Unlocking Cairo’s Hidden Gem: Why New Heliopolis Belongs on Egypt’s Tourism Map

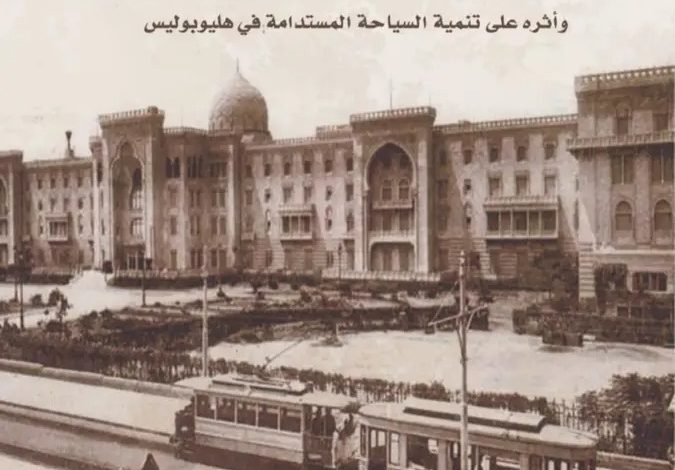

Heritage is more than old buildings; it is the story of a society, the identity of a nation, and the memory of a city. In her book, “Untapped Cultural Heritage and Its Impact on Sustainable Tourism Development in Heliopolis,” Dr. Basma Selim shines a light on one of Cairo’s rarest urban gems: New Heliopolis. As the director of the Baron Empain Palace and a doctoral researcher in heritage and museum studies, Dr. Selim not only documents the history of this unique district but also reveals the missed opportunities to revive its heritage for cultural development. In this interview, we discuss the challenges of preserving identity amid urban change and the potential for transforming heritage into a living resource for future generations

The book not only documents the history of the place, but also reveals the missed opportunities to revive this heritage and utilize it for cultural development. Its pages reflect the author’s expertise as a specialist in archaeology and heritage management, offering a critical perspective that calls for a rethinking of our relationship with our past and how to invest in it to shape the future.

In this interview, we open the file on Heliopolis as a symbol of untapped heritage and discuss with the writer the challenges of preserving identity amid rapid urban change and the opportunities for transforming heritage into a living resource that contributes to shaping the consciousness of future generations.

- Why did you choose the topic of untapped cultural heritage specifically as the focus of the book?

The book was originally my master’s thesis, which I completed in 2017 at the Sorbonne University in Paris. During that period, I was working as an archaeologist at the Baron Palace, and I conducted several studies on the palace itself and New Heliopolis. Through my work at the palace, I learned about its founder, and it pained me greatly to see the ruins and heritage buildings go unused, despite their great artistic and historical value.

I dreamed of linking Egyptian heritage with New Heliopolis through transit tourism, given the proximity of some of its archaeological and heritage sites to the airport. I used to travel a lot, and during transit periods I would make sure to explore nearby places. However, time constraints often prevented me from doing so.

As for the New Heliopolis neighborhood, I always felt that it was underutilized despite its enormous potential in terms of cultural heritage. Tourism usually focuses on major monuments, such as the pyramids or ancient archaeological sites in general, and even Islamic monuments. Meanwhile, Egypt’s modern heritage is neglected. I used to compare this with what I saw on my trips to Paris or Germany, where modern heritage is widely promoted. Many buildings and palaces are repurposed for tourism. This disparity is what prompted me to research the topic of untapped heritage.

- What is your vision for the exploitation of cultural heritage in Egypt?

What distinguishes Egypt most is that it has unique monuments and a unique Egyptology, which should naturally be a major focus for tourism. But at the same time, we should not overlook other heritage treasures, especially modern heritage, for which conferences and treaties have been held. The aim was to exploit and promote it and put it on the tourist map.

This is where my vision came from when I was preparing my master’s thesis, namely the need to focus on heritage cities such as New Heliopolis, Downtown, Maadi, and Zamalek. Many of their buildings are listed by the Cultural Coordination Authority (heritage buildings with a distinctive style).

