Joyce Mansour… The Tuberose Baby Girl

(1)

I love surrealist paintings, and I adore all kinds of art, especially those that break away from the ordinary and soar into a wider space. I have seen many of their paintings in Egypt, and around the world I have seen paintings by many of them who have passed into history. I have read wonderful books by writers such as Samir Gharib about the movement in the world and in Egypt.

Recently, this world has opened up to me through the artist, poet, musician, and translator Mohsen Al-Balasi, and his wife, the poet, short story writer, and Ghada Kamal Ahmed. I follow their activities on Facebook and read what they write about literature and art, amazed by the language and emotions. I finally read stories by Ghada Kamal Ahmed entitled “The Man Who Ate the Clock,” and I referred to them in a post expressing my admiration and amazement at the distinctive artistic images.

***

Visual art, like cinema, has been a major influence on my literary work. Surrealism has seeped into my novels and stories in some scenes, and I realize this after I write. For example, I have very short stories titled “What Remains of Dreams” that reflect this, and it has also seeped heavily into my novel “The Cyclops” and others. I laugh a lot at what is around me, which is beyond imagination in its absurdity, and I call it, as the average person would, a surreal scene, even though they do not know what surrealism is.

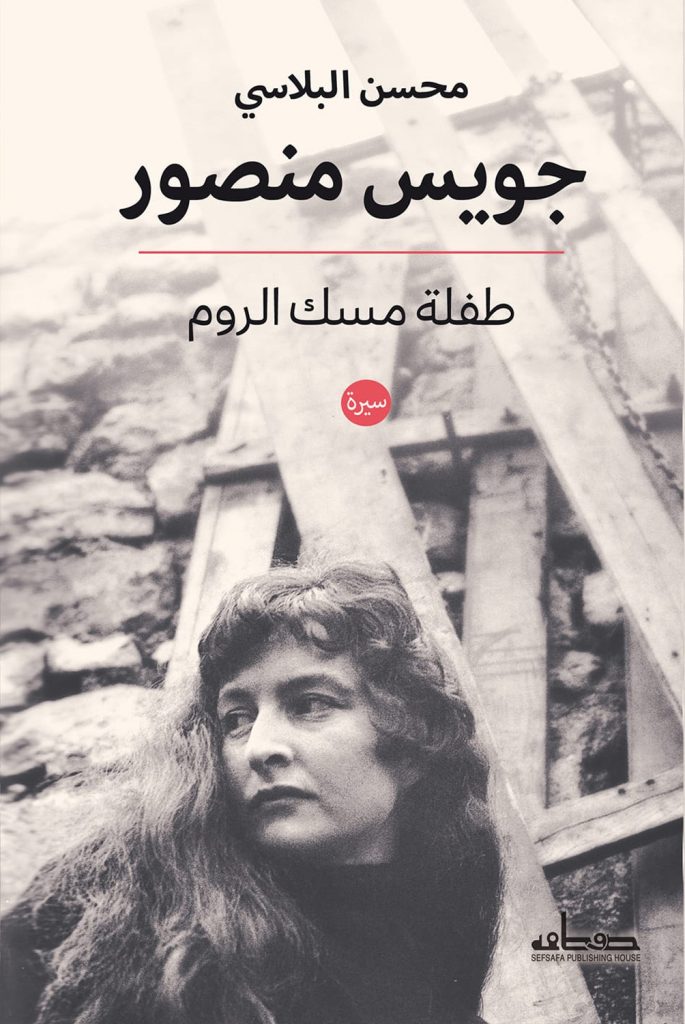

Recently, I wanted to escape from my surroundings, so I read a wonderful book by Mohsen Al-Balasi about the Egyptian surrealist writer Joyce Mansour, whose name always comes up in any discussion of surrealism. It is a biography of Joyce Mansour, her life and creativity, her friends, and the places and times she lived in.

The book is huge, six hundred large-format pages, published by Dar Safsafa. I started reading it and didn’t put it down for almost a week. It is impossible to summarize or cover everything in the book, but I will try to highlight some of the facts that are present and absent in the book.

***

The book has three large chapters, each with sections titled with topics, names of people, and events. The book opens with a quick, expressive statement: “There is a spectrum of lies that occupied Paris in 1986, namely that the garden of delights of this century has died. And that the Eastern tale called ‘The Girl with the Musk Rose’ has come to an end.” Of course, 1986 was the year of Joyce Mansour’s death, and so the book will be a great testament to her life as reflected in her works.

