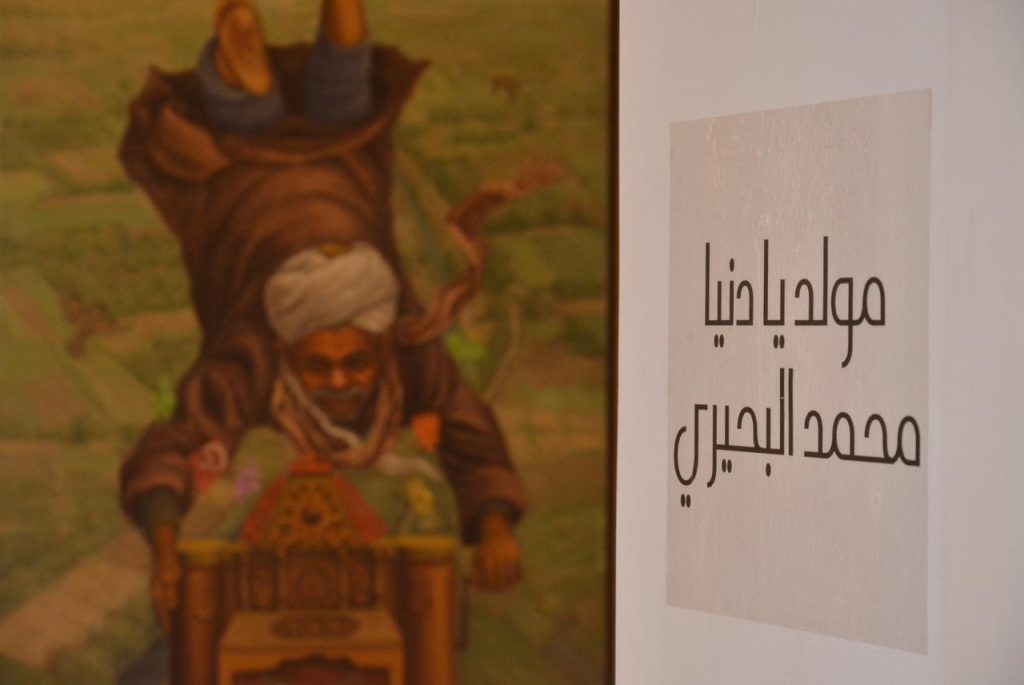

Dreaming in Color: An Egyptian Artist’s Surreal Journey Through Moulids and Modernist Legacy

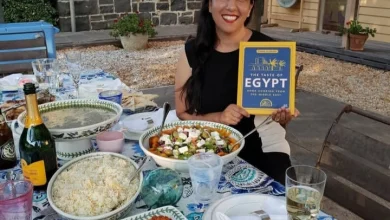

In his exhibition ‘A Festival, O World,’ visual artist and scholar Mohamed El-Behiry navigates the mystical spectacle of Egypt’s street carnivals, weaving doctoral research on surrealism into a vibrant tapestry of personal and collective heritage. Through 31 paintings and sculptural works, he bridges Cairo’s avant-garde past with its living folklore, offering no easy answers—only portals to wonder.

