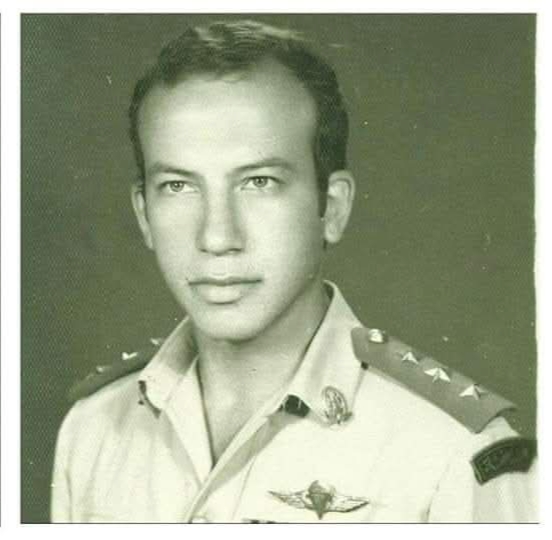

The stories of victory are endless, no matter how many accounts there are and how they differ from one household to another, but eyewitness testimonies remain the most influential. As part of documenting the testimonies of those who participated in the war as part of Egyptian heritage, we review the testimony of Major General Tarek Rajab, who spoke about the experience from the heart of the event. He spent seven years between training and waiting after the June 1967 setback. Then came the day of the crossing that an entire generation of Egyptian youth had long dreamed of.

Despite the end of the war and the achievement of victory, Major General Tarek Ragab says that the October War is always linked in his memory to the first military statement on October 6. This refers to the moment when the start of the crossing was announced, which remains present in his memory to this day.

Stories that did not make it into drama

Regarding the pivotal moments that were not documented in artistic or literary works, the Major General pointed out that the group of 73 historians played an important role in this regard. They worked to document the stories of the real heroes of the armed forces on social media.

He also stressed the importance of continuing to document all testimonies about the war, whether official or popular, saying: “There are many heroes and martyrs from all branches of the armed forces. I will never forget the martyr Ibrahim Al-Rifai and my colleague in the batch, the martyr Jamal Azzam.”

Regarding the impact of patriotic songs during the war, he explained that the song “Allahu Akbar Bismillah” was one of the most influential songs. It was broadcast to boost the morale of the soldiers and had a real impact on the battlefield. He also spoke about the atmosphere of war inside Egyptian homes. He pointed out that communication with family members was not easy, but everyone was living in a state of anticipation, believing that victory would inevitably come.

A call for documentation

The major general concluded his speech by saying, “The October victory is no less significant than the expulsion of the Hyksos or the Tatars. It is a historic achievement no less important than any other victory in Egypt’s history. Today, in the age of artificial intelligence, the internet gives us a greater opportunity to immortalize and document the war, as American cinema did with World War II.”

He adds: “The October War is not a movie… it is an experience that thousands lived through, and I was one of those who participated in it and was awarded the Medal of Courage.”