The book discusses and explains how Joyce Mansour was presented to the Middle East only as an erotic poet, and was completely ignored as a short story writer, artist, critic, and surrealist thinker, who participated radically in the formulation and shaping of the international surrealist movement between the 1950s and 1980s.

Thus begins the book. After this introduction, there is a dedication to his wife, the artist Ghada Kamal Ahmed, and to those who supported him in his research or in providing documents and other materials, who will not be forgotten in the book. Then come the introductions to Joyce Mansour: the first is by Will Alexander, the American poet, artist, critic, and musician, who says: “She shone, leaving behind an unparalleled imagination that continues to flourish in our time and beyond.”

***

Another introduction is by Mark Kubig, a researcher at the Sorbonne who has written works on the history of surrealism in Egypt. In Surreal Images, he says: “Who did not love her? And who cannot love her for her transgressions, which are rarely unjustified, always perfectly executed, like a very pointed shoe kicking the backsides of murderers. The woman with the owl’s beard who cradles beneath her mist-filled skirt the endless night and the storm.”

Then there is the introduction by Laurent Dussé, which he dedicates to the artist Ghada Kamal Ahmed, in which he says: “Joyce Mansour is the Sphinx with the head of a falcon… She is the one who captivated Oedipus on the road to Thebes.” Then there is the introduction by Riki Dekornie, the American writer, poet, and artist, in which she says: “Despite the risks, Joyce dares to dance under the scissors of repression and prohibition, reminding us that the incense burner of passionate love (her words) is a world of destruction, intuition, dreams, and deep living.”

Then there is an introduction by Georgia Pavlido, an American poet and artist of Greek origin, who, after talking about her career, says of Al-Blasy’s book: “It is no small feat to be the first book published in Egypt about her. It is more than just a milestone. It is a small miracle.”

(2)

These introductions take your spirit into space to continue discovering secrets and magic. The introduction by writer Mohsen Al-Balasi is about Joyce Mansour, who was born in England in 1928, and talks about the surrealist movement abroad and the position of women within it, and how eroticism became one of the means for surrealists to achieve complete liberation in the face of social fascism.

Orgasm is a small death for the French, and in the 1950s, Joyce Mansour was worthy of Eros, the Greek god of love, and eroticism is an expression of the philosophical and literary aspect associated with sexual desire.

After the death of André Breton, founder of the surrealist movement, in 1966, Joyce Mansour was subjected to a systematic campaign by conservative critics around the world and ostracised by conservative literary institutions and communities in the Middle East. The literary feminist movement also ignored Joyce Mansour because she never approached them. It is said that when she was asked to write for a feminist magazine, she replied, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

***

Talking about the translation of her poems, but here he rediscovers her life and her fictional and critical output alongside her poetry. She did not plan her output in a literal, deliberate way, but her texts invaded her body randomly through her wanderings in a reality driven by objective chance, or through her endless flights of fancy in her dreams.

He talks about the literary salons in Egypt, both foreign and Egyptian, and how downtown Cairo was packed with amusement parks, theaters, cinemas, and dance halls—with historical detail—and he talks about the Zamalek neighborhood, its origins, and the beginning of Francophone activity in Egypt, as well as the French language and its prevalence in literary circles.

All of this was about Joyce Mansour, and she participated in it. Her first language was English, but she gravitated toward French. Her parents were Sephardic Jews from Britain, who held British citizenship due to the persecution of Jews in Europe. They were an aristocratic family, and her father became a businessman in Egypt. She lived in Zamalek as a young teenager, then as a wife and young poet. Egyptian Jews suffered in Egypt after the emergence of fascist groups and parties such as the Muslim Brotherhood and the Young Egypt Party, and they emigrated.

***

This increased in the 1950s with Nasser’s policies, resulting in the mass emigration of thousands of foreign communities. Incidentally, this is the subject of my novel “Amber Birds,” the second part of the Alexandria trilogy. She was the third child of her parents, after her older brother David and older sister Jenny, followed by her younger sister Gillian. Her education and how she was sent to a prestigious girls’ college in Switzerland, where she received a rigorous education alongside dance and music, and mastered operatic singing. She talks about all the places and clubs, such as Zamalek and Al-Jazira Club, in great detail.

In 1945, her mother died of cancer, so she tried to escape the pain by practicing sports, which she became obsessed with. She met Henry Najar, who became her first husband, and they married in 1947, but he also quickly developed a devastating cancer and died. The death of her first husband, when she was still young, was a shock that was clearly reflected in her first collection of poetry, “Screams.”

