Fatema Mohamed: Reading not only introduced me to heritage, but also brought me closer to it

Fatema aspires to be a tour guide who presents Egyptian heritage in a contemporary spirit, while at the same time opening up to the Far East by learning Indonesian, driven by her passion for the values and ethics of that culture. Her goal is to be a bridge between Egypt’s ancient heritage and Indonesian society, emphasizing that determination and knowledge can create excellence no matter what the challenges.

A journey with reading, heritage, and language

Her experience was not formed solely through books, but also on the ground, as she contributed to community service at the Museum of Islamic Art and the Royal Carriage Museum, where she came into contact with Egyptian heritage in a living, tangible way. This balance between reading and practical experience enriched her personality and gave her a comprehensive vision that weaves together the past and the present. Because passion is only complete when shared, Fatema launched her YouTube channel, “Fatema’s Stories,” to share her story with books and history, and to open a window through which the stories of Egyptian heritage can reach the hearts of those interested in Indonesian culture.

Her journey with the national project was not easy. In the third season, she was eliminated in the first round, but that experience was not a loss; rather, it was solid ground on which she built her knowledge. She read more deeply and interacted with multiple communities and cultures, which gave her confidence and maturity that were reflected before the judging panels in the fourth season. Today, Fatema stands as a witness to tell us in this interview how reading is not just a hobby, but a life project, and that Egyptian heritage still needs young voices to carry its message to the world, believing that culture knows no boundaries.

- What encouraged you to participate in the National Reading Project from the beginning?

Since high school, I have been inclined to read, but I stopped when I entered university because I was busy with its new world. Then I wanted to return to reading, but I couldn’t find the right motivation until I found the National Reading Project. I liked its organization, and the website was simple to register on and clearly showed the goal, which encouraged me to return to reading again.

- How did you feel when you were announced as the third-place winner? Did you expect it?

I was very happy, especially with the words spoken by the presenter, Ayman Al-Jarrah, and what the judging panel said about the top three places. It made me very happy. Winning was not out of the question for me, but I didn’t give myself any false hope beforehand. I would have been happy even if I had come in seventh place, but I didn’t rule out the possibility of coming in third. However, I didn’t want to convince myself of that so that I could remain open to any outcome.

- Did you have difficulty choosing books during the competition?

Yes, I had a lot of difficulty in the third season, and I think that was the reason I didn’t qualify, as most of the books were scientific, which reduced the variety. It is also difficult to discuss purely scientific books with the judging panel. But in the fourth season, I was better prepared, as I spent a year reading in various fields, and the free reading competition organized by the university coincided with the national project. The university selected five heritage books of high value, so I said to myself: if I succeed, that’s great, and if I don’t, I’ll include them in the national reading project.

Among them was Al-Imta’ wa Al-Muanasa, which seemed difficult at first, but I used YouTube recordings that I listened to on public transportation, then returned to reading it in the evening. With repetition, the words became familiar, which made it easier for me to read and summarize. The book is about 450 pages long, and I finished it in about a month and a half. It added a lot to my knowledge, despite the effort it took. As for the book Al-Shifa bi Ta’rif Huquq al-Mustafa, it was easier in terms of language but long, and it took time to read. However, this experience benefited me greatly in the project, influenced my blog, and opened doors to new ideas that I had not been exposed to before, as I read in nine different fields.

- Has your reading style changed since winning in terms of analysis and book selection?

The change did not begin after winning, but rather during the fourth season’s qualifiers. I felt immersed in the world of reading, judging, and matrix questions. The experience of judging in the Republic’s qualifiers was so enjoyable that I forgot about the results and immediately began preparing for the fifth season. I started dividing the fields, reading with the matrix questions in front of me, and making sure to learn about the writer’s biography and other works, as well as the main and secondary ideas. Before the results were announced, I had finished reading ten books that I intended to participate with in the fifth season. This preparation was more conscious and in-depth.

- If you were to give advice to a participant in the fifth season, what would you advise them to focus on?

