Baligh Hamdy: A brilliant beginning and a dramatic end

His name was Baligh Abdelhamid Hamdy Morsi. He was born on October 7, 1932, on Tawfiqia Street in Rod al-Farag, in the historic Shubra neighborhood, and died on September 12, 1993, at the Gustave Roussy Hospital in France. Between his birth and death, he lived a long life filled with music and melodies… but also pain.

His father was the scientist and writer Dr. Abdel Hamid Hamdy Morsi. Baligh said of him: “My father was a natural scientist specializing in optics, and he had many publications. In addition, he was very interested in music, played the piano, had a beautiful voice, and was one of the first music enthusiasts in Egypt. He almost became a professional singer, but my grandfather quickly sent him to London on a scientific mission to complete his studies in natural sciences, which meant cutting short his singing career. Among his friends were Zakaria Ahmed and Al-Qasabgi, who used to visit him at his home, where he held gatherings for listening and singing.”

A cultural home

His mother was Aisha, or “Mama Aisha” as Baligh called her. She was well-educated and fiercely loyal. She wrote poetry in praise of the leader of the nation, Saad Zaghloul, and was an active member of the Wafd Women’s Association.

Baligh said of her: “I remember that my mother would not let us go to school if it rained, which rarely happened in Cairo. This made me feel her fear for us and her love for us, and I loved her more than she loved me. Whenever I saw a black cloud in the sky, I would rush to my mother from wherever I was and say to her, ‘Come on, Mama, it’s going to rain.“ Then I would take her by the hand to the room and take shelter with her… and she would take shelter with me.”

The fourth child

Baligh was the fourth of five siblings: the eldest was Dr. Morsi Saad Eddin, a prominent writer and journalist and one of the most prominent writers for Al-Ahram newspaper, who was like a father to Baligh after his father’s death. His sisters Safia and Asma were both amateur painters, and Safia worked for a time as a fashion designer and journalist for Al-Jil magazine. She was deeply saddened by Baligh’s passing and followed him only 40 days later. The youngest sibling was Hossam, an army officer who died young due to heart disease.

Education

Baligh obtained his primary school certificate from the Hoda Shaarawi School in Shubra in 1946. His neighbor was the great poet Salah Jaheen, who recounted his memories of him: “This was in Shubra in the early 1930s. Cairo was filled with music and melodies. Among the musicians I also met during that important historical period, they warned us, ‘Who? Baligh Hamdy, we were children, still being carried from place to place by others.

Our families lived in two adjacent apartments, so if our mothers wanted to drink a cup of coffee together, they had to put us on the floor in a corner of the room. That way, they could chat in peace without fear of us falling and hurting ourselves. I was a few months older than Baligh, and of course I didn’t spare him. I would hit him, pinch him, and poke him in the eyes. It’s true that he would bite me in self-defense, but I always won, simply because of the age difference, of course. I have only one request: please don’t think that this is the reason why Baligh has not composed any songs for me until now. He has a pure heart and could not possibly have held a grudge against me all these years!

Three schools

In the following stages, Baligh moved between three schools: Nile, Prince Farouk, and Tawfiqia. After obtaining his high school diploma, he wanted to enroll in the Arab Music Institute, but his mother insisted on law school, so he enrolled there, and at the same time enrolled in the Higher Institute of Musical Theater (evening classes).

He remained a student at the Faculty of Law for many years without obtaining his bachelor’s degree because he was preoccupied with art, and he postponed his exams every year until he died before obtaining his bachelor’s degree.

At the institute, he studied solfège, music notation, acoustics, and harmony under Kamal Ismail, until he reached the stage of “contrapoint,” or reverse melody, which is an advanced stage in music theory. He also studied Andalusian muwashahat and memorized many roles and folk melodies.

His start with music

Baligh said: “A long time ago… a very long time ago, I was six years old, as I recall, and my only hobby was listening to the radio. We had an old piano at home, which came with my mother’s dowry, as was the custom. My father hired a teacher to give my sisters Asma and Safiya piano lessons, but I was the one who learned, not them. My father recognized my talent and encouraged me to listen to classical music, which I hated at first because of my age.

