Where Civilizations Converge: Exploring Naqada’s Unique Pharaonic, Coptic, and Islamic Layers

On the west bank of the Nile, across from modern Qena, lies Naqada, a city that predates the Pharaohs themselves. This is not merely a town, but the namesake of the Naqada cultures that laid the foundation for ancient Egypt’s dynastic glory. Here, history doesn’t whisper; it speaks from the very walls. The language is written in the mud-brick of ancient palaces, the intricate carvings of mashrabiya screens, and the symbols adorning doorways: stuffed crocodiles and ram horns placed by generations past to ward off envy and protect the home. Quranic verses and Coptic prayers both adorn house facades, a unique harmony that tells the story of a city that has preserved its spirit for over six millennia. Bab Masr wanders through the streets of this living museum.

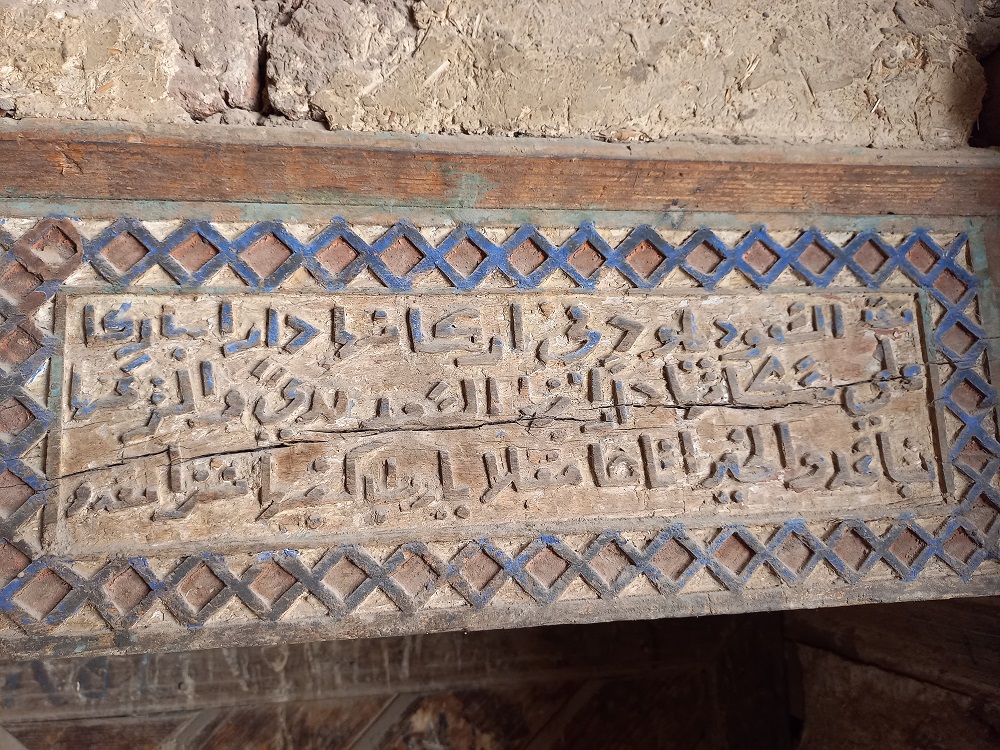

Coptic and Islamic inscriptions

Ahmed Youssef, an Islamic antiquities inspector for Bab Masr, says, “The houses of Nagada, despite their small size and simple materials, mostly made of mud brick, are characterized by a clear artistic touch that reflects the era in which they were built.”

He adds: “During the Ottoman period, the Nagada area underwent extensive renovation of these houses, which was clearly evident on their facades. Black mangor bricks and decorations combining religious and folk motifs were used. Quranic and Coptic phrases and verses were also written on the facades and doorways of the houses, as well as on the windows, doors, and drinking fountains.

The antiquities inspector continues, “During the Ottoman era, six-pointed star decorations and other elements expressing the identity of the homeowner appeared. Coptic houses used the cross as a basic decorative element. In addition, there were Coptic verses from the Old and New Testaments and religious prayers blessing the house, such as:

“Bless this house with blessings and fill it with your goodness,” or short prophetic sayings such as “O you who enter this house, pray for the chosen prophet.” Or sayings engraved on the doorsteps such as: “The safety of man lies in guarding his tongue” and others.

A common feature

The common feature between these houses, whether Islamic or Coptic, is not only their religious content. It is also their simple architectural spirit, which carries a cultural and spiritual depth rarely found elsewhere.

In Naqada, you don’t need books to read history; it is enough to look at the facades of the houses, breathe in the fragrance of the alleys, and listen to the sound of the stones that have kept secrets for thousands of years.

The architecture of old houses preserves privacy

The inspector of Islamic antiquities says: “Between the mud walls and palm-leaf roofs lie hidden stories of the past and the fragrance of authenticity. The designs of these old houses were highly adapted to the climate, providing warmth in winter and humidity in summer.”