To be interested in a variety of fields, and not to limit their reading to the book alone, but to surround themselves with the writer’s biography and background, what has been written about the writer and the book, and to fully understand their ideas. I would also advise them not to be afraid of the judging panel; it is there for discussion and learning, not for judgment.

- How did reading help you present heritage in a simpler and deeper way?

Reading not only helped me present heritage, but also introduced me to it in the first place. It allowed me to learn about Egyptian identity and Islamic heritage, and gave me a solid foundation on which to build my ideas and personality. I then began to express heritage through the ideas and awareness that reading had formed within me.

- What role can reading play in introducing tourists to Egyptian history?

Tour guides are told that they should never stop learning and reading. This is true, but reading should not be limited to history alone; it should include various fields such as psychology, sociology, and the cultures of different peoples. During my volunteer work at the Egyptian Museum, I noticed that tourists do not come for information alone, as this is available in books and they have often read about it beforehand. Rather, they come to discover the culture, customs, and religion, and they want to understand the role of historical information in society. This is where the tour guide plays a key role, so they must have encyclopedic knowledge, quick wit, and tact in responding to various questions. Therefore, reading is essential in history and other fields.

- Based on your experience, what archaeological site or museum do you feel is not receiving enough attention?

I see that the ministry focuses on prominent places of heritage and historical value, such as Al-Muizz Street, where we find some monuments being exploited and receiving attention and restoration, while others remain neglected and unexploited. There is a problem that archaeologists are currently facing, which is that any monument that has not been highlighted in restoration projects is not registered as an official monument, despite its value.

- How has your experience in museums helped you combine academic study with practical application?

The university does not provide us with practical training; museums are responsible for that. The university’s role is limited to nominating some outstanding students, and in my faculty, this support was not available, so we applied for training ourselves. The first training I received was at the Gayer-Anderson Museum in Sayeda Zeinab, and it was relatively simple. After that, I joined a training program at the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir, which was more intensive and difficult, but it added a lot to my knowledge. These experiences taught me the basics of dealing with tourists and exchanging ideas and discussions in different languages and cultures. This helped me combine the practical with the theoretical.

- What aspect of Egyptian heritage caught your attention the most during your studies in tourism guidance?

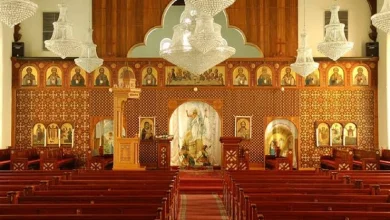

Islamic heritage, especially architecture. We have lost a large part of its value, as current buildings lack spirit or visual identity and do not provide comfort in the sense that Islamic architecture did. That architecture was a style that gave people breathing space, where they could sit even when they had no work to do, and unfortunately that no longer exists. It was also similar throughout the Islamic world, with only minor differences, and I hope it will return. In fact, my dream is to own a place designed in this style because of its aesthetics and artistry.

- Can current architecture be classified as heritage in the future?

No, because most of it lacks spirit and visual identity, and it exists all over the world. The exception is the engraved rural houses in some areas, designed in specific styles, which have a special character that could one day be classified as heritage, because they are distinctive and contemporary at the same time.

- Do you think cultural tourism in Egypt has received the attention it deserves?

It still needs to be developed. We have monuments and landmarks that speak for themselves, yet we focus on them and highlight them even though we have other sites that could be tourist attractions but have not been given enough attention. We focus on what markets itself naturally and neglect what needs to be marketed.

Artistic and cultural activities held in museums can also be an important attraction, as they create a connection between antiquities and art, but they are not carried out with sufficient quality or in a way that highlights their potential.

- During your experience at the Islamic Museum, what message did you feel Egyptian heritage was sending to the world? Did you notice that visitors needed a certain level of literacy to appreciate the exhibits?

