The Story of Singing and Arabism with Time

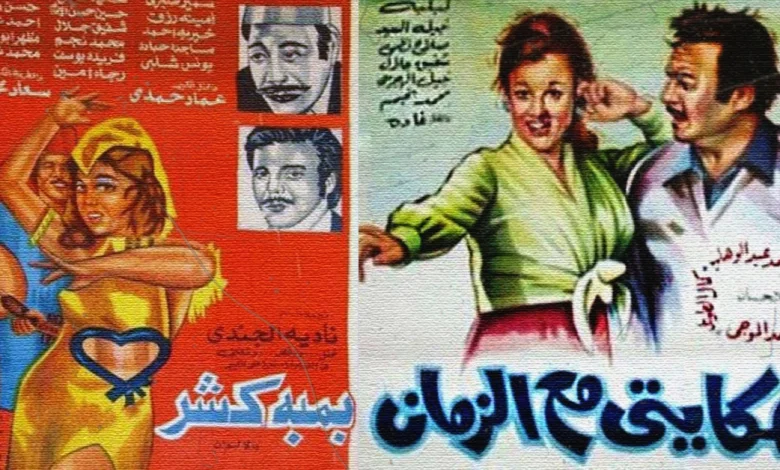

What is the connection between the film “My Story with Time” (1974) starring Warda, and the film “Bamba Kashar” (1974) starring Nadia Al-Jundi?

Hassan Imam directed both films in the mid-1970s, after the October 1973 war. In both films, Hassan Imam presented a heroine who aspires to be a showgirl. This was the case with Nadia El-Gendy in “Bamba Kashar” and Warda in “My Story with Time.”

In the mid-1970s film market, both were stars, one in cinema and the other in singing. However, neither star had yet established herself as a leading lady on screen, nor as a film star, without reservation. Nadia Al-Najdi performed one or two dance numbers in the 1966 film “Too Young for Love,” but she did not become a “star of the masses” until she starred in “Al-Batiniya” in 1980. As for Warda, she never achieved overwhelming success on the silver screen, although she did enjoy great success in her few television series.

Perhaps there is room for another comparison between the two films and their place in the context of Hassan Imam’s continued success in directing sad films belonging to the artistic melodrama genre. Below, I reflect on My Story with Time from angles that critics are not accustomed to viewing Imam’s films from, such as his film’s engagement with the visual traditions of the 1970s, or Hassan Imam’s view of cultural Arabism.

The aesthetics of 1970s cinema

My Story with Time is the story of the lead singer of a musical troupe, played by Warda. She marries a wealthy contractor played by Rushdi Abaza and lives a peaceful, stable life, during which she gives birth to a daughter. However, she disagrees with her husband because of his fondness for staying out late and drinking with bad friends, who also encourage him to bribe public officials in order to obtain lucrative contracts. Warda separates from Rushdi, especially since she misses the arts, so she returns to the troupe and falls in love with its director, an ambitious and innovative artist, played by Samir Sabri. The mother loses her daughter, suffers abuse from the father, and is torn between her love for the arts and Samir Sabri, and her longing for her daughter.

In terms of its story, My Story with Time is closer to the world of films, themes, and issues of the 1960s, even though it was produced in 1974. Visually, however, My Story with Time is quintessentially a film of the 1970s. The story of a mother who disagrees with her husband because of his indulgence in alcohol, staying out late, and fooling around with women, or his involvement in corruption and bribing government officials to facilitate his own business, is a recurring theme with various variations in films from the late 1960s, narrative threads steeped in the atmosphere of the 1960s, when the state dominated all economic activities.

***

These themes and motifs continued to appear in the 1970s as part of the melodrama tradition, which had begun to decline in the 1970s. However, in the 1970s, the focus in the realm of ethics was on corruption within the public sector itself, rather than, as in the 1960s, on the average employer who employs corrupt managers. For this reason, the story of the film My Story with Time bears strong characteristics of the 1960s.