But my father made me sit next to him once a week to listen to international symphonies, in addition to encouraging me to listen to Arabic songs. Music did not distract me from my studies until high school, when I enrolled in law school and the Fouad I Institute of Arabic Music. There, Dr. Al-Hafni, the father of Rateba Al-Hafni, heard me and transferred me to the Higher Institute of Theater Music.

He adds: ” There was a reason that motivated me not to neglect my studies, and that reason was that I was determined to fulfill my mother’s wish for me to obtain a law degree so that no one could say she had not raised me well after my father’s death. In addition, I wanted to quench my thirst for music by studying it at the most prestigious institutes, which would have made my father happy if he had lived.” .

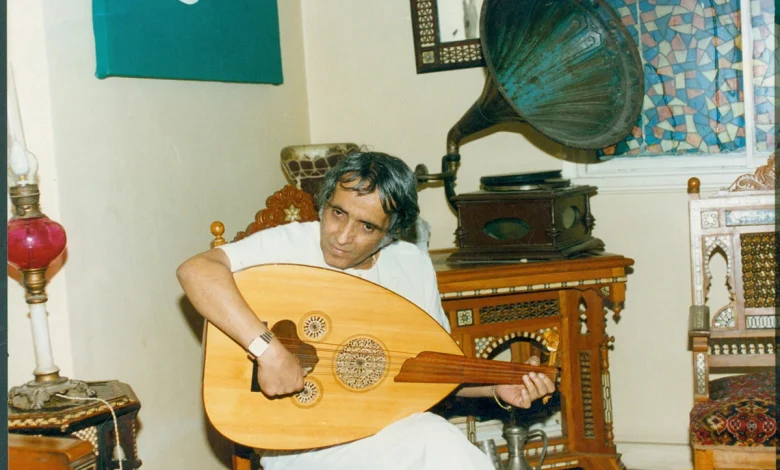

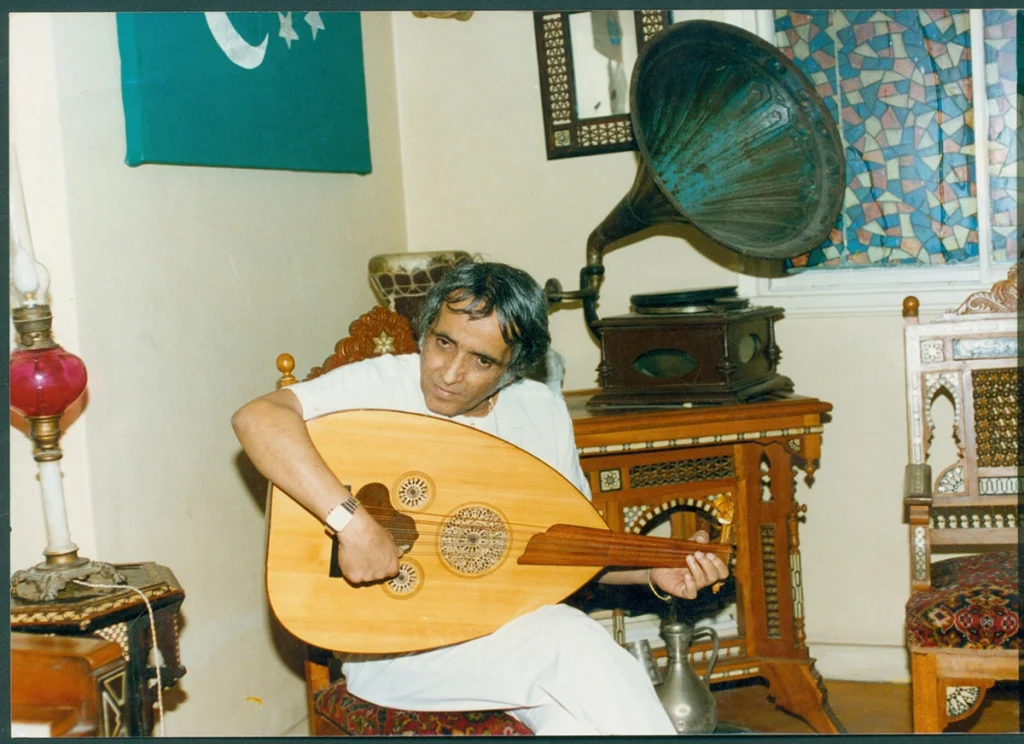

Baligh Hamdy, singer

Baligh met a group of friends at Al-Tawfiqia Secondary School, namely: Lutfi Abdelhamid, Youssef Aouf, Mohamed Awad, Salah Aram, and Samir Khafagi. They were called “the lost gang” because all of its members were veterans of school, having failed many times due to their attachment to art. From this gang, the band “Sa’a Likalbik” (An Hour for Your Heart) was formed, which achieved great fame.