This year in particular, I felt a sense of pride and dignity. Before working at the museum, I never imagined I would feel such a strong sense of belonging. Islamic history in Egypt is not limited to what people see today; it is much deeper and greater, and it is a fundamental link in the progress of all humanity. Therefore, it is important that the person presenting the information believes in it and is imbued with this awareness so that they can convey it sincerely. Our heritage sends messages about our identity and pride.

- Why did you choose Indonesian? Are there aspects of Egyptian culture that are related to Indonesian culture?

What unites us is Islam, which is an important factor that makes the similarities greater than we imagine. But their culture is different from ours; we are a Middle Eastern people in Africa, and they are a South Asian people. When I started working at the Museum of Islamic Art, I was going through a period of intellectual confusion, and I began to interact with foreigners and engage in discussions that left me torn between two extremes. At the same time, I had the opportunity to participate in a free reading competition, and the books were different from my way of thinking, so it was a challenge.

Later, when I came into contact with Indonesians, I found that their society, although Islamic, suffers from problems that are completely different from ours. This made me feel at peace, because we see ourselves as the source of Islam, while there are non-Arab Muslim societies that we do not pay attention to, and we focus only on the West. But the comparison between two Muslim societies with different cultural backgrounds highlighted to me the fundamental cultural and societal differences between us, despite our connection to one religion.

- If you had the opportunity to present Egyptian culture in Indonesia, what elements would you choose to represent Egypt?

If the presentation was aimed at Muslims and religious institutions, I would focus on Egypt’s Islamic heritage, Al-Azhar, and its scholars.

If it were aimed at other groups, I would showcase traditional folk arts, such as fashion, because of their diversity. Egypt is characterized by a wide variety of arts, and although Indonesia also has great diversity, it is not as rich. Therefore, it would be wonderful to showcase our culture with its distinctive character.

- How can you use what you have gained from the National Reading Project in your journey to learn Indonesian and build a dual cultural discourse that links Egyptian heritage and Indonesian reading awareness?

One of my dreams is for Arabic and Indonesian to be translated directly from one to the other without the intermediary of English. Indonesians, many of whom are Muslims, study Islamic law and Arab history, but their reliance on English causes many problems. They deserve to have translations directly from Arabic. Cultural discourse is embodied here, first in translation, and second in highlighting non-Arabic-speaking Muslim communities, so that we do not limit our view to the West alone as a model. Other Islamic communities reflect different values and experiences, and their perspectives contribute to the formation of a broader awareness.

Third, there must be mutual awareness between the two cultures, especially since some perceptions in Indonesian society need to be corrected, as they sometimes view us from a perspective similar to that of the West, while we hardly pay attention to them. Therefore, building a direct cultural bridge between the two countries is very important.

- The national reading project relies on critical analysis and the ability to derive meaning from texts, while tourist guidance is based on reading civilization through monuments and visual symbols. How can I use the critical reading tools I have acquired to formulate a guiding discourse that makes tourists read Egyptian heritage with both their hearts and minds?

This requires that the tour guide have absorbed the culture they are dealing with and understand the way its people think, so that they can present their country’s history, heritage, or culture in a way that arouses the visitor’s interest and reaches them deeply.

- If you had the opportunity to establish an initiative, would it be related to reading, tour guiding, Indonesian culture, or a combination of all three?

It would be related to reading. I already had an idea for a project in this regard, but it was never completed.

As for guiding, it has become frequently directed at Egyptians, with both good and bad aspects, while if it were directed at tourists, it would be closer to professional work than to an initiative.

As for Indonesian culture, it belongs to a society with its own characteristics, and I don’t think I can be a pioneer in it, although I may have a say in it. If the initiative is aimed at Egyptians, I can’t think of a specific project because the field is so broad.

Therefore, I think reading is the most appropriate. I have proposed an initiative based on organizing workshops for women and children next to archaeological sites, where a specific book is chosen and explained in three lectures, in parallel with workshops for children. This initiative would be held monthly at a different archaeological site, combining reading, culture, and heritage.