Sonallah Ibrahim answers the question: How do I write?

It is not easy for a writer to talk about his experience, because when he does, it is like cutting his way through a forest of tangled branches, which requires effort and skill to untangle, not to mention determining where to start.

Perhaps the external factors that influenced the writer’s career are the best introduction to this discussion. They are less difficult to address and are usually shared by a number of writers, or even an entire generation. I was not alone in becoming aware of the turmoil of the early 1950s and witnessing the birth of a new realist movement in poetry, fiction, painting, sculpture, and music.

Here was a young bourgeoisie seizing power through the army and engaging in a bitter struggle against colonialism and feudalism. Here was Mahmoud Amin al-Alam, alongside Abdel-Azim Anis, fighting the famous battle against Taha Hussein and Al-Aqqad in defense of the social significance of art and literature and of the unity of form and content in artistic work. Youssef Idris wrote his first stories in a modern language that did not shy away from colloquialisms, depicting, along with Al-Sharqawi, real rural life rather than a cinematic version of it. Ihsan Abdel Quddous exposed the hypocrisy of prevailing morals through his modern treatment of the relationship between men and women. And Naguib Mahfouz, after a difficult struggle with style and language, wrote his immortal trilogy.

***

But the new realism soon revealed its unrealistic face. The young bourgeoisie came forward with an ambitious national project for the future, based on national independence, unity, and development through industrialization and social justice.

It was natural that this massive revival would bring together a set of unique contradictions at different levels, some of which seemed highly confusing. Workers, for example, participated in the management of projects, while the police repression required by the fierce struggle against colonialism and reaction also affected those who dared to disagree or participate.

Little by little, reality appeared more complex than a mere song of struggle against colonialism and for the future. A state of alienation prevailed in society, and the new realism revealed a shallow romanticism that quickly lost its credibility and appeal.

There was a certain similarity between the alienation experienced by society and that experienced by the centers of Western modernity before it, due to different reasons related to the subjugation of man to the machine and the state, and the collapse of the old colonial empires. This crisis was reflected in Western novels, where the familiar chronological sequence was no longer useful for understanding reality, nor was the traditional plot. The traditional novel gave way to adventures based on Westernization and ambiguity, eschewing events, psychological characterization, and emotion.

***

The Arabic novel was bound to be influenced by these developments, given the new means of communication that were about to remove borders and restrictions, and given the similarities between the crisis here and the crisis there, and specifically between the results here and the results there, because we must never forget that our crisis is the product of a society moving towards industrialization, and the crisis there is the product of a society suffering from the results of industrialization.

Naguib Mahfouz began his experiments with the consciousness movement, multiple perspectives, and absurdity, giving rise to the phenomenon known as the “sixties generation.” It was in this atmosphere that I took my first steps in writing, with short stories that reflected various influences and an unusual interest in form and experimentation. I began a novel, which I soon abandoned when I realized how clearly it was influenced by Virginia Woolf. Then I started a realistic novel in a lyrical style, in the prevailing vein, perhaps influenced by Mahfouz’s trilogy, which I imbued with a mysterious atmosphere that evoked awe. I quickly abandoned it, and the question that all writers know came back to haunt me: How do I express reality? How do I write?

***

In a moment of despair, my first novel, That Smell, was born. It merely observed reality as it was, without attempting to interpret or explain it, at least on the surface. There was a certain suggestion in the selection of observed phenomena, and this choice was reflected in the language: the sentences are factual, short, devoid of similes and traditional rhetorical devices. free of the usual verbosity and digression found in Arabic narrative. The sentences are neutral and factual, referring to nothing, arranged in a breathless sequence that does not pause for analysis, scrutiny, or commentary. They observe everything, and all phenomena are given equal value. They simply observe, without regard for social traditions (it speaks very simply about sodomy and masturbation).

Nor does it concern itself with literary traditions (it does not shy away from clumsy construction or the repetition of certain verbs and conjunctions, nor is it concerned with the limited vocabulary used), but it allows for lyrical contrasts relating to the past.It was no coincidence that the novel was published with a quote from James Joyce, spoken by the protagonist of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “I am the product of this sex, this country, and this life… and I will express myself as I am.” It was as if this reference had resolved all my doubts about writing.