In his early days, Baligh sang songs composed by others, and sometimes he composed some of the music himself. However, his ambition was greater than just being a singer in a radio band, so he decided to knock on the door of the radio station to audition his voice. The decision-maker at the radio station at the time was Mr. Mohamed Hassan Al-Shuja’i, who was impressed by his voice and agreed to approve him as a singer. However, Baligh insisted on being classified as a composer rather than a singer, but Al-Shuja’i adamantly refused.

First radio appearance

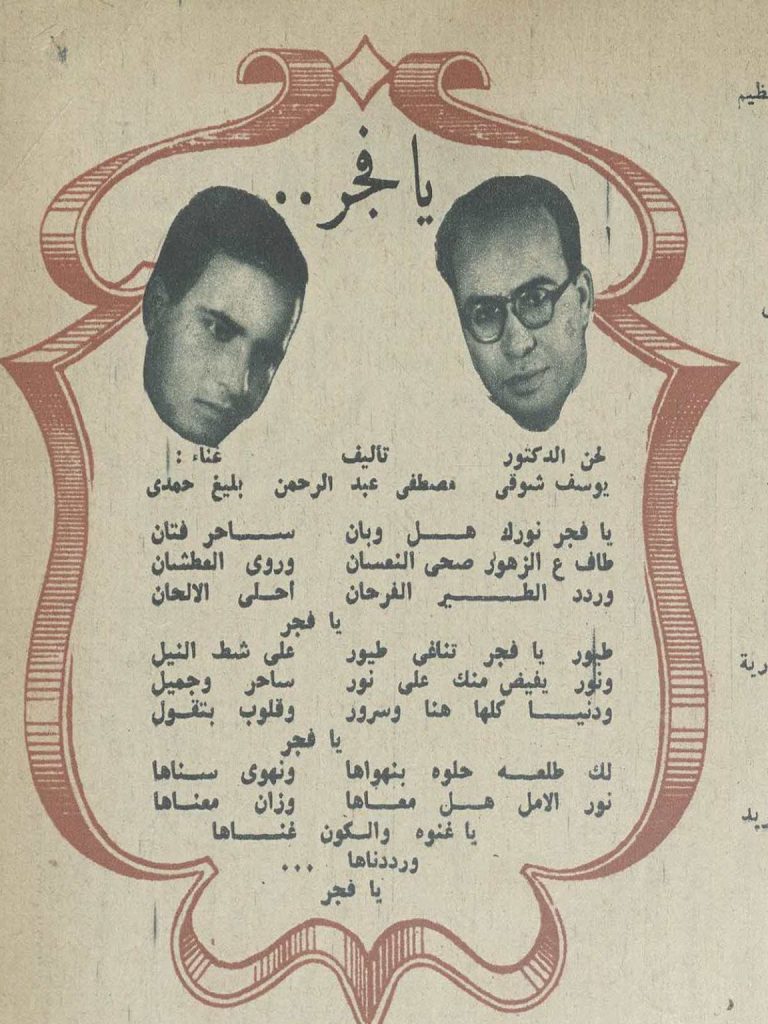

The general program on Egyptian radio introduced Baligh Hamdy to listeners as a singer for the first time on April 25, 1955, with the song “Al-Tayr Al-Asheq” (The Loving Bird), with lyrics by Mustafa Abdel Rahman and music by Dr. Youssef Shawky. Just two days later, on April 27, 1955, a second song was broadcast, entitled “Ya Fajr” (O Dawn), with lyrics and music by the same duo.

