The development of Ramses Square and the absence of the concept of “humanizing the city”

The Egyptian government is continuing what it calls the development of Ramses Square, one of the most vibrant squares in Cairo. Under this pretext, the historic Misr Station building and the Egyptian Railway Engineering Administration building, both dating back to 1910, have been demolished. This is part of a government plan to expand the 6th of October Bridge, build a new entrance to the area, and construct a shopping mall and multi-story parking garage. The project reveals the current government’s approach and its departure from the concept of “humanizing the city,” which was present in a global project to develop the square in 2009.

The government of Mostafa Madbouly and its current partners are proud of the project to develop the square overlooking the country’s main train station. Last June, Dr. Ibrahim Saber, governor of Cairo, stated that the goal is to restore the historical status of Ramses Square. However, he did not explain how this would be achieved by removing the historic buildings overlooking the square. It appears that the project the government has begun is merely an expansion of roads and bridges to accommodate more cars, contrary to development that emphasizes the concept of “humanizing the city,” where priority is given to the comfort of citizens by providing green spaces.

***

The term “humanizing the city” is no longer a luxury or words uttered by intellectuals or specialists. but rather an important philosophy that explicitly states that city dwellers have the right to enjoy their city through the provision of free green spaces and open areas, to make the city more suitable and comfortable for people, by improving infrastructure and increasing green spaces, thereby encouraging movement and a culture of walking in a people-friendly social and environmental setting.

Here we quote the definition of the Madinah Development Authority in Saudi Arabia and its program for the humanization of Madinah, a project that is currently underway. The idea of humanization is defined as “the creation and affirmation of the human dimension in the urban development and growth of all segments of society, by improving visual identity, supporting and encouraging cultural, promotional and artistic programs, and establishing urban squares, open areas and green spaces.”

Surprisingly, this was the logic adopted by the Egyptian government in 2009, so what happened this year?Going back in time, we discover that in 2008, Ahmed Nazif’s government decided to organize an international competition to develop Ramses Square through the Cairo Governorate and the National Organization for Urban Harmony. A total of 101 contestants from 38 countries around the world submitted proposals for the development of the square, including 29 Egyptian consultants.

***

Thirty-four project proposals were submitted and reviewed to select the winning entries. Dr. Abdel Azim Wazir, then governor of Cairo, offered a prize of $100,000 for the winner of the square development competition and $75,000 for the runner-up. and the third place winner would receive a prize of $50,000.

The jury that discussed the submitted projects was chaired by Dr. Abdullah Abdul Aziz, Professor of Architecture and Planning at Ain Shams University, and included Professors Abdul Mohsen Barada and Samah Al-Alaili from Egypt, Alexander Beldiman from Romania representing the International Union of Architects, Diana Agrist from the United States, Axel Schultz from Germany, and Eliso Arredondo from Mexico.

***

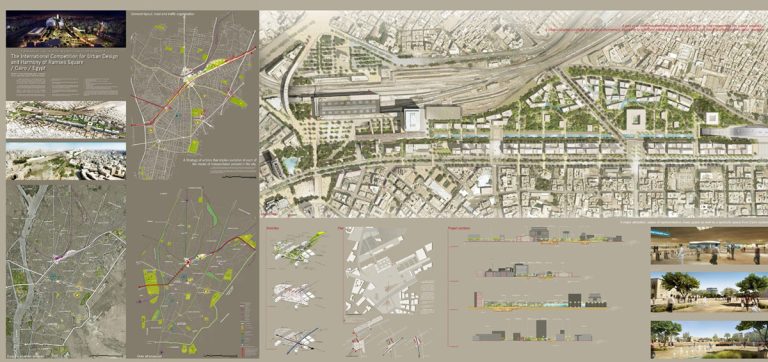

In mid-September 2009, the French group Arep, in partnership with the Egyptian firm Bect, represented in Egypt by Dr. Omar El-Husseini, Professor of Urban Design and Planning at Ain Shams University, was announced as the winner of the first prize in the international competition for the redevelopment, urban design and cultural coordination of Ramses Square, worth $100,000.

