Hossam Fakhr’s The Other Stories: Heritage and Postmodernism in the Story Factory

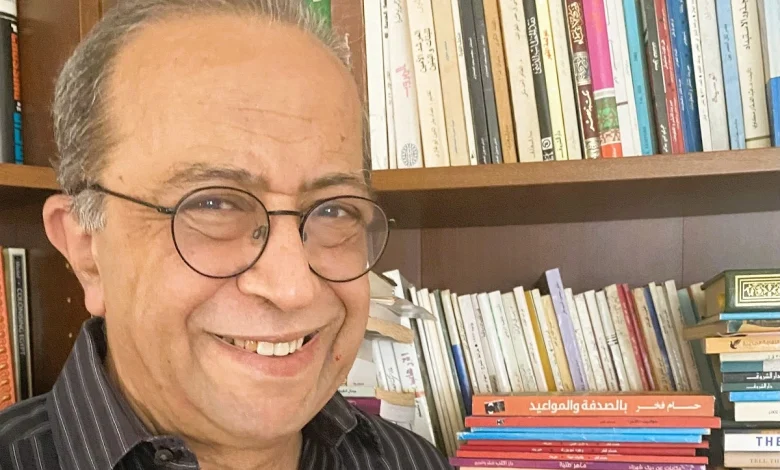

I became familiar with the work of writer, novelist, and translator Hossam Fakhr when I first read “Amina’s Stories,” followed by “By Chance and Appointment” and “The Tongue of a Bird.” But Fakhr himself drew my attention to his different work, “Hawadit al-Akhar.”

This work took me into a mixed world, a world where postmodernism intersects with the tales of One Thousand and One Nights; the harsh world of “The City of Copper,” where souls are uprooted, and worlds of fantasy and strangeness resist this world and its endless cruelty. This literary work, which combines a single theme with several short stories, belongs to what is known as a “short story cycle.”

In this genre, the stories form an integrated whole; it is not a traditional novel with a linear narrative, but rather a collection of interrelated tales revolving around one or more characters, brought together by a single narrative structure, in which the narrator’s voice intertwines with the stories of “the other.” Thus, we encounter this narrative thread through the characters of the narrator and “the other.”

The framework of the story: One Thousand and One Nights in the modern era

The writer has drawn heavily on his rich and diverse cultural background, using a style reminiscent of the intertwined narrative structure of One Thousand and One Nights. In the work, the “other” plays the role of Scheherazade, who tells the stories, while the writer plays the role of Shahryar, who listens to and records these stories.

The narrator and the narrative framework: The story begins with an encounter between the writer and “the other.” “The other” climbs onto the writer’s shoulder and dictates stories to him, giving him a reason to write. This framework closely resembles the relationship between Shahryar and Scheherazade, where the narrative continues to ward off danger or achieve a goal.

Narrative language: The writer uses rich language in a narrative style that tends toward the oral and colloquial, employing popular proverbs and idioms such as: “O noble gentlemen,” “It is as if we, O Badr, neither went nor came,” and “The messenger is only responsible for the message.” These elements give the text an authentic feel and remind us of folk storytellers and the atmosphere of One Thousand and One Nights.

The City of Copper: From Myth to Modern Metropolis

The “City of Copper” in the novel is not just a place, but a central character and a powerful symbol. It represents modern Gharbia civilization, dazzling with its technological progress and wealth, but hiding coldness and isolation behind its facade. It is a city of strangers that attracts them with its promises, but quickly imposes its harsh laws on them and robs them of their identity and souls.

Here, a clever and interesting intertextuality emerges, not only with the traditional myth of the “City of Copper,” but also with Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis (1927). Both cities, the city of pride and Lang’s city, share the symbolism of absolute power and scathing social criticism.

The sharp class divide: This is the most striking similarity. In Metropolis, society is starkly divided between the class of thinkers and rulers who live in paradise above ground, and the class of hard-working laborers who live and work in hell below ground. Similarly, the City of Copper in Hawadit al-Akhar is a city ruled by money, where an individual’s fate is determined by the number of “pennies” they have, and its protagonist, “the Other,” lives in menial jobs and is exploited.

Beauty that hides danger:

From the outside, “Metropolis” appears to be a utopian, futuristic city, but this beauty hides oppression and exploitation. Similarly, “The City of Copper” is a dazzling city that attracts Gharbia with its promises, but in reality it is a “one-way street with no return,” a cruel city “where souls are uprooted.” .

However, the fundamental difference is that Metropolis ultimately offers a solution, where the “heart” becomes a mediator between the ‘mind’ and the “hands.” The City of Copper in Hawadit Al-Akhar, on the other hand, seems hopeless and without salvation; it is the physical embodiment of the concept of inescapable alienation.

The voice of “the other”: the echo of the immigrant intellectual

The “other” represents the symbol of the Arab intellectual immigrant who faces an existential conflict between his original identity and Gharbia culture. This conflict is embodied in small but profound details: his mother tongue, which he has almost forgotten but feels a love for when he speaks it, and his constant sense of alienation and loneliness. His stories are not mere fantasy, but metaphors for real crises:

In “The Tale of Bread and the Sword,” ‘the other’ is forced to repeat meaningless words in order to survive, a harsh reference to the loss of authentic expression in a foreign society.

In “The Tale of the Trial and the Long Prison,” the crisis of alienation reaches its surreal climax, as his soul is surgically removed and imprisoned, while his body is set free. This pivotal story is a scathing critique of a materialistic society that prioritizes the productive body over the free spirit, depicting the absolute disintegration of the protagonist, who is physically free but existentially imprisoned.

The incident of the “attack of the birds” on the “tall towers” is a clear reference to the events of September 11, and how fear became the new “ruler of the city,” highlighting the “other’s” feeling of absolute loneliness even in the midst of a collective disaster.

Creativity that transcends the artist

In the end, the stories conclude by revealing that the “other’s” greatest struggle is with his “deadly love,” a self-destructive addiction. Here, the narrator (Shahryar) changes his stance; after expressing his hatred for “the other,” he feels deep sadness and admits that he loved his stories, begging him not to let this addiction end the narrative.

This ending is a confirmation of the value of art and creativity. The stories transcend the artist’s flaws and become what remains. The Tales of the Other is not just a series of stories, but a testament to the power of storytelling in the face of a cruel world, and a call for the artist to resist his demons for the sake of his art. Hussam Fakhr has succeeded in creating a postmodern work with roots in tradition, a work that raises painful questions about identity, alienation, and salvation in a world that has lost its soul.