New Heliopolis possesses what we call urban heritage. This is a type of heritage that has a unique character that attracts different types of tourism, given the unique architectural and cultural systems of these areas. We therefore need to direct domestic and foreign tourism towards these areas. This is to emphasize that Egypt is not limited to ancient, Greek, Roman, or Islamic monuments. It also has a modern heritage, rich in cultural and architectural momentum.

***

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a major architectural boom. Global architectural development began to take new paths, such as the Art Deco and Art Nouveau styles. Egypt had its fair share of this. Many Egyptian and foreign architects—Italians, French, and others—came to leave their mark. This made Egypt rich in diverse architectural styles.

It is also important to highlight this period and emphasize how Egypt, at one point, opened its doors to the world. It welcomed architects of various nationalities to imprint their countries’ spirit on its buildings. New Heliopolis is a unique example of a multicultural cosmopolitan city. It is one of the rarest heritage neighborhoods in Egypt that bears this distinctive international character.

- Is the absence of archaeologists from decision-making circles one of the reasons for the underutilization of cultural heritage in Egypt?

On the contrary, we as archaeologists are not absent from decision-making circles at all. In fact, we always strive to be present and active, and we are not alone in this.

This is the main point addressed by the book, which explores the role of stakeholders in the issue of underutilization. The idea is that we were present, but each party was working independently. This is what I noticed while preparing the letter, but now the situation has changed for the better. A clearer vision has begun to take shape, based on bringing together all stakeholders from different parties. The aim is to come up with an integrated project that takes all points of view into account, so that there is no disagreement or exclusion of any particular party. This is what is currently happening in Egypt in a remarkable way.

However, when I was writing the letter, there was a clear lack of coordination between the parties. There was no real cooperation to launch projects collectively at the implementation stage. Now, the situation is different. As archaeologists and decision-makers, we are present at various levels of the sectors and are among the most important elements in the decision-making process.

The closest example of this is that, at the time the letter was being prepared, the Baron Palace and the Sultanah Malak Palace had not yet been restored. Now, however, the restoration work has been successfully completed. Each team played its part in ensuring that the unique heritage, cultural, and architectural features of these buildings were preserved.

- Does Heliopolis still retain its heritage identity, or have changes affected it?

The city of Heliopolis has indeed undergone major changes, which are discussed in the book. A number of heritage buildings have been demolished, and some streets have been widened. Squares have been demolished and abandoned their original function as public spaces to become streets. In addition, a large number of bridges have been built. I noted all these changes and added them while translating the book, as they did not exist at the time of writing.

Another notable difference is the removal of the metro line from New Heliopolis, which has clearly affected the character of the neighborhood. Despite these successive changes, New Heliopolis still retains much of its authenticity, with its distinctive architectural style and cultural fabric, which makes it different and unique from other neighborhoods.

- Can the different architectural styles in New Heliopolis be combined to highlight its heritage identity?

Indeed, this is what Baron Empain did when he founded New Heliopolis; he wanted it to have a distinctive Arab character that combined European style with Arab identity. This fusion was achieved with a unique harmony, resulting in what we know today as the Heliopolis style, which is unique in itself. It is currently studied as a special architectural style. It is characterized by the integration of Islamic civilization with European elements. In addition to some architectural features such as the boulevards in the Korba, all of which served the community at the time and attracted residents and visitors to the city.

What distinguishes Heliopolis is that it has a unique visual identity, which is rare. Many cities in the world do not have a visual identity, but rather create one to put themselves on the tourism map. In New Heliopolis, however, this identity already exists.

All that is missing is for stakeholders to work together to include it on the tourist map and open some closed places to the public. Such as the Basilica Church, which is one of the most important archaeological buildings in New Heliopolis. Especially since Baron Empain himself is buried there.