O dawn, your light is enchanting and captivating

It has spread over the flowers, awakening the sleepy and quenching the thirsty

And the joyful bird echoes the sweetest melodies

Al-Izaa magazine published the lyrics of the song along with the first photo of Baligh in the newspapers, in issue 1057 published on June 18, 1955, marking his first appearance before the public. More than two weeks later, Baligh participated in the singing program “Qarya al-Jinn” with Karam Mahmoud, Madiha Abdel Halim, and the group, which was based on the poetry of Ahmed Shawqi and the music of Youssef Shawqi, and was broadcast on May 14, 1955.

He then disappeared for about eight months before the radio returned to present him with the song “Ya Layl Al-Ashiqeen” (O Night of Lovers), with lyrics by Mohamed Fathy Mahdi and music by Abdel-Azim Mohamed, which was broadcast on January 15, 1956.

The song begins with the following lines:

O Night of Lovers, have mercy, have mercy My beloved, why are you so cruel to him?

O night of lovers, my heart was empty, happy in my world before I became preoccupied.

It was followed by four other songs:

- “If My Heart Were Empty” (music by Raouf Dhahni, lyrics by Ahmed Helmi) was broadcast on January 21, 1956.

- “O you who weep from the sorrow of days” (composed by Fouad Helmy, lyrics by Zarif Al-Sweifi) was broadcast on February 1, 1956.

- “I no longer believe your promises” (composed by Mohamed Qasim, lyrics by Mohamed Fathy Mahdi) was broadcast on June 22, 1956.

- “Like These Two Days” (composed by Mohamed Omar, lyrics by Abdullatif Al-Basyouni) was the last song he performed on the radio as a singer.

Thus, his record as a singer on Egyptian radio consisted of eight songs, which Baligh felt lacked the ingredients for success, so he decided to change course and give up singing.

First melody

The real turning point for Baligh Hamdy came through the singer Fayda Kamel, his colleague at university and in “Sa’a Likalbik” (An Hour for Your Heart). One day, she heard him singing a song he had composed entitled “Leh Faytni Leh” (Why Did You Leave Me), and she liked it and asked to sing it herself. Baligh welcomed the request, and after recording it, the song became a huge success. It was broadcast for the first time on Thursday, November 1, 1956, less than five months after his last song as a singer.

The song’s success prompted Professor Al-Shuja’i to contact him and invite him to his office, where he said, “I heard your compositions and liked them. Look, my son, I sensed your musical talent, but I didn’t want to push you into becoming a professional before I was sure that you had studied music properly.”

Beligh recounts that period: “Al-Shuja’i paid great attention to me. He believed that music conservatories did not give their students what they needed, so he sent me to Professor Minato to teach me music theory and to Professor Julia to deepen my piano studies. But what benefited me most was my exposure to the artistic and literary milieu of the time, where I learned from Zakaria Ahmed, Mohamed Fawzi, Al-Qasabgi, Anwar Mansi, and Abdelghani Al-Sayed. From Kamel Al-Shinawi, I learned the history of Arabic literature, and from Abdelrahman Al-Khamisi, the art of the short story.”

With national events

The radio program “Leh Faitni Leh” came along with the tripartite aggression against Egypt (1956), and he responded eloquently to the events and began his national career. He presented three songs during the aggression:

- “Nashid Ya Allah Ya Khawya… Ya Allah Ya Ammi” (sung by the choir).

- “We Will Fight” (sung by Huda Sultan).