Moulid as Inspiration

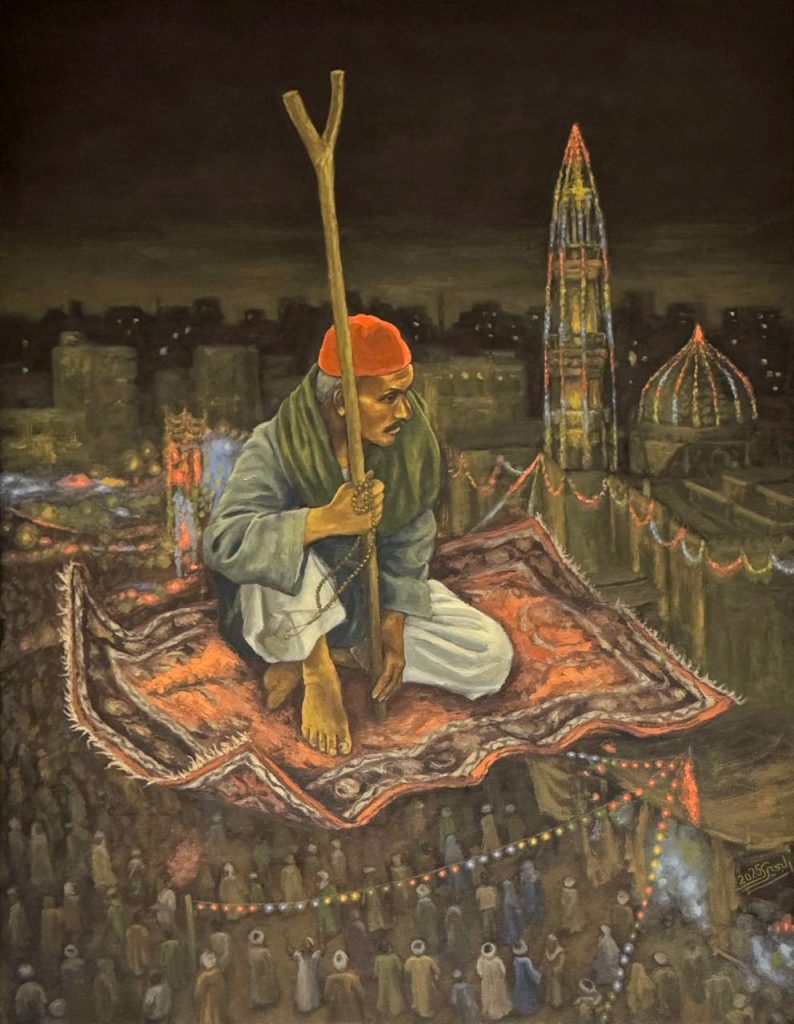

At the heart of Egyptian cultural tradition lies the Moulid, a vibrant street festival that honours a Sufi saint. This celebration is a profound communal tapestry, a spiritual gathering, a pilgrimage, a public feast woven with music, performance, and shared joy. It is from this deeply rooted heritage that visual artist and academic Dr Mohamed El-Behiry draws his inspiration. In his solo exhibition “A Festival, O World” (Moulid Ya Donya), he re-envisions its iconic symbols. The reed flute, the Sufi devotee, the wooden hobby horse, the festive ornaments through a surrealist lens, fusing personal recollection with collective memory. The exhibition is on view until December 14 at Art Talks Gallery in Cairo’s Zamalek district.

The Works on Display

El-Behiry, an assistant lecturer at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Alexandria University, presents 31 oil paintings alongside drawings on wooden sculptural forms. While his techniques vary, a unifying thread is the spirit of the Moulid, which ties the collection together like a visual melody, even as the style shifts from piece to piece.

Speaking to Bab Masr, the artist shared the backstory of a project that unfolded alongside his doctoral studies: “The period of work and study took about two and a half years.”

Between Irony and the Mystical

The exhibition’s scope spans playful joy and spiritual solemnity, a duality at the heart of the Moulid itself. Viewers encounter a flying horse ferrying festival-goers, a vendor of paper hats ascending with his horn, and men in traditional galabiyas suspended mid-air, clutching a watermelon. El-Behiry unpacks this juxtaposition: “Surrealism, by its nature, is ironic toward reality. It challenges the conventional and its set arrangements, drawing on the power of imagination to produce an alternative reality.”

A signature piece is the painting “Melodies of the Pianola,” which the artist describes as capturing the exhibition’s core spirit. It lifts the entire festival into a soaring, airborne visual field. “It was a work not planned in advance,” he notes, “but one that gradually took shape through the stages of execution.”

Entering the World of the Moulid

El-Behiry’s focused engagement with the Moulid is a recent development, following earlier periods of exploring Egyptian environments, celebrations, and heritage through free expression. “When I started working on the exhibition, I drew closer to the world of the Moulid,” he says. “So the connection between the works—even if indirect—is that the essence of the Moulid is present.”