***

In 1948, a year after the death of her first husband, she met Samir Mansour at the Yacht Club. They married in 1949 and traveled to France and Italy, where she rediscovered happiness at the age of 21. One of the most important literary salons in Egypt was that of Marie Cavadia, the Romanian poet and writer. She talked about her and her poetry, and how the salon was Joyce’s imaginary home, and how the surrealist movement was advancing in the world and in Egypt.

In this salon, writers such as André Gide and Georges Hanine appeared, for whom Marie Cavadia opened her salon and for the surrealists in Cairo, and the exhibitions they held and the magazines they published. Letters from Georges Hanine to Joyce explain how the movement attracted her. Then came the mass emigration of Jews from Egypt in the 1950s, the imprisonment of her father and husband Samir Mansour and their release, and her escape with Samir Mansour to Paris with their two young sons. She was 28 years old. Then her father died of cancer at the age of 76.

In the early 1950s, Joyce Mansour was not part of Egyptian surrealism, despite her participation in some events organized by friends of George Henein, who encouraged her to publish her poems. However, she did not write in Egyptian surrealist magazines. They succeeded in publishing some of her poems in France, and Paris was her new birthplace, where she settled in 1955.

(3)

Since the 1940s, surrealism in Europe had enemies who saw it as utopian, romantic, decadent capitalism, and subversive chaos, while large numbers of young artists and writers were waiting to join the movement. The storm began to subside in the early 1950s.

Joyce participated in most of the Surrealist publications and exhibitions, and her journey was with Georges Honnet and Pierre Segfer. Honnet was a poet, artist, historian, and publisher whose works were closer to Dadaism, and he was close to many of the founders of Surrealism in France. Honne introduced her to his friend, the publisher Pierre Segfer, who published her first collection of poetry, “Screams.” After that, enthusiasm for her grew and her name spread, and there is much written about her in the book.

In 1955, she published the book “Tears.” It discusses each book, the circumstances of its publication, and samples of her poems. The year 1954 was exceptional for her, as her poems appeared in several literary magazines mentioned by the author. Joyce deliberately avoided the upheavals in Egypt following the Free Officers Movement in 1952, and she settled in Paris, where she formed a legendary union with the Paris Surrealist group on a poetic level.

***

Detailed conversations about André Breton, her weekly meetings with him and the Surrealist group, and Breton’s attraction to her, to the charm that emanated from her, the strange young woman with a predatory poetic talent. How her second collection of poetry, “Tears,” was inspired by her feelings toward André Breton. They exchanged letters despite her settling in Paris and seeing him.

They had intellectual conversations about the meaning of surrealist violence and black humor, which challenged bourgeois and patriarchal laws. Joyce’s works are an example of black humor, as André Breton mentioned in the introduction to his book Anthology of Black Humor. Examples of this poetry, as always, and her writing of surrealist short stories, which many people do not know about surrealism, and a discussion of the essence and meaning of her stories and examples of them.

***

A tour with her and the surrealist cafés in Paris and her collection of André Breton’s letters. Parisian cafés had been witnessing the surrealist movement since the 1920s. Examples of this and their movements between them. Café de la Source was for the Dadaists, for example, and then Café Le Cerf became Breton’s headquarters, and there were those who preferred the bar Le Couple or La Cote d’Or.

All the names of the cafés and stories about them. How Joyce and Breton’s hobby was to wander around collecting surreal objects from second-hand shops. And things they discovered on their wanderings, such as a cabinet with carved animal panels and other items. Joyce drew much inspiration for her poetry from the objects she collected.

A discussion of Joyce and eros or sex in her poetry and stories and the poetry of the Surrealists, and how in Joyce’s world there is a connection between eros and death and birth. Conversations and examples as usual, and the opinions of others.

***

Joyce Mansour saw writing as a physical urge, like eating, saying, “I write when I have to, like eating, or when I’m sick, or when I have to go to the bathroom.” Writing is a physical need that is part of our daily experience. He moves on to her narrative, much of which defies classification, and the book ends with a section of her prose narrative. As Feldina said, this has not been highlighted, only her poetic output, while she has a huge output in prose, criticism, and stories alongside poetry. Even translations of her poetry are few and far between.