- “In the Name of the Free” (sung by Karam Mahmoud).

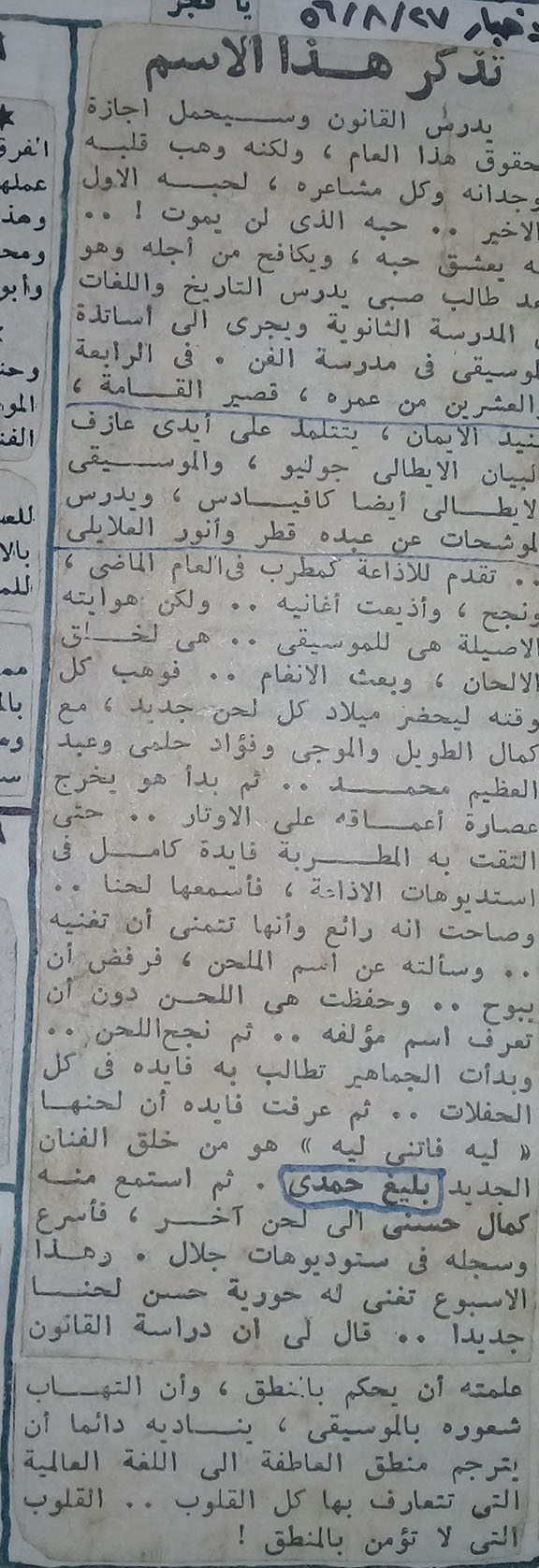

The first article about him

On November 27, 1956, the newspaper Al-Akhbar published an article entitled “Remember this name,” in which the author predicted a bright future for Baligh Hamdy, who at the time had only a few melodies to his credit. Nevertheless, the article—with keen insight—was able to foresee a great future for this young man. It read:

“He is studying law and will obtain his law degree this year, but he has given his heart, soul, and all his feelings to his first and last love, a love that will never die: he adores his love and fights for it while still a student studying history and languages in high school and running to music teachers at art school.

Online art courses

At the age of 24, short in stature but stubborn in his faith, he studied under Italian pianist Giulio and Italian musician Cavades and studied muwashahat under Abdo Qatari and Anwar Al-Alaili.

Last year, he auditioned for the radio as a singer, was successful, and had his songs broadcast, but his true passion is music. It is to create melodies and compose tunes. He devoted all his time to the birth of each new melody with Kamal al-Tawil, al-Mouji, Fouad Helmi, and Abdel-Azim Muhammad. Then he began to extract the essence of his soul on the strings until he met singer Fayda Kamel in the radio studios. He played her a melody and she exclaimed that it was wonderful and that she wished to sing it. When she asked him the name of the composer, he refused to reveal it, so she memorized the melody without knowing its author. The melody was a success, and audiences began to demand that Fayda sing it at every concert. Fayda then learned that the melody “Leh Fatni Leh” was the creation of the new artist Baligh Hamdy.

