the first dance theater performance to bring together children and the elderly in an artistic and humanitarian demonstration entitled “We Walk Together.”

On a warm evening in Luxor, the Bahaa Taher Cultural Palace was bustling with life in a different way. It was not a poetry evening, nor a traditional performance, but rather an unprecedented event in Upper Egypt: the first dance theater performance to bring together children and the elderly in an artistic and humanitarian demonstration entitled “We Walk Together.”

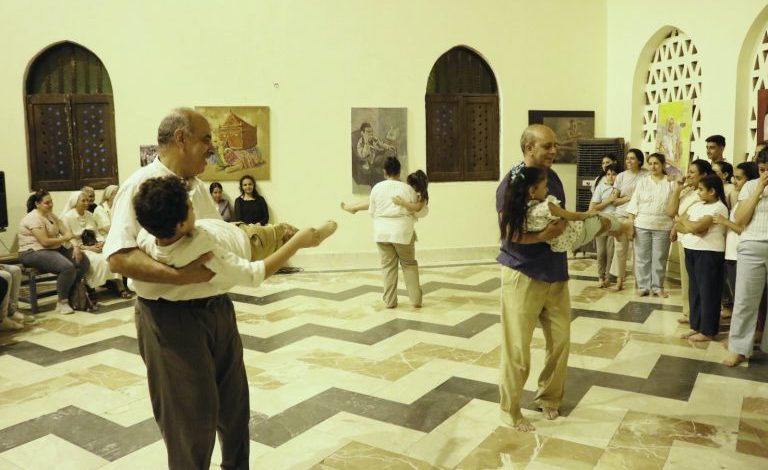

Thirty participants, including grandmothers and grandchildren, mothers and young girls, retired men and children in the prime of their lives, gathered on stage not only to dance, but to restore the forgotten idea of “human connection” through moving bodies, beating hearts, and expressive souls.

We Walk Together

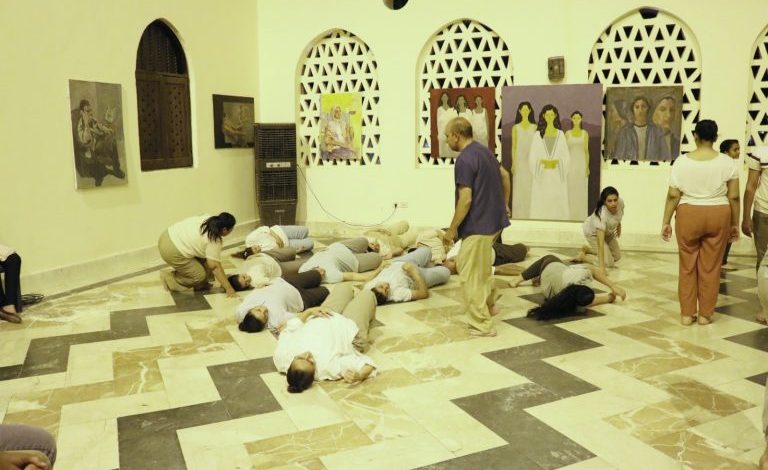

The work is the fruit of many months of training and workshops in the fields of contemporary dance, movement therapy, physical theater, and interactive games. It is part of the “We Walk Together” project, implemented by Eco Arts in collaboration with the Upper Egypt Association for Education and Development. With support from the European Union and the European Cultural Institutes Union.

The performance does not tell one story, but dozens of small stories that emerge from a moving body, from a hand embracing another hand, from an eye meeting another eye. No dialogue, no dramatic monologues, just movement, gestures, and shared steps. It is as if the show is saying: belonging begins with the body… with the ability to dance together, despite differences in age and experience.

Healing through the body… and the birth of a new feeling

Nermin Habib, director of the show Walking Together and co-founder of the company “Eco,” says: “The show ‘Walking Together’ was designed specifically for the elderly and children. We wanted to rediscover the innate body within each individual, to awaken the child in the elderly, and to give children a sense of identity and curiosity through art. In an increasingly isolated world, movement has become a means of resistance.”

Mario Michel Seha, the project’s co-director, explains that this work is a rare experience in Upper Egypt, as bringing generations together through the art of movement is not common. The contemporary dance and physical theater workshops were an opportunity for people to discover themselves through play, art, and beauty. “In the show, for example, an elderly man spontaneously danced with a 7-year-old girl. A moment like that alone is enough to change your outlook on life.”

“I used to think dancing was shameful!”

Karmina Hani, 17, from Luxor, speaks with eyes sparkling with enthusiasm: “I’ve been playing tahtib for four years, but I’ve never felt what I felt here. I used to think dancing was shameful for girls, something to be embarrassed about. But when I started contemporary dance, I understood that it is an art, not just physical exercise. It is a way for me to express feelings that I cannot put into words. At first, I was physically weak… Now my body is stronger. My self-confidence has increased, and I am in great shape. This art is therapeutic.”

Life begins after 60

On the other hand, Youssef Habib, a 60-year-old retiree, stands proudly in his performance clothes and says, “I am an artist by nature. I used to do artistic sketches. I loved the idea of dancing despite my age. When I first started training, I felt like a young man again. I participated in the show with a child who was playing with me and laughing, and I became a child again. This feeling of playing is important, especially in a time of screens and isolation. I believe that life begins after 60. This theater has proven to me that the body can dance, no matter how old you are.”

Not just dancing… But a journey

The project did not stop at the theatrical performance, but also included a short documentary film that recounts the participants’ journey and their personal experiences with the body and dance. In addition, there was an art exhibition in collaboration with the Retrospot Center, which brought together paintings and interactive works produced by the participants or expressing their feelings.

The show was well attended by the local audience and a number of people interested in community arts. It is scheduled to be presented again in Cairo soon, carrying a message from southern Egypt to anyone who thinks that art is a luxury or that the body cannot dance after a certain age.