A shared atmosphere of joy, ritual, and folk symbolism permeates the show. This is El-Behiry’s second solo exhibition, following “A Pie in the Sky” in January 2023, which centered on themes of hope and delight. He reflects, “After that show, I noticed the idea of the Moulid was pulling me in strongly.”

An Academic Journey in Parallel

The creative process for the exhibition coincided with El-Behiry’s preparation of his doctoral dissertation, which dedicated a chapter to documenting this practical, artistic experiment. The theoretical arm of his research simultaneously broadened his artistic perspective.

His dissertation is titled: “Surrealism in Egypt between the Thought of the ‘Art and Freedom’ and ‘Contemporary Art’ Groups (A Comparative Analytical Study).” It maps surrealism’s trajectory within Egyptian art history from the 1930s and 1940s into the 1950s. A period when Egyptian artists were not just copying European modernism but actively reshaping it into a tool for local expression and critique.

“I chose this topic for its contribution to forming a comprehensive archive that provides a non-fragmented understanding of Egyptian surrealism,” he explains. “There are missing links that need re-reading. It also allows us to track points of convergence and difference between the two groups, which is crucial for understanding the path of modernist painting in Egypt and the intellectual and artistic tensions that shaped the modern scene.”

Surrealism’s Route from Paris to Cairo

The dissertation includes a foundational chapter outlining its general framework, followed by an analysis of surrealism’s birth in Paris and its transmission to several countries, including Egypt.

The research argues that surrealism’s arrival in Egypt resulted from direct contact with the movement’s European epicentre, at a moment when the local cultural landscape was ripe for such a revolutionary current. “Surrealism, when it arrived, sparked widespread activity,” says El-Behiry. “It pushed Egyptian arts and culture into a more daring and liberated phase.”

Memory as Muse

The academic work delves into the practices of pioneers like Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar and Hamed Nada, who lived in neighbourhoods adjacent to famous Moulid sites such as Sayeda Zeinab and El-Khalifa. Their work expressed these festivals from an insider’s perspective, much like Bruegel depicted village life or Goya captured local festivals but filtered through a distinctly Egyptian surrealist sensibility.

El-Behiry seeks to recapture a similar intimacy. The Moulid has been part of his memory since childhood in Kafr El-Zayat. Family trips with his late grandmother to the Moulid of El-Sayed El-Badawi in Tanta and the Moulid of Ibrahim El-Desouki in Desouq were annual traditions.

“Those scenes stayed fixed in my mind until I decided to draw inspiration from them for my work,” he says, “alongside field visits and ongoing documentation of popular celebrations.”

Reanimating Egyptian Folk Symbols

For El-Behiry, revitalizing heritage is a fundamental artistic duty; it is “an inexhaustible sea” one can return to repeatedly to uncover new strata, provided one looks with fresh eyes.

His creative process relies on both memory and direct lived experience. He asserts that real-world engagement grants a truer expressive capacity, supplemented by archival research when precise details are required.

Where Folklore Meets Surrealism

El-Behiry elaborates on merging folk tradition with surrealist practice, noting its origins lie in the early days of the surrealist movement itself. European pioneers and later those in Egypt and beyond looked to folk arts, finding in them a wellspring of symbols that channelled society’s “collective unconscious” and enabled the creation of new mythical rituals and modern legends.

He applies this methodology to Egyptian heritage, treating popular tradition as a living, malleable substance. By fusing it with surrealism, he aims to construct a new visual realm imbued with the spirit of tradition. “The fusion happens in a space where heritage encounters imagination,” he states. “From that, a personal artistic world is born, one that re-presents Egyptian heritage in a contemporary form.” This blend, he insists, compromises neither folklore’s authenticity nor surrealism’s modernity.