He then presented another melody to the singer Kamal Hosni, who recorded it immediately at Jalal Studios. This week, Houria Hassan will sing a new melody for him. He told me that studying law taught him to rely on logic, and that his passion for music always calls on him to translate the logic of emotion into the universal language that all hearts understand… Hearts that do not believe in logic.

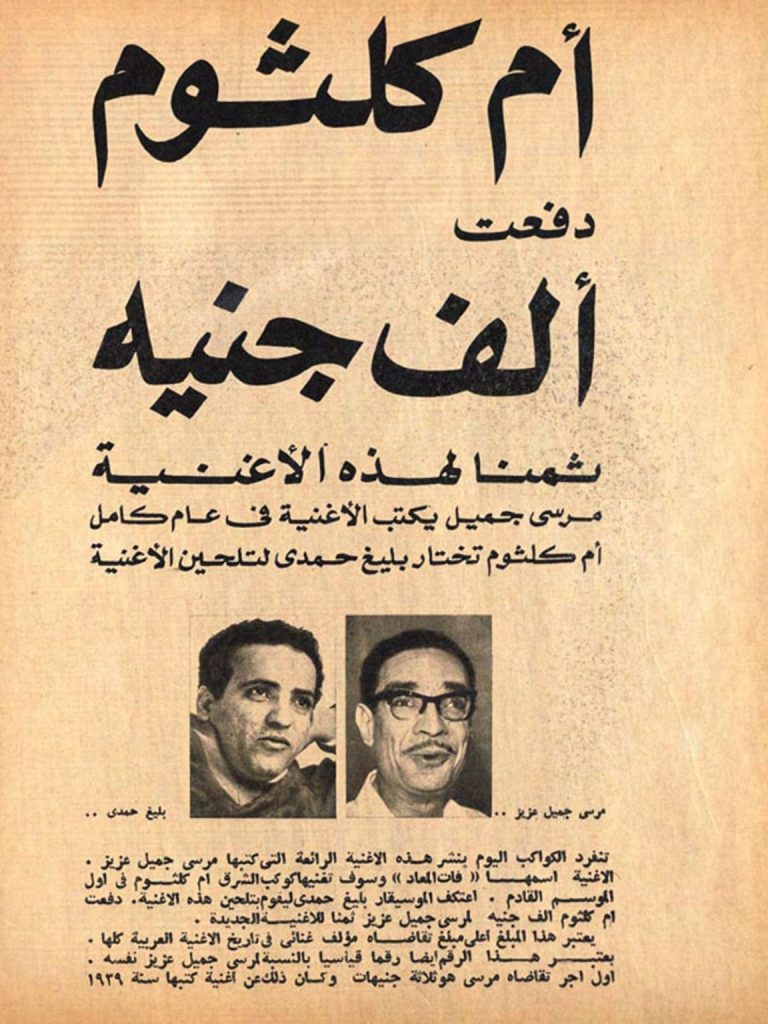

The journey to glory and the first meeting with Om Kulthum

When Baligh’s star began to shine in the sky of melodies, Om Kulthum asked to see him. The meeting took place at the home of Dr. Zaki Suidan, and the evening included the well-known violinist Anwar Mansi, the poet Mamoun Al-Shanawi, the singer Abdelghani Al-Sayed, and the musician Mohamed Fawzi, who arranged the meeting.

That night, Baligh sang the opening lines of a new song that had not yet been set to music, with lyrics written by a young poet named Abdel Wahab Mohamed, who worked as an employee at a petroleum company. The opening lines read: “What is this love you speak of?” At the end of the evening, Om Kulthum whispered in Baligh’s ear, who was only 28 years old:

- Come to my house tomorrow morning!