What anchors the film in the visual world of the 1970s are the extremely close-up shots of the lovers Samir Sabri and Warda, which recur throughout the film to the point of excess. Such shots were rare in Egyptian cinema in the 1960s, except in films with a high artistic sensibility, such as Youssef Chahine’s Al-Nasir Salah al-Din (1963). (1963). But by the 1970s, popular directors were increasingly using this type of shot to heighten the emotion evoked by the scene. In My Story with Time, the dance movements and choreography of the dance steps and performances are also distinctly 1970s. The visual imprint of the 1970s is also evident in the film through the noise of colors in the parade scenes, to the extent that one of the parades was dominated by bright green, yellow, and orange colors.

***

In general, the performances in the film were a manifestation of visual kitsch that condensed decades of visual references into a few minutes on screen, in a single performance. In that scene, several dancers appear, evoking the folk dance heritage of the 1920s with their movements, but wearing dance costumes in colors and designs that are distinctly 1970s, such as pure red and blue.

We also see Lubba wearing an Afro wig reminiscent of 1970s music and African-American culture at the time, but she dances a style that combines the hysterical Western dance of the 1950s and 1960s, closer to twist and jerk dances, with hip and buttock movements inspired by folk dance.

Arabism and subjectivity

The film My Story with Time marks a return to the discourse of cultural Arabism, which flourished in the cinema of the 1940s and 1950s and was embodied at the time in a kind of revue consisting of segments each celebrating a particular Arab country and concluding with praise for Arab cultural harmony from the ocean to the Gulf, before the emergence of the phrase “From the Ocean to the Gulf.” In the 1940s, there was a celebration of Arabic song and its unification of Arabic speakers in the East and West, as everyone who used that language listened to it and enjoyed it.

In “My Story with Time,” however, the elements of cultural Arabism are more closely linked to the fabric of the film and its deeper substance. The film is Egyptian, produced by the iconic Egyptian company Sawt al-Fann, and the heroine is Algerian. The film’s credits were careful to identify her by her official stage name at the time: “Warda al-Jaza’iriya,” a name that gradually became simply “Warda” starting in the mid-1970s. The musical troupe in which the heroine sings is called “Al-Furqa Al-Ghina’iya Al-Arabiya” (The Arab Singing Troupe).

This is evident in a close-up shot in which the troupe’s banner occupies the entire screen, the first shot in the film after the opening credits. The singing troupe performs in Cairo and Beirut, as is evident from the sequence of events. The film presents an image of song as a cultural and entertainment link between Egypt, Lebanon, and Algeria.

***

However, the Arabism referred to in the film is not the cultural Arabism that prevailed in the 1960s, which explicitly or implicitly referred to political Arabism and the idea of national unity among Arabic-speaking countries. In the 1960s, references to cultural Arabism interacted with a historical context in which Arab nationalism represented a liberating discourse against colonialism, and thus cultural and political Arabism were intertwined in a sense.

Cultural Arabism in the 1970s after the October 1973 war, as presented by Egyptian cinema, and specifically as presented in the film My Story with Time, is Arabism and an expression of love, pleasure, and desires that the individual self seeks to achieve, in the realm of art and personal life, not in the realm of politics and the public sphere. The film focuses on individual desires, Warda’s desire for love directed at Rushdi Abaza, Samir Sabri, or her daughter.

In the film, the character played by Warda herself sings, expressing the feelings, emotions, and pains of that self. She tells her personal story, as the film’s title suggests, and she tells and sings in an epic way, because she organizes the story of the self in the face of time, or fate, and not just in the face of a limited human life in a specific time.

***

Warda sings and chants, as if she were “speaking” in one of the styles for which Abdel Halim Hafez was famous and in which he excelled, especially in the song that gives the entire film its title: My Story with Time. This may be because the song was composed by Baligh Hamdi, one of the composers closely associated with Halim and one of those who helped shape his singing style.

The film does not present a version of Warda’s story as an artist and a human being, as if it were telling her personal story. Anyone who follows Warda’s autobiography knows that with a little interpretation and imagination, it is possible to draw parallels between the broad outlines of Warda’s character in My Story with Time and Warda’s real life. If we believe the sensational and romantic press reports, we notice that Warda—according to that report—impressed Baligh from the moment they met, just as the character of Samir Sabri, the director (not the composer), fell in love with the character of Warda, the singer, in the film.