He pointed out that when designing these houses in past centuries, architects were keen to preserve the privacy of their inhabitants. They used broken entrances, which were one of the most important elements. These prevent direct visibility from the outside to the inside, enhancing the privacy of the houses.

Small windows were also designed to allow light and air to enter while respecting the privacy of the houses. It is architecture that respects people and harmonizes with its surroundings, providing a model that can inspire today’s architects in the design of modern houses. It takes privacy into account, makes use of resources, and expresses the identity of the place and its inhabitants.

The inspector of Islamic antiquities added that some houses used wooden mashrabiya screens. These are an Arabic decorative element that reflects the Ottoman period and respects the privacy of homes in terms of visibility. They were designed with hollowed-out floral motifs or arabesque patterns.

Another striking detail is the use of door knockers in different shapes that produce different sounds. One was designated for men and another for women, so that those inside could know the gender of the visitor before opening the door. This reflects the precision and awareness of ancient Egyptian architects in taking into account the details of social life in Upper Egypt at the time.

Healthy architecture from the heart of the environment

Youssef adds: The architectural construction of houses in the past took into account the health aspects of their inhabitants. Houses often had an open inner courtyard that allowed for air circulation and sunlight to enter. This helped to sterilize the space and purify the air, and it was decorated with trees and plants that softened the summer heat and gave the space vitality.

Inside the houses, details reveal an early architectural awareness of health and comfort. Sanitary toilets with ventilation openings and a special “chimney” were used to ensure air flow without harming the user, especially during bathing.

He pointed to the use of Nile silt in construction, along with mangor bricks in the decoration of wealthy homes. Stone was used in some facades and decorations, in addition to palm fronds and wood in ceilings and wall connections.

Bridges of communication and empathy

In the alleys of the old neighborhoods, houses were not just walls and roofs sheltering their inhabitants, but living beings pulsating with social and emotional relationships.

One of the most prominent social and architectural phenomena was the shared water well between two or more houses. Bridges or arches connected the houses, not only to facilitate movement, but also to exchange food, conversation, and friendship. Women often passed fresh food or freshly baked bread across these small bridges, in a vivid embodiment of love and generosity.

In narrow, enclosed alleys, the suqifa or sabat became widespread. This was a structure connecting two houses from above, allowing passersby to walk underneath it. Above, it became a meeting place for women in winter, where they would sit in the warm sunshine and chat away from the eyes of strangers. This architectural style was common in the villages of Naqada, which were characterized by the cohesion of their inhabitants and their shared sense of belonging.

Kitchens of the past

Kitchens were deliberately spacious and well ventilated, as they contained natural stoves that burned waste materials and open fires. This required a well-thought-out design to expel smoke and reduce heat, and no old house was without a communal oven. Whether in the courtyard or on the roof, these ovens were used to prepare sun-baked bread, which is part of the traditional diet.

Inside the kitchen was what is known as a “shanata.” This was a wire rack with a wide tin base on which food was placed to prevent it from spoiling. Guest rooms were the preserve of large houses and were often located at the front of the house to preserve the privacy of the family. Some families, however, resorted to setting up public guest rooms as a family custom for receiving visitors and strangers.

Drinking utensils

The image of the old house would not be complete without mentioning the zeer, jar, or qulla, which were natural drinking utensils that kept water cool and pure before homes had the luxury of refrigerators.

Ultimately, it can be said that the old house was not just a shelter, but an integrated social entity, in which the architectural design formed a language of daily communication between people, reflecting the authenticity of a society that lived in solidarity and harmony.

Naqada: Antiquity, Age, and History

Mahmoud Madani, Director General of Antiquities for Upper Egypt, says: “Naqada is an ancient Egyptian city dating back to the beginning of the Pharaonic era. It is mentioned in the first and second Naqada civilizations, which are consistent with the Badari civilization in Asyut, and has pre-Pharaonic human settlements.”

He adds: “It is one of the most important cities in Upper Egypt that still preserves its ancient buildings. It is rivaled in this regard by the city of Esna. Naqada is distinguished by the architectural and heritage richness of its ancient houses. Its current buildings date back between 400 and 600 years. This is evident in most of its buildings and streets, which show signs of age and antiquity.

How was it built?

Its buildings were constructed from mud bricks or adobe, mixed with red lime, plaster, or clay. They are plastered on the outside with a layer of clay or a mixture of straw.

The director of antiquities adds that what most distinguishes the old houses is the presence of founding texts written on the wooden lintels at their entrances, a tradition dating back to the Pharaonic era. The ancient Egyptians documented their lives by inscribing them on the walls of temples, and these texts serve as a reminder of the founding of the house, noting that there are more than 200 texts written on the doorsteps.

This bears witness to an important period in the history of the city and the surrounding villages. In addition, some of the entrance blocks are decorated with red or black mangor bricks and cream-colored marble or limestone, taking advantage of the color contrast between the stone and brick in geometric patterns on the doors to decorate the facade. This indicates the wealth of the homeowner.

