British Museum Loans Egyptian Artifacts to India, Sparking Debate Over the Rosetta Stone

The British Museum has sent 80 Egyptian and Greek artefacts to India for a three-year loan—but when photos showed the Rosetta Stone among them, Egypt and Greece were left asking a pointed question: Why are our most iconic treasures being used to repair Britain’s relationship with a different former colony? Amani Ibrahim reports.

The controversial move, part of a 15-year partnership with Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya museum, has sparked debate over whether the iconic stone was actually transferred or if a replica is on display. More fundamentally, it has raised questions about whether long-term loans to third countries represent a new strategy to sidestep restitution demands, and whether Egypt can ever reclaim its heritage from one of the world’s most powerful museums.

Colonial Reparations Through Loans?

The British Museum has transferred 80 Greek and Egyptian artefacts to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) museum in Mumbai, India. According to Art News, the artefacts will be on display in a study hall at the Indian Museum for three years.

This move is part of the British Museum’s plan to share artefacts from its collection with former British colonies in an attempt to address the legacy of Britain’s colonial history. It falls under a 15-year partnership between the British and Indian museums.

The “Networks of the Past” Exhibition

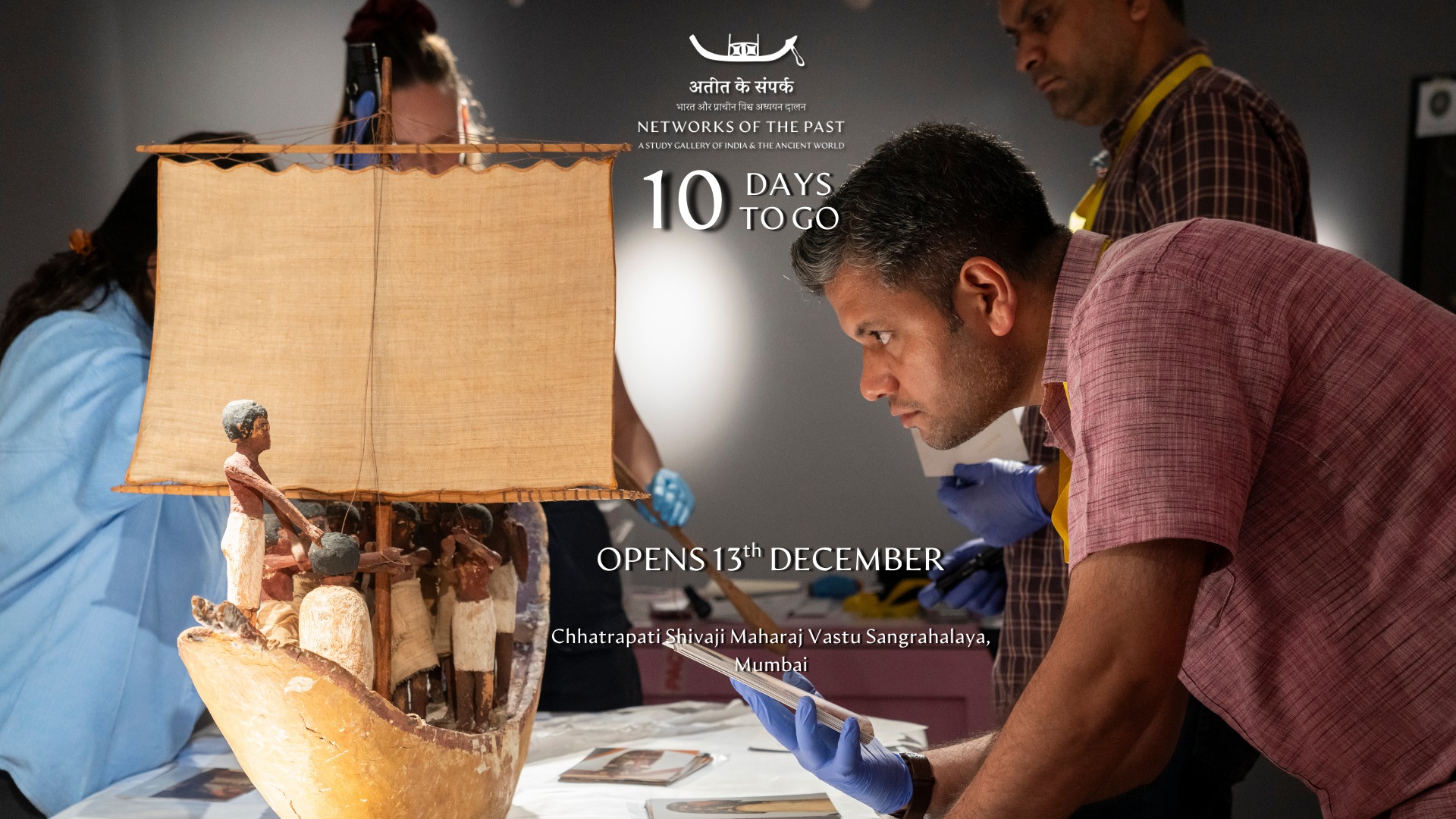

The Egyptian artefacts are being displayed as part of an exhibition titled “Networks of the Past,” which opened in India recently. The exhibition features a vast collection that documents ancient Indian history and its global connections during the antiquity period.

The Transferred Egyptian Artefacts

The Indian news outlet ETV Bharat covered the exhibition, which includes 300 artifacts on loan from 15 countries worldwide. It aims to highlight multiple civilisations,including India, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, Persia, and China,and to show how nations were interconnected 5,000 years ago through trade, writing, religion, and art. Preparations took five years.