***

Warda married a man who belonged to the Algerian state apparatus, just as the character Warda married the character Rushdi Abaza in the film. Then, after ten years of marriage, Warda left her husband to return to art, specifically to several years of intense collaboration with, and marriage to, Baligh Hamdi. In the film, Warda’s character experienced moments of love and artistic collaboration with Samir Sabri’s character after she decided to divorce her husband, Rushdi Abaza’s character, as if that moment echoed Warda’s real-life marriage to Baligh.

The autobiographical aspect intended in this article is not the parallel between Warda’s real life and the imagined life of the character she plays in the film. What is meant here is the film’s production of the idea of a painfully self-centered character, detailing her pain by telling her sad story full of emotional turmoil and grief. It is these highly emotional and self-centered traits that make Warda’s character in the film equivalent to the ever-suffering Abdel Halim Hafez, who is always distraught on screen and portrayed in the press and art history as an orphan and a poor man who succeeded in achieving stardom through his talent.

***

In moments of heightened nationalism, lyricism flourishes in society, as do popular discourses and striking works of art. Egypt, especially in the Nasserist 1960s, experienced this heightened emotionality, one manifestation of which was Halim’s own lyricism: the sad, dreamy romantic or the joy of his love for his girlfriend, who is also the highest model of Arab nationalist lyricism with his voice when he sings national songs on the anniversaries of the July Revolution. Hassan Imam’s film My Story with Time stands out here because it continues to produce highly lyrical, romantically anguished works, but when embodied in Warda in the 1970s after the October 1973 war, they are subjective and emotional, disconnected from any political or nationalist propaganda.

The Disqualified Mother

In the 1970s, Hassan Imam directed a series of films called “The Worlds,” which repeatedly featured the theme of a mother who is deprived of her son or daughter by society because she works as a scientist or a dancer and singer. The truth is that this theme, which is common in classic Egyptian cinema, especially in artistic melodramas, extends in Hassan Imam’s work to stories of women who work in the arts, even if they are not scientists. but they are united by society’s violence against them, which allows the husband, his family, or the court to deprive the child of his or her mother. To some extent, the film My Story with Time belongs to this series, even though Warda’s character is a respected modern singer, not a scientist.

In the film, Warda refrains from demanding custody of her daughter while demanding a divorce from her husband. Warda’s position is based on her preoccupation with art and the singing group, but also because she knows that the judge will not rule in her favor regarding custody because she is an artist. Youssef Wahbi confirms this analysis in his dialogue with Warda. In My Story, Youssef Wahbi plays the role of the orchestra conductor, artistic mentor, and spiritual father to the girls in the singing group, and his approval carries great symbolic weight.

***

In contrast, Rushdi Abaza insists in more than one scene, shouting and ranting, that he will deprive Warda of her daughter. However, the film ends with a hint that the family will be reunited and that Warda will sacrifice her love in order to raise her daughter under the care of her husband, as the closing song ends with shots of Warda leaving the stage accompanied by her husband and daughter.

Perhaps this optimism distinguishes My Story with Time from the rest of Hassan Imam’s films about women deprived of their sons and daughters. But in general, the torment of a mother and her separation from her children is a long-standing melodramatic motif that has often appeared in this genre over the decades. However, it takes on special significance in 1970s Egyptian cinema because it seems to have a contradictory effect. On the one hand, the motif seems to be an incentive to deepen modernity and to reject the judicial system and social structure’s bias toward men at the expense of women.

***

On the other hand, the proliferation of this motif in the 1970s led to an increased sense among people that the suffering experienced by women in their conflicts with their husbands was caused by the women’s rebellion, and thus people tended to hold women responsible for the conflict with their husbands/fathers. There may seem to be some confusion in analyzing the impact of this dramatic motif. The mother’s relationship with her children may be complicated by the father’s revenge against her, and this situation may provoke people to restrict men’s privileges in personal status courts. However, on the contrary, the mother’s pain may have led people to adopt a conservative stance, assuming that a mother who resists masculinity and authoritarianism brings trouble upon herself and her family. This ambiguity is what makes Hassan Imam’s films relevant in more than one historical context.