The Lost Temple of Beris: How Egypt’s Desert Swallowed a Roman-Era Pilgrimage Site

The desert reveals its secrets only to those who listen to its silence and stillness. In the presence of the endless sands, time itself seems to dissolve; years become mere grains swept by the wind, revealing yet another archaeological enigma on the outskirts of Kharga, the capital of Egypt’s vast New Valley Governorate.

This site, passed daily by locals who see only an unremarkable hill, or tiba, is in fact a layered archive of untold stories and ancient beliefs. They walk, unaware, over accumulations of history over the lost temple of Beris.

A Hill, or a Gateway? The Story of Beris

For generations in the New Valley, elders whispered about forgotten “treasures” north of Kharga. This led archaeologists to reinvestigate the legend of The Sanctuary of Beris. The journey there is not just a trip into the desert but a passage through time.

Near the well-known area of El-Lakhkha lies a site known locally as “The Shadow”, a dark, desolate, yet strangely compelling place. Modern residents know it simply as a pile of rubble. In truth, it is a stone chronicle of human faith, fragility, and the eternal search for salvation. Under the harsh vertical sun, sharp shadows cut across its ruined walls. To understand them, we rely on archaeologists who have dedicated careers to deciphering this mystery.

A Rock-Cut Complex, Not a Temple

Mohamed Ibrahim, General Director of Antiquities for the New Valley, clarifies the site’s significance. Located 250 meters northwest of El-Lakhkha’s main ruins and dating from 140 to 335 AD—a period spanning late Roman rule in Egypt. The complex architecture is more than an engineering study. It is a physical record of the evolution of human thought and ritual across centuries.

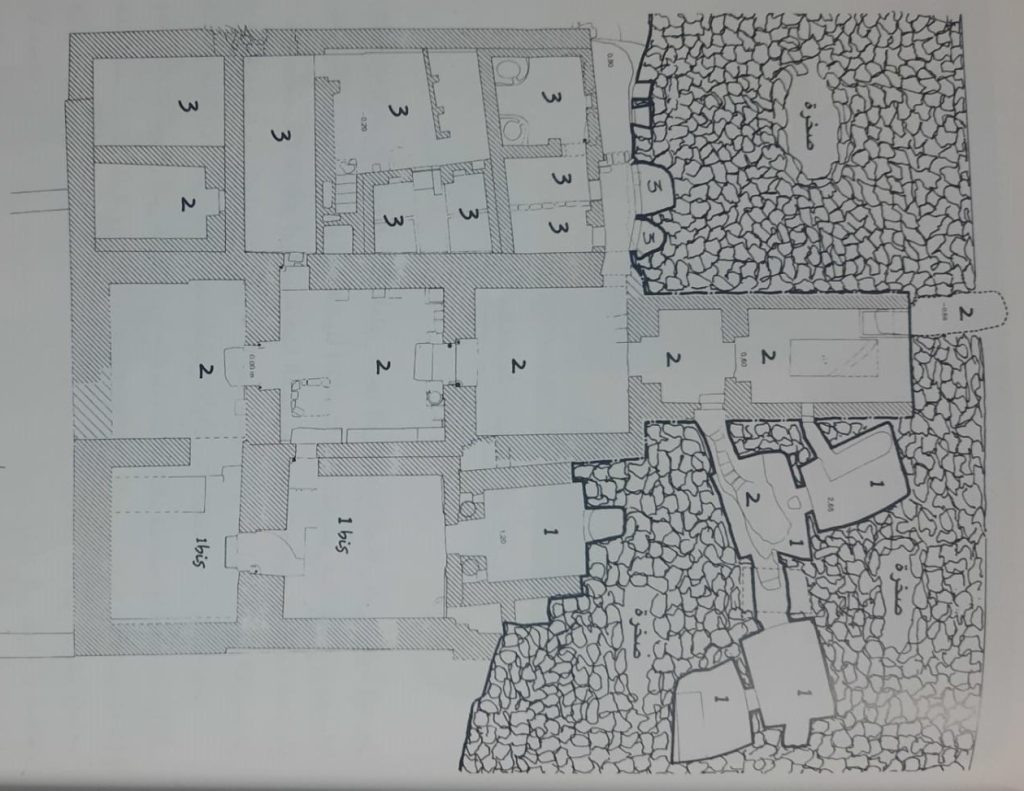

What we see is not a single, designed temple. It is a unique semi-rock-cut complex, a rare fusion of construction techniques added in successive phases, each responding to new needs.