In the morning, Baligh went with only one thought in mind: that Om Kulthum wanted him to compose a song for her nephew, Ibrahim Khaled, who was thinking of becoming a professional singer at the time. Indeed, Om Kulthum spoke to him about her nephew, and then asked him to play her the melody he had sung the night before. After listening to it, she asked him:

- Whose words are these?

- They are by a poet friend of mine, an engineer at Shell, named Abdel Wahab Mohamed.

- Do you remember the rest of the song?

- No… but let’s talk to Abdel Wahab.

Baligh got up and asked for Abdel Wahab Mohamed, who couldn’t believe his luck either.

From that day on, Baligh became associated with Om Kulthum, and she sang her first song for him on Thursday, December 1, 1960, which was “Habba Eh” (What is Love?).

The song’s success

Kamal Al-Mallakh wrote about the song’s success in his column “Without a Title” in Al-Ahram: “At dawn, I listened—along with millions of others—to Om Kulthum’s new song, ”Where Are You and Where Is Love?” Om Kulthum was at her peak as she sang the melody, her voice like a new musical instrument added to the music. Simply put, it was the most wonderful time I ever listened to Om Kulthum, who yesterday, with her song, wrote two new birth certificates for its composer Baligh Hamdy and its author Abdel Wahab Mohamed.“

The success of ”Hab Eya” doubled Baligh’s credit in the Egyptian music market, after Om Kulthum accepted him as a composer in her musical world. He preceded great composers such as Mohamed Abdel Wahab, whose first meeting with Om Kulthum took place in 1964, while others such as Mohamed Fawzi, Farid al-Atrash, and Mahmoud al-Sharif were not so fortunate.

From that time on, Baligh decided to live near Om Kulthum. He was living in Shubra while she was in Zamalek, so he rented an apartment at 34 Bahgat Ali Street, which became his creative sanctuary. He would sit there for hours composing his melodies, until the residents of the area named the square opposite “Beligh Hamdy Square.” After his marriage to the artist Warda, he rented a second apartment for her in Sphinx Square, while keeping the apartment next to Om Kulthum’s villa as his workplace.

Baligh Hamdy’s compositions for Om Kulthum

Baligh Hamdy composed eleven songs for Om Kolthum, starting with “Habba” (1960) and ending with “Hukm Alayna Al-Hawa” (1973), which she was unable to perform on stage due to her illness, so she only recorded it for radio. Of his memories with her, he said: “There were no serious disagreements between us, everything went smoothly. For example, I would write a high note and she would object and say, ‘My son, I sing on stage and I repeat this a lot, I hope you don’t put it in the high note.

Om Kulthum was not rigid; she accepted new ideas that she felt would add to her art. In the song “Sira al-Hob” (The Story of Love), she had the idea of using an accordion. I brought Farouk Salama and had him memorize the melody at my house. Om Kulthum was very surprised when she found Farouk carrying the accordion and entering the rehearsal without warning, so she said to him:

- Come here, my son. Who are you and where are you going?

Farouk was flustered, and I didn’t know he had come, so I quickly said to her:

- I brought him so you can hear the solo.

- She said: My son, he plays the accordion. What will he do with me?

- Listen to him, and if you don’t like him, he can leave and we’ll cancel the solo.”

When she heard him, she liked him very much and decided to keep him. This was the beginning of the innovation I introduced into Om Kulthum’s melodies.

Baligh… The End

Throughout his career, which spanned from 1955 until his death in 1993, Baligh left his mark on every singer he worked with. He was a partner in the careers of singers of all generations, from Om Kulthum to Ahmed Adawiya, from Abdel Halim Hafez to Ali Al-Hajjar and Hani Shaker, and from Sabah, Warda, and Afaf Radi to Mayada Al-Hanawi, Najat, Aida Al-Sha’ir, Shadia, Latifa, Safaa Aboul Saud, Nadia Mostafa, Maha Sabri, Maher Al-Attar, Mahram Fouad, Mohamed Rushdi, and others. According to the Society of Authors and Composers, he composed 1,359 melodies.