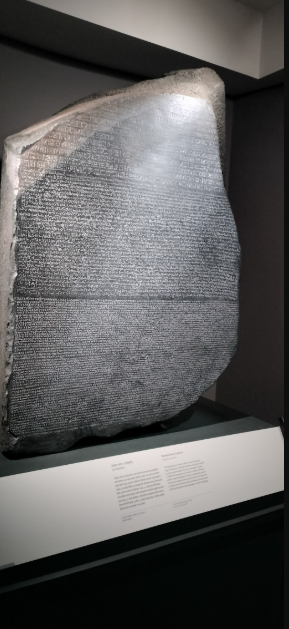

Was the Rosetta Stone Actually Moved to India?

The number and description of the Egyptian pieces transferred have not been officially announced. However, according to ETV Bharat’s coverage, the Egyptian Rosetta Stone,which has been at the British Museum since 1802, was displayed in India with an identification label in both English and Hindi.

No other source has confirmed or denied whether the actual Rosetta Stone was loaned to the Indian exhibition, or whether the displayed item is a replica intended to support the exhibition’s theme.

Other displayed items include an intricate wooden model of an Egyptian river boat dating back about 4,000 years, a wooden statue of oxen pulling a plough, and Ptolemaic-era limestone canopic jars used in mummification.

Rethinking Colonial History

Dr. Hussein Abdel Basir, former General Director of the Giza Pyramids and Director of the Antiquities Museum at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, sees the loan as part of a new international context in which major museums are seeking to re-examine their colonial history and attempt to build cultural bridges with countries and peoples that were part of that history.

He told Bab Misr that temporary exhibition exchanges can be a positive tool for introducing the world’s peoples to ancient civilisations, including Egypt’s, provided they’re conducted within a transparent scientific framework, with strict guarantees for preservation and clear respect for the rights of source countries.

The Rosetta Stone Transfer Debate

The Egyptian archaeologist confirms that the debate surrounding the Rosetta Stone needs decisive clarification. As of now, there is no reliable official announcement confirming the transfer or loan of the original Rosetta Stone to India.

“What has appeared in some media coverage might be a photograph, a replica, or a visual treatment serving the exhibition’s concept,not the original artefact itself, which is common in international exhibitions,” he said. “Any movement of the original artefact, if it occurred, must be announced officially and with full transparency due to its exceptional global value.”

Cultural Exchange or Political Message?