Evolution of a Sacred Space: From Tomb to Pilgrimage Site

Ibrahim traces the site’s physical and spiritual growth. It began simply: a burial corridor and a few funerary rooms. A small hermitage for solitary prayer was added outside. Later, builders carved deeper into the bedrock, creating new chambers and descending passages—as if drawing closer to the earth’s secret core.

This expansion mirrored its changing role. Ibrahim Mohamed, former head of the Tourism Promotion Authority, highlights the human story. The discovery of fine textiles within suggests this was no ordinary burial. It was the tomb of a revered, pious figure—a local holy man.

Veneration for this “righteous man” grew. His tomb became a sanctuary for the distressed, then a destination for pilgrim caravans crossing vast deserts. Its popularity peaked between 140 and 325 AD, a time of profound religious change as traditional Egyptian and Roman beliefs began to interact with early Christianity

The Language of Color and Light

Mansour Othman, a former senior Islamic antiquities inspector, notes the site’s artistic sophistication. The outer chamber, made of mudbrick, is a hidden gem adorned with vibrant paintings. Circular motifs bordered in green on red backgrounds are symbolic: green for life and resurrection, red for strength and blood.

The entrance to the inner rock-cut chamber is framed in stark white plaster. This deliberate contrast created a “harmony” of dimensions and a powerful visual metaphor: a bright portal of hope for pilgrims emerging from dark, confined passages. The builders of Beris were masters in the use of space and color to shape spiritual experience.

The Fall into Silence: How a Shrine Was Lost

Bahget Ahmed Ibrahim, another former Antiquities Director for the region, narrates the site’s dramatic end. He connects its decline to the tectonic religious shifts of the late Roman Empire. As Christianity gained official favour in the 4th century, its clergy discouraged traditional practices such as the veneration of saints and pilgrimage to non-Christian tombs.

For Beris, this was a death sentence. The pilgrim caravans ceased. The site was abandoned. Then, as Bahget explains with regret, the desert reclaimed its own. Relentless winds buried the exposed structures, sealing the inner passages and the once-active burial chambers, returning Beris to obscurity under the dunes.

The City of the Dead: The Adjacent Necropolis

The main complex is flanked by a vast necropolis (al-Gabana). This “city of the dead” features unique stone tombs, carved directly into rock or built from limestone. Their access is particularly eerie: deep vertical shafts lead down to burial chambers, a design meant to protect and inspire awe for the deceased.

Excavations here have yielded treasures resistant to time: wooden coffins, pottery used in burial rites, and other artefacts.

The Priceless Discovery: A Face from the Past

The most stunning find was a funerary mask of extraordinary craftsmanship. Described by experts as “breathtakingly vivid and precise,” this mask now displayed in the Kharga Museum, is the only surviving object with clear human features. It stares out with wide eyes, seeming to hold the stories of a lost community and its saint, who suffered a second death when memory of him faded.

Artifacts in the Museum: Tangible History

Tarek El-Qallawi, Director of the Kharga Museum, confirms that key artefacts from Beris are housed there, including a statue of the falcon-god Horus, pottery, lamps, and incense burners. These objects sketch a picture of daily ritual life.

He identifies the tomb’s occupant as Saleh Beris, a deified local noble from the 2nd century AD. The shrine evolved from a simple chapel into a multi-room complex. 1991 excavations revealed its former splendour: domes, walls decorated with plaster painted to mimic marble. Testaments to a site that was once a beacon in the desert, now whispering its secrets only to those who choose to listen.