The prize, worth $100,000, was awarded for the first prize in the international competition for the redevelopment, urban design and cultural coordination of Ramses Square. The Irish firm Ouilligan Architects won the second prize, while the Turkish group Nimat Aydin came in third place.

The winning projects agreed on the need to remove the October Bridge in the square area by finding alternatives to it. The winning project includes removing the bridge and constructing a tunnel in the area between the ambulance station and Ghamra, with a record increase in green spaces (18 acres), and removing all iron barriers in the square, with the square being designated for pedestrian walkways and the preservation of heritage buildings, including the Misr Station Market building and the Railway Engineering Administration building. However, the project was never implemented, as many things happened within the corridors of government that disrupted the project and caused it to quickly falter.

***

It seems that the person primarily responsible for the project’s failure is not the January revolution, as some claim, but rather Dr. Mostafa Madbouly, who was head of the Urban Planning Authority at the time. In a report published by Al-Shorouk on May 20, 2011, we find statements by Samir Gharib, head of the Urban Coordination Agency at the time, who openly states that he asked Ahmed Nazif before the revolution to implement the project that won first prize for the development of Ramses Square. “However, he was surprised when Mustafa Madbouli, head of the Urban Planning Authority, presented another project, given that the cost of constructing a tunnel in Ramses Square had reached one billion pounds. and due to the difficulty of implementing it, Madbouly proposed another project despite the existence of a solution to what was described during the meeting as a difficulty in implementation, which was to adopt the proposal of the second prize winner to move the October Bridge away from Ramses Square.”

Samir Gharib recounted the events that led to the suspension of the project to develop Ramses, Al-Ataba and Al-Khazindar squares at a seminar held under the title “Activating the National Agency for Cultural Coordination Competitions,” in cooperation with the Architecture Committee of the Supreme Council of Culture in May 2011, saying that in 2010, the Cultural Coordination Agency sought to implement the winning projects in the international competition on the ground, but no one responded. After the Ramses competition ended, he sent a letter to the Council of Ministers requesting the implementation of the winning project, but received no response for a whole year. He was then invited to attend a meeting chaired by then Prime Minister Dr. Ahmed Nazif to discuss the winning projects in the Ramses competition.

***

Samir Gharib was surprised to find that the meeting was not to discuss the implementation of any of these projects, but rather to assign Ahmed Nazif to the head of the Urban Planning Authority, Mustafa Madbouli, to develop Ramses Square.

He was accompanied by professors from the Faculty of Engineering at Ain Shams University, who objected to the implementation of the competition project on the grounds that it was not possible to convert the October Bridge into an underground tunnel due to the presence of the subway. Gharib added that he suggested combining the three projects and taking the best of each, but his suggestion was rejected, leading Gharib to accuse them of wasting public money, as the cabinet itself had allocated $2.5 million for an international competition for Ramses Square, only to ignore the results.

***

It seems that Madbouly’s insistence on pushing through his project led to the award-winning project in the international competition being shelved, and it only appeared in the news from time to time.

In December 2013, talk of the project resurfaced when Dr. Hazem El-Beblawi, then Prime Minister, ordered the formation of a committee comprising the ministers of transport, housing and culture to develop a final plan for the development of Ramses Square. Dr. Galal Saeed, then Governor of Cairo, stated that his meeting with urban planning officials had concluded with approval to activate the planning studies for the square, which had been prepared since 2009. Dr. Samir Gharib said that the proposed planning features were the result of an international competition for the planning of the square, and it was decided to submit these studies to the prime minister in preparation for the project’s implementation.

