The experience of reenacting aspects of Egyptian civilization was incredible.

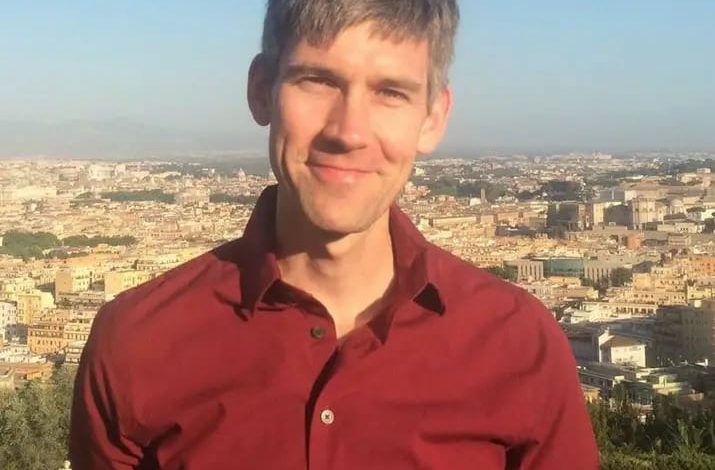

In a world where history is often reduced to books and museums, Sam Kean chooses to brush off the dust and breathe life back into the past. Through his book Dinner with King Tut, he takes us on a unique journey through time—one in which history is not merely documented, but felt and lived through the daily experiences of ancient people.

The book is an adventure that blends science and imagination, archaeological precision and the allure of storytelling. Through the lens of experimental archaeology, Kean does not simply observe the past from a distance; he immerses himself in its intimate details. What did ancient people eat? How did they craft their tools? How did they suffer, think, and dream? For Kean, imagination is not a luxury detached from truth—it is a bridge that connects us to our ancestors, shares in their emotions, and transforms history from static facts into a vivid human experience.

Ancient Egypt, with its mysterious past, silent mummies, and pyramids that continue to puzzle scholars, held a special place in his journey. He did not visit Egypt merely as an archaeologist, but as someone driven by a deeper question: where does history end and humanity begin?

In this interview, we accompany Sam Kean on that journey—and ask how a golden pharaoh transformed from a museum icon into a dinner guest, and how history itself can be retold from the inside out.

What initially motivated you to write this book? And why did you choose experimental archaeology as your entry point for telling history?

I love the big-picture idea that archaeology can answer about who humans beings are and where we came from, but the day-to-day work seemed so dull! Just people sitting around in the dirt for hours, brushing off little bits of pots. In contrast, experimental archaeology is far more lively and sensory-rich, because you’re making and doing things.

Your previous works have been entirely nonfiction. What pushed you to break that pattern and blend fiction with fact in this project?

I wanted the chapters to be as immersive as possible. You’re living a day in the life of someone from a specific time and place in human history, and fiction allows the reader to slip into that mindset even more fully.

Do you believe that using imagination to fill in the gaps in archaeological knowledge can sometimes feel more truthful than strict academic neutrality?

I don’t think they’re opposed to each other. Learning more about the history and reality of a place will only stimulate the imagination!

Were you ever concerned that readers might confuse what is documented with what is imagined?

No, because all the fiction is based on solid, authentic archaeology (as mentioned in the introduction), and there are clear section breaks between the fiction and nonfiction.

When a researcher physically reenacts the past, do you think they come closer to the truth than a historian relying solely on written records—or do both approaches complement each other?

The latter – they complement each other. We’ve learned a ton from traditional “dirt archaeology”, but it has its limits. Experimental archaeology can answer longstanding questions and stimulate new questions as well.

You note that each chapter reconstructs a single day in the life of an individual from the ancient world. What criteria guided your selection of these specific days and figures?

Partly my interest – what areas looked fascinating to me – and partly what place archaeologists were actively running experiments.

Of all the experiences you undertook, which was the most physically challenging—and which affected you most deeply on a psychological level?

Brain-tanning a deer hide and performing the ancient surgery were the most exhausting. And those affected me the most psychologically as well, because I wanted to quit so badly. But the frustration and anger – the emotions – were an important part of the learning process.

Why did you choose “King Tut” as the title of the book, even though the chapter about him focuses more on mummies and tomb looting than on his personal life?

It just sounded catchy. I thought readers would find it intriguing, which is what a title should aim for.

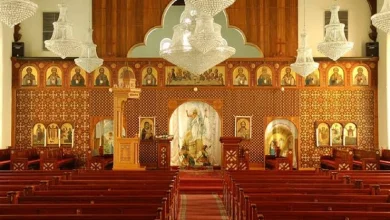

How was your experience of reimagining or physically reenacting life in ancient Egypt? Did you visit Egypt in person while preparing the book?

I have been to Egypt before. And reenacting aspects of Egyptian life was incredible – it was one of the places that I knew I wanted to write about from the very start. What I found especially fascinating was that we know very little about how mummies were made and especially about how the pyramids were built. These are two of the most iconic features of ancient Egypt, and they’re largely mysterious.

Getting to explore those topics was quite fun.

What might an American reader discover about ancient Egypt from the section devoted to it? And did writing this book challenge any stereotypes you personally held about Egypt?

I wasn’t aware of the big mysteries that remained about Egypt (i.e., about mummies and pyramids). I also think most Americans probably think the pyramids were built over a much longer timespan, instead of being concentrated in time. I also didn’t appreciate how much Egypt influenced the Greeks and Romans, and how many aspects of Egyptian culture were borrowed and transformed by those cultures.

In your book, you reference certain limitations in older theories regarding pyramid construction. Could you elaborate on what specific shortcomings you were referring to?

Most people think the pyramids were built by slaves, which isn’t true.

There’s also a general notion, even among some archaeologists, that the workers moved blocks on log rollers up ramps. But experimental archaeology casts serious doubt on those notions.

The book points to Africa 75,000 years ago as a starting point for human civilization—a choice that raises questions about African centrality in historical narratives. Was this a deliberate move to rethink the origins of civilization, or simply based on the findings of experimental archaeology?

Less the start of human civilization – that is, cities with agriculture, division of labor, a strong central state government, etc. I’d say it’s more the start of human life and human culture. But there’s no serious scholar out there who doesn’t think that human life, language, etc., started anywhere but Africa.

Have you received responses from non-English-speaking readers? And is translating the book into other languages part of your plan to reach audiences in the regions you explored?

Dinner with King Tut hasn’t been translated into other languages yet, so less so with that book. But it is being translated, yes. And with other books, I hear from readers all over the world on a regular basis.