Filming in Egypt’s Oases: How the Desert Became a Natural Film Studio.

At dawn, before the city woke up, the camera moved slowly between the dunes in the New Valley Governorate. The sky was tinged with orange, and the sound of the wind was like a natural soundtrack. On top of a huge rock, a technician set up the lighting, while the director called out over the radio: “Ready for scene 12… Action.”

Read more: Filming in Egypt’s Oases: How the Desert Became a Natural Film Studio.At that moment, time stood still for a moment, and the desert of Al-Wahat transformed from a void into a vibrant painting, with the cameras capturing what words cannot describe. Bab Masr showcases the most important films and documentaries shot in the oases.

A history stretching back thousands of years

“Those who come here to film don’t see sand, they see a history stretching back thousands of years. They see that this place can tell a different story about Egypt, far from the hustle and bustle.” With these words, Islam Safari, a native of the Islamic village of Al-Qasr in Dakhla and a freelance tour guide, described the magic of the place.

He added with a smile, pointing to the palm trees behind him: “The oases have a visual charm that cannot be found anywhere else. I remember a foreign director once telling me: ‘The light here is unlike any other in the world.’”

Oases on the cinematic map

Since the late 1960s, Egyptian filmmakers have turned their cameras to the distant south to capture its distinctive atmosphere of isolation and contemplation, but the real breakthrough came with the series Wahet al-Ghoroub (Sunset Oasis 2017), much of which was filmed in the oases of Dakhla and Kharga.

This work was a turning point that brought the oases back to the forefront, not only as a filming location, but as a symbol of a lost Egyptian identity. Raafat Saad, a tour guide in Dakhla, says he witnessed the filming of some scenes of the series and describes the reactions of the locals, saying:

“People were amazed when they saw the images of the oases in the series, even though they live here. In scenes set in a mud house in the Islamic palace, people thought it was a studio set, but everything was real.”

He adds: “When the camera enters these houses, it reveals a simple and sincere beauty, conveying the feeling of the place as it is, without artificial embellishment.”

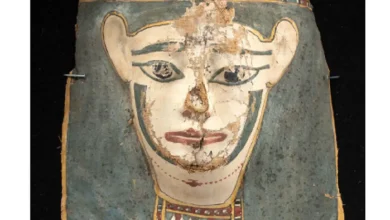

Human heritage at the heart of the shot

Inside the Islamic palace village of Dakhla, which dates back more than eight centuries, the mud walls still silently tell the stories of their ancestors. Numerous documentary cameras have wandered here, documenting the details of daily life: children in narrow alleys, women weaving wicker by hand, and the sounds of the call to prayer echoing between the ancient walls.

Souad Abdellatif, one of the women working in handicrafts at the palace, says: “Before the filming, we never imagined that anyone would be interested in us. When they started filming, tourism boomed, we started selling our products, and young people stayed in the country instead of traveling.” She adds: “The cinema made us feel like we were part of a bigger picture. And that our simple work has value.”

The camera as a tool for development

Filming in the oases is no longer just an aesthetic spectacle, but has taken on a clear economic and social dimension. Mohsen Abdel Moneim, director of the Egyptian Tourism Promotion Authority in the New Valley, says: “In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in requests for filming, both from Egyptian and foreign directors. This has contributed to the creation of job opportunities and increased income for the people of the region. As an authority, we are working to facilitate the procedures for filming and provide logistical support to encourage filming with the aim of promoting tourism in the New Valley.”

He continues: “When viewers see a place in a film or series, they become curious to visit it, and this is free publicity that puts the New Valley on the map of cultural and environmental tourism in Egypt.”

Cinema drives the market

Every time a camera is set up in the oases, the local markets come alive. Hotels fill up, restaurants are busy preparing meals for the film crews, and young people find temporary jobs as drivers, assistants, or even extras.

Islam Safari says with a laugh: “As soon as we know there’s filming, the whole country gets moving. Those who have camels rent them out, those who have cars transport equipment, and all of this creates real economic activity.”

Raafat Saad confirms: “People now see cinema as an opportunity not only for fame, but also for increased income. The camera doesn’t just film, it sows hope in the hearts of everyone here.”