But I soon discovered that writing in the same way would lead to nothing but an accumulation of similar phenomena. The fundamental concern remains an understanding of reality, and an attempt to comprehend it, not merely observe it.

***

The possibility of this became clear to me in the subject of the High Dam. I saw in this massive engineering project a focal point that could bring together all the contradictions of reality. It was born in fierce confrontation with colonialism, both old and new, and involved the momentous undertaking of changing the course of the Nile, which had remained unchanged for thousands of years. It also required the introduction of new machinery and technologies and was carried out with popular enthusiasm under military rule, involving representatives of all classes. It even revealed the contours of the class that was coming to power: contractors, brokers, and agents of foreign companies.

In addition, the work on the project was divided into two phases: the first phase consisted of simple, obvious work, such as digging and filling on a massive scale, while the second phase involved more technical work, at a higher technical level and with more complex mechanisms.

Don’t revolutions and historical coups always go through these two stages? In the beginning, the goal is simple and clear. Everything is black or white. You’re either for or against. There’s enthusiasm and confidence in the future and in the ability to change the course of history. There is no time for reflection and analysis. Then the revolution is achieved and another phase begins, with a slower pace: the tasks are more complex, the goal is less clear, and shades of gray creep into the black and white. There is now “time to think” about what? About the mistakes of the first phase and the possibilities for the future.

***

Here, the subject matter is rich, allowing for the depiction of multiple aspects of reality, as well as another technical solution: achieving the greatest possible unity between form and content. The high dam itself consists of three parts: one facing south, another facing north, and a third, smaller one between them, which forms the focal point and is even called “the core.”

While the two outer parts are made of similar materials consisting of stones and sand of varying degrees of coarseness and fineness, the core is made of the most fragile material: earth. However, this fragile soil becomes the strongest point in the dam when arranged in a specific way that responds to the size of the project, its requirements, and the soil conditions, and then injected with certain materials, some of which are imported from abroad, specifically from the Soviet Union.

Here, a new reference phrase emerged, consisting of two lines of poetry by Michelangelo:

“No idea comes to the artist, however great he may be

It does not exist in the shell of the rock

All the hand that serves the mind can do

Is to unlock the magic of the marble.”

The rock is the master. Reality is the form.

***

The more I studied the engineering details of the dam’s construction, the characteristics of the materials used, the quality of the machinery, and the nature of the processes involved, all distributed in harmonious units, the more I was struck by the amazing possibilities that allowed me to continue with the narrative forms I love so much:

the short, factual, and neutral sentence; the lyrical sentence that evokes the past; the embedded document; and finally, the sentence that blends all of this into a warmer flow, in a precise focal point where total unity is achieved, a moment of salvation, a moment of action that explains and justifies, allowing us to understand reality and the possibility of changing it at the same time.

In a valuable study of this novel, Boutros al-Hallaq writes: “The novel’s novelty is that it does not refer to a reality that is independent of itself, outside of it, but rather attempts to approach it as closely as possible; it is reality itself… The linguistic meaning of the word does not refer to anything. Or to anything of importance. Its most extreme connotations are found in certain details here, such as the structure of the word. It dwells and settles in the compound word. Here, the structure alone conveys reality… or, more accurately, the structure here is reality. Do not seek anything from it, seek only from it itself. Perhaps here we arrive at the “word/action” that Adonis extols as having been born in Arabic poetry after the West adopted it in its purest form.

***

However, Al-Halaq soon goes on to discuss the predicament of the novel form in August Star, saying in the same study: The novelist actually depicts a post-machine world, while thinking he is depicting the present world. He expresses the crisis of post-industrialization… It is no coincidence that the artistic tool in the novel’s structure is borrowed from a society suffering from the crisis of industrialization, not from the predicament of modernity, i.e., the West. We are not revealing any secret when we say that the novel’s structure is borrowed from the modern European novel. There is a great similarity between this technique and the new forms adopted by the European novel more than ten years ago… The technique is borrowed in the novel’s form, as in industrialization, from the same source.”