The project was then shelved again, but in May 2016, Al-Ahram newspaper conducted an interview with Dr. Omar Al-Husseini, who was then head of the urban planning department at Ain Shams University. The interview focused on the fate of the project, in which he participated and won first prize for the development of Ramses Square. He revealed that the project had been halted due to the January 2011 revolution and spoke of the state’s desire to start implementing the stalled project, pointing out that “it is a national project that will have a significant return on investment and achieve many objectives in terms of traffic, aesthetics and the environment.” However, it seems that this logic is no longer up for discussion in government projects at the moment.

***

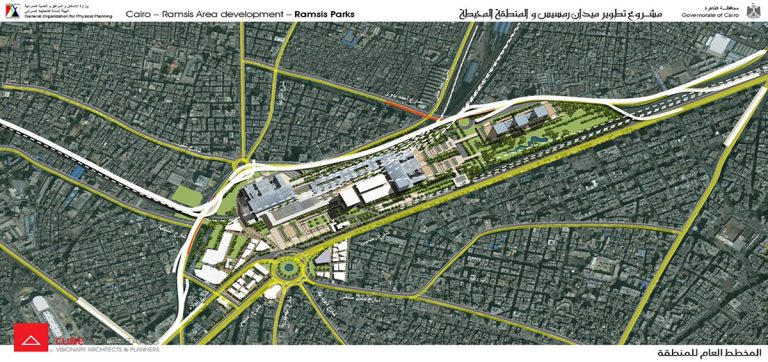

There are no clear indications as to the content of the alternative project proposed by Madbouly in 2010, but we can expect that the project in question is the one submitted by Cube Consultants, , an engineering and architectural consulting firm founded in 1990 by Prof. Ashraf Abdel Mohsen, professor of architecture at Cairo University. This is the company that developed the idea known as “Cairo 2025,” which impressed Madbouly at the time, before it was adopted by the government. The company has presented numerous development projects for Cairo, including the Ramses Square development project, which included not removing any heritage buildings in the area, moving the October Bridge to behind the Misr train station, and designing the Ramses recreational gardens in the area. However, even this plan, which Madbouly was enthusiastic about in 2010 and wanted to implement at the expense of the winning plans in the international competition for the development of the square, was not implemented!

Mustafa Madbouli became prime minister on June 7, 2018, and remains in office to this day, so it was not surprising that he turned his back on the winning projects in the international competition for the development of Ramses Square. What is surprising, however, is that he abandoned the alternative project he was enthusiastic about in 2010, only to surprise us with a new plan that is being implemented on the ground, on the corpse of our heritage, with the removal of historic buildings and the introduction of the concept of humanizing the city through the expansion of streets and bridges. There has been no mention of parks and open areas for pedestrians, nor of removing the iron fences that obstruct their movement. We are now faced with a new project that favors car owners, with the expansion of streets and the reduction of areas for picnics and walking. It sends us a message of insistence on the ugliness of the October Bridge, and even its expansion rather than its removal, and the exclusion of any aesthetic idea that respects the humanity of citizens whose rights are always violated.

***

The crisis revealed by the development of Ramses Square lies in the absence of planning that preserves the heritage environment in which it operates, especially in a place like the millennial city of Cairo, and in the absence of serious and genuine community dialogue and the centrality of the concepts of humanizing the city and the right of citizens to enjoy the spaces and areas within it. Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly is a man who has been familiar with the details of the square’s development since 2008, but he did not approve any of the winning designs in the 2009 international competition, not even the design submitted by Kube in 2010, which Madbouly himself had enthusiastically supported.

Instead, he suddenly imposed on everyone a plan that came out of nowhere, violating everything that had been agreed upon by the competing projects and Qub’s alternative project, which saw the necessity of moving the October Bridge away from Ramses Square, despite their differences in how to handle the relocation. The result is the implementation of a project that no one knows who proposed, which goes against logic and all the projects and plans that have been put forward, by working to expand the October Bridge, remove heritage buildings, exclude the idea of public parks, and keep the iron fences that make the square feel like a large prison!