Egypt Recovers Looted Antiquities from Australia and U.S. in Major Smuggling Bust

Egypt has recovered a trove of stolen antiquities from Australia and the United States, unveiling new details of an international smuggling network that for years trafficked artefacts looted from tombs and official storerooms. The investigation exposes how a single criminal group allegedly used forged documents, online auctions, and a web of dealers to launder Egypt’s heritage onto the global art market.

In an ongoing global battle against the illicit antiquities trade, Egypt has secured the return of several looted artefacts, including a collection of ancient cartonnage (a plaster-soaked linen material used for mummy masks). These recoveries are linked to a notorious trafficking network allegedly run by the antiquities dealer Serop Simonian. The latest success involved the return of artefacts from Australia and the separate repatriation of ten more items from the United States by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, one of which was proven to have been stolen from an official archaeological storage facility at Saqqara, a major necropolis near Cairo.

This investigation by “Bab Misr” reconstructs the smuggling journey of one specific artefact—a stolen limestone relief—based on official legal documents, revealing the sophisticated and shadowy methods used by such networks.

The Australian Recovery: A Trail Leading Back to the U.S.

Egypt recently received 17 Egyptian antiquities from Australia, voluntarily returned by a private citizen in Melbourne following diplomatic coordination. The pieces had been purchased through online auctions after being shipped from the United States, according to the Art Crime Archive blog. Australian MP Tony Burke noted that some items were identified during Operation ATHENA, a major 2019 global crackdown on cultural property trafficking led by INTERPOL and the World Customs Organisation.

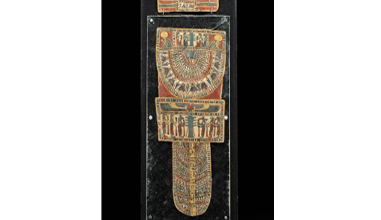

The recovered artifacts included a Ptolemaic-era (332-30 BCE) wooden statue of the goddess Isis, gilded to signify its likely placement in a royal court; funerary items like a Ptah amulet and a headrest amulet, meant to aid the deceased in the afterlife; a coffin panel depicting the sky goddess Nut; a collection of pottery and jars dating from the Predynastic Naqada II period (c. 3500 BCE) to the Ptolemaic era; and a child’s cartonnage set, a decorated plaster-and-linen casing for a mummy.

The recovery was executed under Australia’s Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986, which permits the seizure and return of cultural property that has been illegally exported from its country of origin.

The path of one artefact, the child’s cartonnage set, illustrates the network’s methods. It was listed for online auction in 2020 by Artemis Fine Arts in Colorado on behalf of sellers Theresa and Bob Dodge, with an estimate of $18,000-$25,000. It sold for $10,000.

The Murky Provenance

The auction house listed its provenance as a private collection in Oregon, previously part of “Nile Antiquities” in Kentucky. Crucially, documentation showed it was an earlier part of Serop Simonian’s private collection in Switzerland, having allegedly been acquired from Egypt and transferred to Switzerland in 1972.

A Masterpiece of Funerary Art

The cartonnage set, dated to the 1st century AD (Roman Egypt), is a high-quality piece. Its detailed painting, featuring a white face, elaborate jewellery, gods, and hieroglyphs, suggests it was made for a child from an elite family. The set highlights ancient Egyptian beliefs in bodily preservation for the afterlife, with cartonnage being a lighter, moulded alternative to wooden coffins.

The “Deep Simonian” Network and Its Global Reach

The name “Deep Simonian” refers to the alleged trafficking network of brothers Serop and Hayk Simonian, often linked to middleman Roben Digh. This case is connected to a larger scandal involving the golden coffin of Nedjemankh, looted after the Arab Spring and sold to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2017, which was seized and returned in 2019. In May 2024, the Manhattan D.A.’s office returned 10 Egyptian artefacts worth ~$1.4 million to Egypt, citing the “Deep Simonian” network in eight of those cases.

Places of Theft: From a Village Tomb to a Saqqara Storeroom

Investigations have traced stolen items to specific locations in Egypt. The first is Naj’ al-Hisabah, Qena, where a wooden coffin face was stolen from this village tomb near the Temple of Horus. It surfaced with the Simonian family in 2001, was offered at Christie’s New York, and later traded among U.S. dealers for two decades before being seized in 2023. The second is a Saqqara Storeroom, from which a royal alabaster vase (c. 3100-2670 BCE) was stolen. Discovered by British Egyptologist Cecil M. Firth in the 1920s, it was inventoried and stored at Saqqara. It was later stolen from this official storage, trafficked through convicted British dealer Robin Symes, and eventually seized from a New York gallery in 2023.

Inside a Smuggling Operation: The Case of the “Pa-di-sena” Stele

Official documents from the Manhattan District Attorney’s office reveal the detailed inner workings of the smuggling network, as seen in the investigation of the “Pa-di-sena” stele—a carved funerary slab. The evidence shows a methodical laundering process, beginning in 2012–2013 when emails and photographs circulated among dealers Roben Digh, Serop Simonian, and Christoph Konig. Images depicted the stele soiled and lying on the ground, wrapped in newspaper, indicating it had likely been recently and illicitly excavated.

To facilitate transport, smugglers deliberately damaged the artefact; the stele bore what investigators described as a “clean, single break,” a known technique used to split larger items for easier smuggling. Once removed from Egypt, the next phase involved fabricating a credible history for the piece. For its 2016 auction in Paris, Konig submitted a forged 1977 Egyptian export license and a provenance letter attributed to Simon Simonian. Forensic examination later determined that these documents were produced on the same typewriter, using identical templates as those forged for the infamous Nedjemankh golden coffin.

Finally, the artefact entered a “cleaning and laundering” stage. Digh coordinated the stele’s restoration, after which it was assigned a fictitious collection history—purportedly from the “Old Habib Tawadros collection, acquired in 1970.” Thus sanitised, it entered the legitimate art market and was even shipped to New York for display at the prestigious TEFAF art fair in 2019, before ultimately being intercepted by authorities.

Significance of the Recoveries: Beyond the Symbolic Victory

The repatriation of these artefacts represents far more than a ceremonial homecoming. According to analysis from the Art Crime Blog (Arca), each successful recovery serves three critical, tangible functions in the global fight against cultural racketeering.

First, every intercepted artefact exposes the smuggling supply chain. By tracing an object’s journey from illicit excavation in Egypt, through middlemen and restorers, to listings in auction houses and private collections, authorities can map the transnational networks that sustain this black market. This intelligence is invaluable for dismantling operations piece by piece.

Second, these high-profile returns act as a powerful deterrent against future crime. They send a clear message to the shadowy antiquities market: law enforcement agencies worldwide are actively collaborating, forensic tools are advancing, and the risk of purchasing looted cultural property is rising. The seizure of artefacts, even years after their theft, demonstrates that the paper trails can and will be unpicked.

Ultimately, the most profound impact is the restoration of cultural heritage. Each recovered vase, statue, or coffin fragment is a reclaimed chapter of national history and identity. Returned to its rightful context, it can be conserved, studied by scholars, and displayed for the public, reconnecting a people with a tangible piece of their past.

The meticulous, cross-border collaboration between Egyptian authorities, international law enforcement, and academic researchers continues to methodically peel back the layers of these sophisticated smuggling rings. Their ongoing work is a sustained campaign to recover a nation’s scattered patrimony, one artefact at a time.