Meanwhile, Dr. Monica Hanna, a professor of archaeology and cultural heritage, asserts that this move carries dual significance. On one hand, it’s presented as a “cultural exchange” reflecting the universality of heritage. Politically, however, it’s a clear message that the British Museum still considers itself the sovereign decision-maker regarding the movement of artefacts, even disputed ones.

She believes choosing India, a post-colonial nation, gives the move a symbolic dimension that suggests transcending the colonial past while subtly reproducing it.

A Temporary Tactic or Strategic Shift?

Regarding whether this loan represents a shift in the museum’s policy toward countries demanding the repatriation of their heritage, or merely a temporary measure to placate them, Dr Hanna clarifies it’s a temporary tactical step, not a strategic shift.

“The museum hasn’t changed its legal or ethical stance on restitution issues,” she adds. “Instead, it uses loans as a politically less costly alternative to returning artefacts and as a means of showing flexibility without conceding ownership.”

A Message of Soft Power

On why Egyptian and Greek artefacts were chosen for loan to India, Dr Hanna notes that Egyptian and Greek civilisations represent the symbolic foundation of the “world civilisation” narrative upon which the British Museum builds its identity. They’re also the most famous and audience-attracting, while simultaneously being the most politically sensitive in terms of restitution demands. Displaying them is a message of soft power.

Regarding the circulation of an image of the Rosetta Stone in press coverage of the exhibition, whether original or replica, Dr Hanna suggests it’s likely a replica. She explains that the original Rosetta Stone is one of the most sensitive artefacts, and its transfer involves significant technical, political, and legal risks. The British Museum is also very keen not to set a precedent by moving the original stone outside London.

The Power of Using Symbols

Dr Hanna explains that loaning replicas has become a recognised tool in modern museums, especially for educational purposes. “But the problem,” she notes, “lies not in using the replica, but in not declaring it clearly to the public.”

She adds that using a symbol is often politically and culturally more powerful than displaying the original artefact because it evokes the meaning, controversy, and history without risking the object. The image of the Rosetta Stone, even as a replica, summons all the debates about colonialism, knowledge, and power.

Undermining Restitution Claims?

Dr Monica Hanna explains that, legally, the British Museum has the right to loan disputed artefacts to third countries, as it considers itself their owner under current British law, specifically the British Museum Act of 1963. However, from the perspective of international law and modern ethical norms, loaning disputed items without the consent of the source country is problematic. It could be interpreted as directly undermining restitution claims.

A False Compromise?

Could long-term loans be considered an unannounced alternative to addressing restitution demands, especially concerning Egyptian artefacts? Dr Hanna affirms that this trend is becoming clear. Long-term loans are being used as a “false compromise”: neither genuine return nor outright refusal.

She clarifies that this policy keeps artefacts away from their homelands and drains the political momentum of restitution claims over time. She adds that if legal ownership belongs to Egypt, even if the artifact is on loan or deposit, it shouldn’t be loaned to a third party without official and explicit consent from the Egyptian state. Any action otherwise constitutes a breach of cultural sovereignty.

The Right to Restitution

For his part, Dr Hussein Abdel Basir confirms that loaning artefacts doesn’t mean correcting the historical injustice of colonialism; it remains a limited symbolic step. “The real issue, especially concerning Egyptian artefacts, is the right to restitution, not merely temporary loans,” he states.

He emphasises that the Rosetta Stone and other unique pieces represent an integral part of Egyptian memory and identity, and their rightful place is in Egypt.

Abdel Basir concludes by stressing that international exhibitions like “Networks of the Past” could represent an important opportunity to highlight the civilizational interconnectedness between Egypt, India, and the ancient world,provided they don’t become a way of glossing over colonial history and loans aren’t used as a substitute for a serious and fair discussion about returning artefacts to their homelands. “This is a discussion that can no longer be ignored in the 21st century,” he said.

A Strategy of Delay?

Dr Monica Hanna points out that Egypt has the right to demand its artefacts in all cases, regardless of risks associated with transport or display techniques.

She indicates that such exhibitions may contribute to cultural engagement, but they also postpone resolving contentious issues related to artefact ownership, “delaying resolution more than approaching a solution.” While they may create cultural awareness among the public, they allow holding institutions to continue avoiding the core problem: “Who holds the moral and historical right to this heritage?”