Despite their eroticism, her writings do not represent mainstream erotic literature, but rather were intended to create an inner liberating energy against the specters of death, illness, and mortality that seem to have inhabited her mind. For example, she has five story collections, such as The Satisfied Sleepers, Julius Caesar, The Boxes, The One, and Harmful Stories. They were published by major publishing houses such as Gallimard, La Soleil Noir (La Soleil Noir), and others.

***

Discussions about each book and its content, and about the Paris exhibitions she attended, such as the International Surrealist Exhibition in 1959 and the Eighth Surrealist Exhibition, among others, with details of the exhibition’s contents and the names of the artists who contributed to it. One of the exhibitions was held in her apartment with Samir Mansour in Paris, and she photographed expressive symbols of the exhibition, such as the surrealist creature from the exhibition held in her apartment, which was created by Jean Benoit, the star of the show, and the interpretation of the symbol.

Other exhibitions abroad, such as the Milan exhibition in April 1959. Her participation in surrealist questionnaires, an old surrealist tradition since the movement’s inception, was the title of one of the questionnaires: “The Position of Painting – When is a Painting Surrealist?” In one of her five answers, she says: “The distinction between magic and the magic of imagination is, for me, sophistry. Art and magic are only artificially differentiated terms, as they use the same means of communication with the constant. Traditional art is active magic and its message.”

She explains how surrealist games are the most important ways to open up the psychological space for creative expression, about her female model and more, and how she was like a new “Alice” in Wonderland.

(4)

She talks about her friends of words and colors, names such as Pierre de Mondrian, and how she became close to him, the French surrealist poet who influenced her, and how they exchanged gifts of texts and models. She had met him before in Cairo in 1955, and he was one of her biggest motivations for settling in Paris.

Likewise, Leonor Fini, one of the most prominent surrealists in the visual arts, who declared herself bisexual, attracted to both men and women, but not a lesbian, as marriage never appealed to her. How could she live with just one person? She used to visit her in Egypt, as Samir Mansour, Joyce’s husband, said. Léonor loved cats, and her apartment was like a Parisian commune for surrealists. She was influenced by ancient Egyptian civilization, as was Joyce.

Then comes the story of Hans Bellmer, the sculptor and painter who read her manuscript Julius Caesar, his letters to her, and how he designed the book cover for her. There are conversations about the book in the building, its meaning, and pages from it. Then comes Pierre Molinier, the visual artist who also wrote poetry, and dedicated a poem to her that you will find in the book.

***

André Breton gave her the nickname “the musk rose child,” and she became famous by that name in Paris. Musk is a beautiful plant with a captivating fragrance. We move forward through the years to the 1960s and what happened after the student movement in Europe and Paris in 1968 and its positive impact on the surrealist movement, which led to the emergence of sexual and artistic liberation movements in various countries. In the 1970s, the Surrealists joined the battle for women’s liberation to support sexual freedom in its deepest erotic form.

This is followed by a discussion of criticism and her view, through criticism, of ancient myths about death, the afterlife, and other topics. Then comes the final chapter, which returns to some of the characters and their visit to Havana after the communist revolution in Cuba in 1968 with artists, poets, and others, and how the revolution in Cuba was initially inspiring to the Surrealists until totalitarian ideas emerged. She recounts the details of this and the artists’ views on it at length.

***

Among those she met and had great friendships with was Pierre Alchiniski, a visual artist, with whom she corresponded and collaborated, such as on her only surrealist play, The Blue of the Boxes, which was published in a magazine and, eight years later, in 1967, was performed in a café with a theater that could seat fifty people. What was said about the play and excerpts from it.

Incidentally, Joyce Mansour played the lead role in Virginia Woolf’s play “Fresh Water.” Her journey to publication in the 1970s, numerous quotations from her texts, and other events led to the loss of others, then the passing of the years and her last dreams until the end in 1986. Cancer, which had previously struck her loved ones, struck her at the age of fifty-eight.

There is a guide to the stages of her journey since birth as a historical record, including her education, countries, exhibitions, meetings, and more. Then there is a bibliography of her works, both published and unpublished. It is a great treasure that deserves to be revived.

***

In the end, the book is a great research and intellectual effort, and I apologize that the article did not have room for many of the letters or pages of stories, poetry, and theater that characterize the research or the images that fill the book.

I leave it to you.

The most beautiful conclusion to the article is what Georgia Pavlido, the American poet and artist, said about it in the introduction: “It is no small feat to be the first book published in Egypt about her. It is more than just a milestone; it is a minor miracle.”