Deconstructing and Rebuilding Memory

El-Behiry views the re-contextualization of folk symbols as an attempt to preserve cultural memory through deconstruction and reassembly. “Preserving memory lies in re-engaging with it, deconstructing it through analysis, and presenting it in a new mould,” he argues. “This renews memory, confirms its authenticity, and ensures its continued presence.”

He observes that younger generations in Egypt today are less connected to these folk reference points, leading to a different reception of symbolic language compared to prior generations.

A Welcome Multiplicity of Meanings

“When people who have lived these rituals and know the details of folk heritage visit the exhibition, the connection with the works happens faster,” El-Behiry remarks. “But my paintings don’t offer ready-made answers. Instead, they open a door to interpretation and multiple explanations.” He sees this openness as intrinsic to the nature of art itself.

This plurality of readings, he suggests, grants an artwork a longer life. The world of the Moulid, with its colours, motion, rituals, and layers of collective imagination, cannot be confined to a single artistic approach, whether realistic, expressionist, or surrealist.

.

The Influence of Max Ernst

El-Behiry’s interest in surrealism began during his university studies, though deeper immersion came after graduation. Over time, his focus narrowed on this movement, captivated by its enduring power and the relative scarcity of Arabic-language resources analysing it.

For his master’s thesis, he focused on the methods of Max Ernst, a foundational surrealist. “I couldn’t find an Arabic study that analyzed his works and his innovative techniques, which turn a painting into a riddle that needs decoding,” he explains. “I wanted to uncover the secrets of that world and learn from them.”

The Distinct Path of Egyptian Surrealism

El-Behiry points out that surrealism’s introduction to Egypt in the 1930s followed a distinct path from its European origins, entering a uniquely local context. Egypt was then taking its first steps toward modern art amid turbulent social and economic conditions that inevitably shaped artistic expression, similar to how Mexican muralism or the Harlem Renaissance blended modern techniques with specific cultural and political realities.

He adds that imagination as a creative force is not foreign to Egyptian visual culture. Its roots extend deep into ancient Egyptian art, with its mythical visions and fantastical imagery that can be seen as early incarnations of a local surrealist sensibility, much as Hieronymus Bosch’s work is sometimes viewed as a proto-surrealist precursor in the West.

The visual transformations occurring across the Arab world, he suggests, also fostered an artistic sensibility different from the European experience, which built upon a long legacy from the Renaissance to Modernism. This difference endowed Egyptian surrealism with its own particular stylistic and intellectual character.

Surrealism as Cultural Resistance

In its historical moment, El-Behiry contends, Egyptian surrealism constituted a form of cultural resistance. The “Art and Freedom” group, led by figures like Georges Henein, Ramsis Younan, and Fouad Kamel, mounted an intellectual and artistic revolt against the preceding generation of artists.

They rebelled against the mainstream, seeking to create an aesthetic and intellectual shockwave to disrupt the romantic templates they saw as inadequate for expressing society’s upheavals and profound tensions. Thus, Egyptian surrealism emerged as an act of refusal and a desire to dismantle reality, reconstructing it through the logic of freedom, imagination, and desire, paralleling how surrealism in other contexts often served as a vehicle for political and social critique.

Continuity and the Local Context

The energy of surrealism did not end with “Art and Freedom.” By the late 1940s, the “Contemporary Art” group inherited a share of this provocative spirit but expressed it differently.

Artists like Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar, Hamed Nada, and Samir Rafie re-rooted surrealism within a popular, local context. They exchanged the shock of political rebellion for the shock of the symbolic image, drawn from popular culture and collective imagination. In this way, surrealism’s influence expanded from the plane of intellectual revolution with “Art and Freedom” to the plane of constructing a new visual vocabulary with “Contemporary Art”. A vision embracing the mythical, the folkloric, and the magical, continuing its act of resistance through art, but now from the heart of popular reality, rather than from outside it. This journey from avant-garde theory to grounded, symbolic practice mirrors broader global patterns in 20th-century art, where modernist movements were adapted, localised, and reinvented far from their points of origin.