But the end was dramatic. Just as legends love noise and refuse to live quietly, the famous suicide incident in his apartment on December 17, 1984, turned the world upside down. On February 10, 1986, the court of first instance sentenced Baligh Hamdy to one year in prison with labor, a bail of 1,000 pounds to suspend the execution, and placed him under police supervision for a period equal to the duration of the sentence.

The tragedy of Baligh Hamdy

About a month earlier, the tragedy of Baligh Hamdy was the subject of a lengthy conversation between journalist Mahmoud Awad and musician Mohamed Abdel Wahab. At the time, Awad was serving as editor-in-chief of Al-Ahram newspaper, which he considered an inspiring experience and a new professional challenge. Indeed, Al-Ahram’s circulation rose from 30,000 copies to 160,000 copies. Amidst these successes, Mahmoud Awad received warm congratulatory calls about his new venture, foremost among them a call from musician Mohamed Abdel Wahab. Awad seized the opportunity and asked Abdel Wahab to write an article in his name and publish it in the newspaper.

Abdel Wahab paused for a moment before asking him: Are you serious? Okay, I agree… but of course, you’re the one who will write it for me.

Awad replied:

Yes… I will write it for you based on our discussions. Don’t you think that Baligh Hamdy is being treated unfairly? And that the press is to blame? And that the tragedy that has occurred should not make people hard-hearted towards Baligh, because he is also a victim? And that the ongoing and escalating campaign is much bigger than Baligh and encompasses all of Egyptian art?

Abdulwahab interrupted him, adding:

But…!!

Awad replied before he could finish:

Yes, there is a lawsuit going through the courts, but the article I am suggesting you write will not mention it at all. Even Baligh Hamdy’s name will not appear in it. We will only discuss the value of the artist, the value of Egypt, the responsibility of society, the meaning of giving, the danger of schadenfreude, and the crime of sensationalist journalism. With the intelligence of the Egyptian reader, everyone will know that you are talking about Baligh.

Abdel Wahab agreed to let Mahmoud Awad write the article and publish it under his name. Mahmoud Awad wrote the article and read it to Abdel Wahab word for word before publishing it.

I complain about the press

The new issue of Al-Ahram newspaper was published on January 13, 1986, with a reference on its front page to Mohamed Abdel Wahab writing an article for the first time.

The article was titled: “I complain about the press… to the press,” in which he said: “When some people exaggerate the behavior of this or that artist beyond what is reasonable, and when some people constantly judge all Egyptian artists for one reason or another, they are not only diminishing the status of art and artists, but they are also—often unconsciously—placing more obstacles in the way of Egyptian artistic leadership in the Arab world. There are countries we all know that are willing to spend millions upon millions to gain some of this Egyptian leadership in the Arab world. Let us not, out of good intentions, provide ammunition that will immediately be used against Egypt and all Egyptians.

Online art courses

Mahmoud Awad wanted this article to ease some of the pain of the attacks Baligh was subjected to in the newspapers during his trial. When Baligh sensed danger approaching, and at the same time began to suffer from symptoms of liver disease, he chose to travel to London and from there to Paris, where he owned an apartment, and his lawyer filed an appeal against the verdict.

After about five years in exile—which Baligh described as equivalent to a million years in terms of its weight and bitterness—he returned to his homeland three months before the statute of limitations expired. He returned to Cairo on November 24, 1990, and the next day, the Criminal Chamber of the Court of Cassation issued a ruling in his presence acquitting him of that unjust charge and overturning the ruling issued by the Agouza Magistrate’s Court, ending the long nightmare he had lived through, for which he had paid a heavy price.

However, Baligh did not return to his former self after the case. Unfortunately, it was the beginning of the end for him. When his illness worsened, he traveled to Paris for treatment at the Gustave Roussy Hospital, where he died on September 12, 1993. His will was to be buried next to his mother.