Oases… the next natural studio

A project currently under discussion aims to create an open film shooting area in the New Valley, including infrastructure for film production and accommodation, turning the oases into a natural open studio.

Mohsen Abdel Moneim explains: “We proposed the project to the authority because, if implemented, it will transform the governorate into a center of attraction for Arab and foreign artistic production. We have a diverse landscape of mountains, oases, and temples that can be used to film any kind of work.”

He adds that the governorate has already begun collaborating with film academies in Cairo and Alexandria to organize training workshops for local youth on filming, directing, and editing. This is an attempt to make the local residents part of the industry, not just the backdrop in the picture.

“Arak Al-Balh” (Date Palm Sweat): Cinematic Scenes in the Heart of the Desert

The New Valley Governorate was not just a silent backdrop in Egyptian cinema, but a heroine speaking of beauty and serenity in works that shaped the consciousness of generations of viewers. In 1998, director Radwan Al-Kashif shot his famous film “Arak Al-Balakh” in the heart of the Islamic village of Al-Qasr in the Dakhla Oasis. The film depicts the life of a Bedouin community facing the transition between tradition and alienation.

Tour guide Raafat Saad, one of the residents of Dakhla who helped secure the filming location, says: “This film changed people’s perception of oases. At that time, the film crew lived among the locals for more than two months and saw for themselves that the desert here is not a void, but a complete life… palm trees, water, and people who love the place. Filming took about eight weeks, in temperatures exceeding 40 degrees Celsius. The crew used the old village houses as real filming locations without any decorations.“

Islam Safari recounts: ”To this day, the people of Balat still remember Sherihan and Abla Kamel walking through the streets of the village, as if the film had been made yesterday.”

White sand dunes… An ideal location

In 2005, director Ahmed Nader Galal chose to shoot some scenes from the film Abu Ali, starring Karim Abdel Aziz and Mona Zaki, in remote areas of the desert near the Farafra Oasis. The director took advantage of the white sand dunes, which gave the scenes a cinematic, international feel.

Abdel Moneim adds: “The film attracted a lot of attention because the scenes shot in the Islamic village of Al-Qasr in Dakhla made people and locals realize that the oases are an ideal location. Not only for Egyptian films, but also for international productions.”

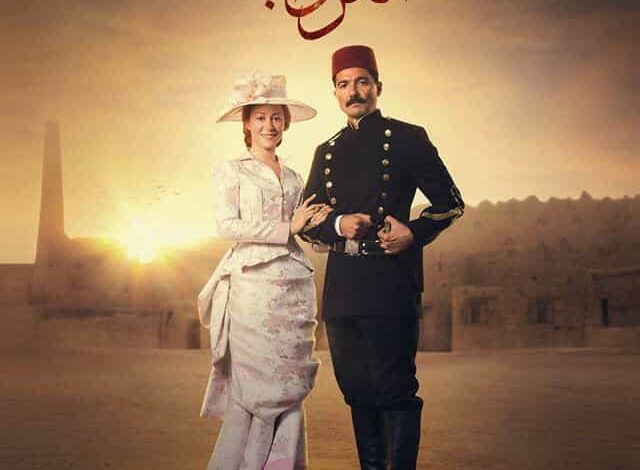

Filming is not just an art… it’s also an economy and tourism

Cameras were not limited to cinema alone; television dramas in the New Valley found a unique spirit unlike anywhere else. In 2017, the series Waha al-Ghoroub (Oasis of Sunset), based on the novel of the same name by the great writer Bahaa Taher, used the oasis environment to bring to life its historical story set at the end of the 19th century. Parts of the work were filmed in areas resembling ancient oases in terms of architecture and nature, giving the viewer a rare visual authenticity.

Mohsen Abdel Moneim confirms that after the series aired, the Egyptian Tourism Promotion Authority began preparing a map of locations suitable for filming in the oases. He adds, “Filming is not just an art, but also an economy and tourism. Every day of filming is a day of work for the people of the region… Cars, hotels, restaurants, and craftsmen. Thus, the New Valley desert has been transformed from a mere backdrop in the frame to a living element pulsating with heritage and human warmth. The oasis region has truly become the largest natural studio in Egypt. We await more cameras to capture its magic and bring it back to the world.”