Details of ancient architecture

Madani points out that in that era, houses were characterized by the presence of mashrabiya, or carved wooden screens on windows, due to the narrow alleys and lanes at that time. This led to the houses being exposed to each other. Therefore, mashrabiya and high balconies were used to block the view inside the house. Winged animals and other figurative shapes were also used to decorate doors.

Coptic text on a house renovated 200 years ago

During filming, Madani read a text written on the ornate wooden lintel of one of the old houses, which was renovated about 200 years ago. It read: “The head of wisdom is the fear of God, and the beloved son pleases his father. Happiness and long life in glory, honor, joy, and the passage of time and ages. This house was renovated by Gerges and Gerges, sons of Andraos Petros, 1640 Coptic.”

He explained that the house was very old and had been renovated more than two centuries ago. It was later used as a large and well-known oil press, but it was closed in modern times.

He pointed out that it was common architectural practice at that time for houses located at street intersections to be built with a corner column with a space for lighting to facilitate the passage of pedestrians due to the narrowness of the streets. In the past, the locals respected the right of way and built their houses on the upper floors.

Toukh… one of the historic villages

One of the ancient villages in Naqada is the village of Tookh, which means “the western path” because it is located on the west bank of the Nile. It is characterized by its ancient buildings, palaces, and mosques, with the ancient mosque located in the heart of the village, surrounded by palaces and old houses, most notably the palace of Mayor Nashat, who ruled the village in the last century.

Mayor Nashat’s Palace: The most famous palace in Tookh

Mayor Ayman Nashat, son of the palace’s owner, says that the palace was founded by Muhammad Abdallah Bek, his father’s grandfather, and dates back to the beginning of the last century. It was built on a large area in the village of Tookh, south of Qena Governorate, and consists of three floors with a palm leaf roof, each floor comprising eight rooms.

The first floor contains a lounge, a salon, two balconies, and another back door. The palace walls still display a number of commemorative photos, including one of his grandfather with the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Ayman explained that the palace has a large garden covering an area of about 8 acres, which was planted with various fruit trees, and that the palace was the seat of the Umudiyya until his father’s death several years ago.

Dr. Salah Batouk’s Palace

The village also includes Dr. Salah’s palace, located in the center of the village, which is characterized by its ancient ornate doors and Corinthian columns, and is predominantly white and brown in color. The village also includes a number of other palaces built in the same traditional style.

Al-Khatara Village

One of the oldest villages in Naqada is Al-Khatara, which overlooks the western side of the Nile and is opposite the sugar and paper factories in Qus on the eastern side. There you can see the palace of Mayor Yasser, which preserves simple family possessions. The palace still stands today and is preserved by the family as a private heritage site. It consists of two floors, decorated with long windows, an old wooden main door, and a ceiling surrounded by decorative wooden paneling. It includes a number of rooms, including two large guest rooms.

In the center of the village stands the ancient mosque, distinguished by its towering minaret, which reaches a height of about 40 meters, and includes an old pulpit dating back to the mosque’s founding at the beginning of the last century. The minaret has narrow stairs made of mud and stone, which are dark when climbing, but from the top you can see the east and west, where the cities of Naqada and Qus and all the surrounding villages appear.

Mahmoud Alian, one of the village’s residents, says, “The village is old and has very ancient houses, some of which are closed, but it still retains its authentic character. Some of them also have barns that were used for agricultural production and rooms for storing grain, as the village is famous for agriculture.”

Pigeon towers: architectural artifacts

Ahmed Abdallah adds that the story of the towers and the area in which they were built is as old as the buildings themselves, noting that this area was formerly known as “the difficult land” because it was elevated above the rest of the land so that it would not be flooded by the Nile.

Given that the locals worked in agriculture and needed organic fertilizer from animal and bird manure—including pigeons—the idea of building these towers came about. Abdallah continues that the method of building the towers was unique, as they were built above houses, either on the first or second floor, while the lower floors were used for living or as a place to raise livestock.

The towers were built using mud bricks and palm trunks, with clay openings in the walls for the pigeons to enter and smaller openings for ventilation while the birds were in their nests. He adds: “The towers were used in two ways: the first was economic, for raising pigeons and selling them or consuming their meat, and the second was agricultural, for using their waste as fertilizer.”

At that time, mountain pigeons were the most common, as domestic pigeons were not yet widespread, given that most of the towers were in uninhabited areas. These houses date back to 1870, the year in which the houses of the Naja Dobi area in Al-Khatara were built.

Kom Al-Daba

Kom Al-Daba is one of the ancient villages dating back to the first and second Naqada civilizations. At its heart is the Handicraft House, an art workshop where women who make “farka” produce hand-woven fabrics and carpets, distinguished by their quality and natural artistic touches.

Abdullah points out that about ten years ago, the village had a large number of old houses with wooden lintels carved on their facades, but most of them were demolished, and only a few remain today. There is also only one pigeon tower left, as most of the towers in the village have been removed.