This is an accusation that does not bother me at all, as long as I have objective justifications for the form in which the novel was born. The fact is that the impasse referred to is essentially the impasse of “The Barber” itself.

Listen to him say in the same study: “Modernity in our case is in fact a fragmented world in which the old customs that organized the old society and reflected its perceptions of itself, its ideals, and the myths that nourished its own dynamics have been destroyed, and new customs, even new laws from a different world, have been imposed to replace the old customs, causing society to explode, fragment, and disintegrate. This is modernity in our country: not a new situation with its own momentum that brings together the various elements of society in a new, harmonious structure, but rather a current impasse in the form of a crisis of governance and industrialization that must be overcome with great difficulty.”

***

The Barber’s Dilemma is that he wants modernity without crisis, without contradictions, through a smooth, harmonious process, modernity without shock, without industrialization or machinery, so that we do not import anything that would destroy the unique dynamism of our great backward society.

He wants a narrative that does not cause shock, that is unlike any similar European or Western narrative, even though we imported this very form of expression from the West with the first machine that reached us, when society had reached a level of development that required both.

But is the dilemma really Al-Hallaq’s alone?

August Star was born out of a cold prison of strict rules that I thought represented my own path. These are not just rules of writing technique, but also a view of life based on observation and suspicious involvement.

Within the cold walls of this prison, I longed for the freedom under which every great work was written, imbued with a magic that made it penetrate the heart.

***

But getting out of prison is always harder than getting in. It took several years, during which I migrated to another side of reality: nature. I set about writing a collection of stories and novels about the world of animals and plants, giving free rein to my desire for free writing based on plot, adventure, excitement, and humor, unbound by strict rules and completely uncommitted to scientific facts, but completely committed, once again, to reality.

Meanwhile, society was undergoing widespread changes. The great modernist project of the 1950s and 1960s ended in complete failure, and its proponents threw up their hands, resigning themselves to a position of dependency. Within a few years, everything returned to the way it was: confiscated money and land were returned to their owners, the value system was adjusted, workers lost their privileged position and returned to the bottom, nascent industries were aborted or stagnated, imperialism regained its old positions, either openly or hidden behind multinational companies, Israel ran rampant without restraint, and reactionary Salafi ideology spread on two wings: oil money and frustration.

***

This situation seemed less ambiguous than before. Would I say that the picture lost its grayness and was reconstituted in two contrasting colors, black and white? But there is a huge difference between these two colors now and between them in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when the new realism was born in literature and art. The images may be as clear now as they were then, but they are certainly more profound and complex than before. It is natural, then, that their expression should oscillate between a focus on Westernization and obscurity, and a return to tradition. But what initially manifested itself as a protest against reality, sometimes by alienating it and sometimes by depicting it in a servile language, gradually turned into acceptance and approval, through a shift away from enigmas, or a transition from the language of the Mamluk decline to the language of Sufism… that is, from one step forward to ten steps backward.