***

New Heliopolis is also characterized by unique architectural buildings such as the Jewish temple, which opens the door to the creation of various tourist attractions, including religious sites. This is especially true with the presence of old mosques such as the Sultan Hussein Kamel Mosque and the Hafiza al-Alfi Mosque, which reflect the return of architects of that era to revive the Mamluk style. The Ali Hassan Mosque alone has an architectural richness that deserves to be turned into a religious tourist attraction, similar to what exists in the Interfaith Complex.

Urban tourism can also be exploited in Heliopolis, through strolling through the streets of Korba and Granada, picnics, and restaurants. These are unique elements with a special identity that should be preserved and directed towards cultural heritage tourism, both internally and externally. Heliopolis can also be linked to its historical depth, stretching from Ain Shams and the Tree of Mary, as well as its modern historical extension.

- In your opinion, what distinguishes the architecture of New Heliopolis and how can tourism be directed towards it?

New Heliopolis is characterized by unprecedented architectural diversity, which has not been sufficiently studied or highlighted except by architecture specialists. It is important to direct tourism to this heritage, especially since the tourists who visited New Heliopolis during the preparation of my thesis expressed their fascination with its beauty and their desire to see places like this in Egypt, in addition to the pyramids and other well-known monuments. These visitors showed great interest in the modern heritage of the 19th century, with its houses and streets, and the Renaissance. In addition to the pyramids and other well-known monuments.

These visitors showed great interest in the modern heritage of the 19th century, in the houses and streets, and in the urban renaissance and architectural planning that characterizes New Heliopolis. This confirms that New Heliopolis is not just a residential neighborhood, but an open museum that reflects an important phase in the history of architecture and urban development in Egypt.

- What is the difference between archaeological documentation and the cultural utilization of heritage?

Documentation is a fundamental first step, while utilization comes later. For example, when we began to consider restoring the Baron Palace, the building was abandoned and in a state of serious disrepair. It was not possible to begin restoration immediately without first undertaking a documentation process. Documentation takes many forms, including photographic and architectural documentation, as well as the use of modern techniques such as laser scanning. Archaeological documentation also involves gathering all available information about the monument, which may not have been previously studied, so that this data can contribute to the restoration process later on.

Reuse is the next crucial stage, especially for unused buildings. It is always preferable to restore a building and then reuse it immediately, in accordance with internationally recognized standards. This ensures its preservation and sustainability. The new function of the building should be as close as possible to its original identity. For example, if the building was originally an Islamic agency built to serve as a hotel for merchants, repurposing it today as a hotel is a continuation of its historical identity.

By analogy, in order to preserve the identity and uniqueness of the Baron Empain Palace, the most appropriate use for it would be as a museum that tells the history of New Heliopolis and explains the nature, form, and origins of this neighborhood. This is what New Heliopolis really needed.

- What message did you want to convey in the book that was reflected in your vision?

When we graduate from the Faculty of Archaeology, we are called soldiers of archaeology or guardians of antiquities. As I am from a relatively old batch, there was no such thing as a heritage management major in our time. Today, it has become a core subject taught in archaeology faculties at all universities. We graduated with an understanding of the value of heritage, but we lacked knowledge of how to manage or repurpose it.

My master’s degree, which resulted in this book, made a big difference in how I view heritage and how to deal with it. For example, when I was an inspector at the Baron Empain Palace before my master’s degree, all my thinking was focused on how to restore and preserve the monument and open it to the public. After my master’s degree, I began to look at the issue from a different perspective, based on reusing the building to ensure its long-term sustainability and preservation.

***

This is the vision I sought to highlight in the book. The most important thing is not only to preserve the monument, but also to ensure its sustainability for us and for future generations. Sustainability has several mechanisms. Among them is that restoration should be environmentally friendly. It should also preserve the social and psychological activity associated with the place. This vision is not limited to Heliopolis alone, but can be applied to all of Egypt.

After finishing the letter, I said that if this vision were actually implemented, it would be suitable as a general strategy to be applied to all heritage neighborhoods in Egypt. In this way, we would create an integrated network of heritage neighborhoods included on the tourism map.