Why Not Loan Indian Artefacts Back to India?

Regarding why Egyptian and Greek artefacts were sent to the Indian museum rather than Indian artefacts being returned, Dr Nicholas Cullinan, Director of the British Museum, told The Telegraph that the project represents a new model for working with nations seeking reparations for colonialism. He said, “Former empire nations welcome striking long-term deals about artefacts that are in Britain.”

Ongoing Disputes

Cullinan explained that transferring these artefacts results from prolonged disputes over returning treasures held in Britain, including Indian artworks, Ghanaian gold, Ethiopian sacred tablets, the Benin Bronzes, and the Elgin Marbles (also known as the Parthenon Sculptures, claimed by Greece).

He confirmed that the British Museum seeks cooperation, but simultaneously won’t put Britain in an awkward position or deal with demands based on a “profit and loss” logic when handing over cultural treasures.

“Taking positive steps toward some countries doesn’t require embarrassing others,” he added. “This approach is very beneficial because the real role of museums should stem from cultural diplomacy as a tool for rapprochement and understanding.”

The ‘Woke’ Movement

The Telegraph notes that some observers believe the British Museum has deliberately distanced itself from the impulses of the so-called “woke” movement, even as many cultural institutions rapidly adopted decolonisation discourse and reframed their collections for the public.

However, restitution demands have been repeatedly rejected, citing the British Museum Act of 1963, which prohibits the institution from disposing of its holdings.

Loan Agreements as a New Approach

So why did Britain agree to send Egyptian and Greek artefacts to India despite restrictions imposed by British law? According to The Telegraph, this is due to the British Museum’s new administration under Dr Cullinan, who took over in 2024 and is working to reduce the intensity of disputes by proposing alternatives based on loan agreements lasting up to three years.

“There is another model of cooperation I see as more positive, away from the logic of profit and loss, or the all-or-nothing choice some propose,” Cullinan said.

Demands from Egypt and Other Nations

The British Museum has received calls from several governments worldwide to return artefacts from its collection, including from Greece and Jamaica.

According to a previous Telegraph report published in 2024, similar appeals were issued by officials from museums and researchers in Egypt, China, and Sudan. India has also demanded the return of cultural treasures looted during the colonial period, including the Koh-i-Noor diamond (now part of the British Crown Jewels) and the Amaravati Marbles (Buddhist sculptures from southern India).

The newspaper revealed that the British Museum is holding private talks with four foreign governments regarding the return of some pieces from its collection. A document seen by The Telegraph shows the museum has received 12 separate formal requests since 2015 for artefact returns, four of which were submitted by foreign governments through confidential diplomatic channels.

“Each case has its particularities, and you cannot deal with two cultures or two countries or two regions with the same criteria,” Cullinan said. “Some files are more complex than others, yet the museum continues its attempts.”

Can Egypt Recover the Rosetta Stone?

The British Museum confirmed that the Rosetta Stone, transferred from Egypt to Britain in 1802 after French forces surrendered it following Napoleon’s defeat, was not among the four artefacts officially requested for return so far.

Speculation arose about the possibility of its return after the museum dropped the “Rosetta Project” from its £1 billion renovation plan in the summer of 2024.

The Black Lives Matter Effect

The Telegraph notes that British museums have, since 2020, pursued efforts to rectify policies of retaining colonial-era artefacts, following the protests of the Black Lives Matter movement that swept the UK and sparked broader reckonings with colonial history.

These protests pushed many museums to launch initiatives to return artefacts looted during colonial periods to their countries of origin.

Among these steps, the Horniman Museum in southeast London, along with Oxford and Cambridge museums, returned artefacts to their countries, including the Benin Bronzes demanded by Nigeria, which were looted by British forces during a punitive expedition in 1897.

A New Chapter or More of the Same?

The British Museum’s loan to India may represent what Dr Cullinan calls a “new model” of cooperation,but for Egypt and Greece, it raises an uncomfortable question: Is this genuine progress toward cultural restitution, or simply a more sophisticated way of maintaining the status quo?