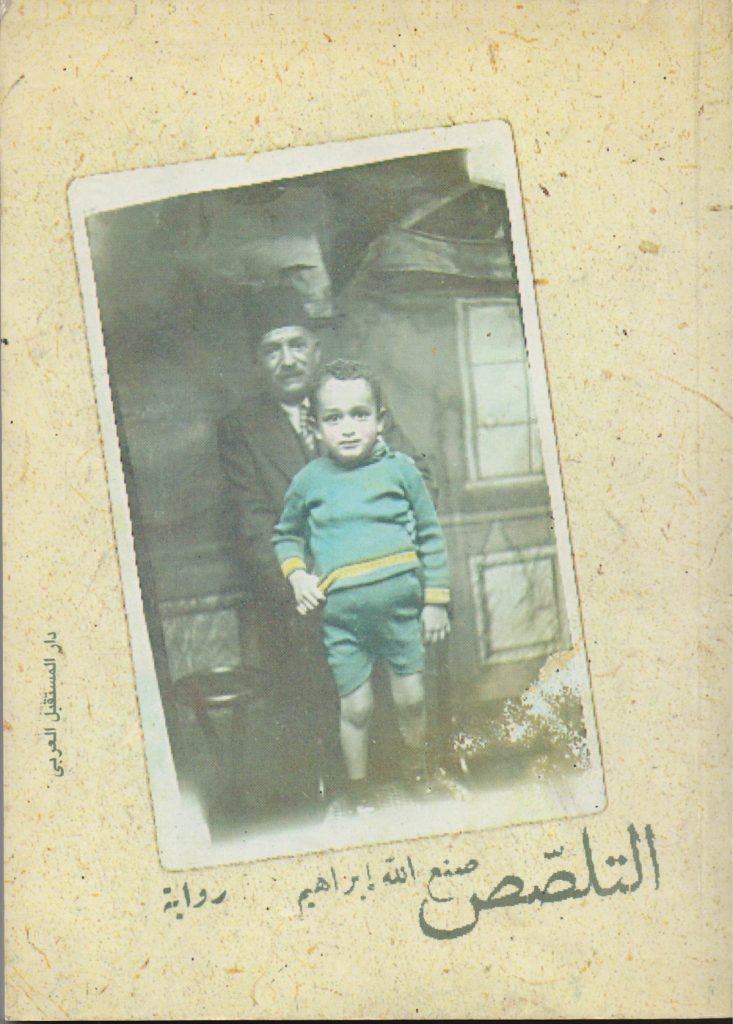

Once again, the familiar question arose: how do I express reality, how do I write? In a moment of despair, I returned to a small piece of paper on which I had jotted down years ago a preliminary description of a defenseless individual facing a committee of examiners and responding to vague questions, the ultimate goal of which was to humiliate and degrade him.When I wrote this piece, it seemed to me that developing it into a complete work would require removing all realistic connotations, which would lead directly to the world of Kafka. At the time, I was not ready to stray from what I believed to be my own path, so I set it aside. I returned to this paper after long training in breaking the rules and prolonged observation of the cycle of collapse and dependency. Without worrying about Kafkaesque overtones, I began writing the novel The Committee with a great deal of spontaneity.

***

I soon strayed from the Kafkaesque path, as well as from my previous path; documents crept into the pages, cold neutrality gave way to black humor, sentences became long and open to similes, digressions, linguistic tricks, and everything I had previously avoided.

Direct irony replaced the reportage tone and apparent neutrality, and malicious assassination replaced passive objection. Most important of all, the traditional plot slipped shyly into the text.

When I found a new focal point similar to that of “August Star” that could bring together the fragments of Arab reality in the 1980s, namely “Beirut,” the story with its plot fell into its natural place, built on the foundations of the art of storytelling since time immemorial: traditional chronology and psychological characterization. But the narrative surrendered itself to the actual sentence, short, factual, seemingly neutral, which imposed itself in the face of a highly ambiguous subject with multiple angles and points of view. This is the same reason that gave way to the document and pushed it to take center stage in the novel’s structure.

***

In a study of “August Star” published in the magazine Alif (1982), Siza Qasim wrote: The issues facing (Arab) literature today are fundamentally epistemological.

Literature is the privileged, and perhaps the fundamental, medium of knowledge: knowledge of the world and knowledge of the self. In societies where truth is concealed, distorted, and suppressed, the function of literature is to reveal and expose the truth. Today, Arab writers have become the bold spokespeople for society. This has resulted in literature that is steeped in the problems of everyday life and directly linked to the media and communication, to the extent that it has replaced the channels through which everyday knowledge is transmitted and, in some cases, has become the only truly authentic, if not immediate, expression of pressing social issues.

I do not subscribe to this view unreservedly. History has taught us to be cautious about making categorical statements about the function of literature or the social role of creativity. We have also learned that there are many paths that lead to reality, some of which may at first glance seem far removed from it.

When attempting to summarize a creative experience, it suffices to say that it is yet another endeavor, among many diverse endeavors, to grasp, through available tools and based on a unique mood and constitution, that elusive goal throughout the ages: reality.

Sanallah Ibrahim’s testimony was published in the Beirut magazine Mawaqif in November 1992.