The story of Safaga: phosphate mines and the sound of history passing through generations

At first glance, when you enter Safaga, you might think it is a modern city that cannot be compared to the ancient Egyptian cities with roots deep in history. But once you delve deeper into the neighborhoods of “Safaga al-Balad,” this charming city reveals its secrets and endless stories, overlooking you with its ancient landmarks that bear witness to the dreams, ambitions, and hopes of successive generations.

It casts its ancient charm upon you, the same charm that attracted a young English engineer in 1902, who came to sketch different features within the city, features that brought together multiple cultures and social classes. He succeeded in establishing a vibrant life that still resists time and preserves for itself an eternal presence in the consciousness of the place.

Establishment of the company

The historical epic began in Safaga in 1902, when English geological engineer Indy Kraxine discovered phosphate ore in the Red Sea mountains of the city. This sparked the transformation. He founded the Safaga Phosphate Company, and in 1910, the region witnessed the first train loaded with phosphate heading for the port of Safaga, heralding the beginning of a new era that completely changed the face of the city.

Ali Ghazali, an agricultural engineer and heritage enthusiast from Safaga, says: “Indy was keen to establish a company that operated according to strict English standards of discipline and precision in work. He built houses for the workers, dividing them between accommodation for unmarried workers and accommodation for those living with their families. He also established a research laboratory to analyze phosphate ore and appointed an English engineer to run it.”

The company’s buildings are full of memories

Abdulwahab Mubarak Hassan, 70, one of the company’s employees, says: “Safaga Phosphate was founded in 1902. It continued to operate under foreign management until it was nationalized in 1956. It was then merged with Luxor Phosphate Company under the name: Red Sea Phosphate Company – Luxor Sector.” In 2000, it was merged again with Al-Nasr Mining Company, which included the sectors of Safaga, Al-Qusair, Al-Hamrawein, and Al-Saba’iya.

He adds: The company’s original buildings were included in the expansion of the Port of Safaga. The company had about 4,034 employees. Its annual production reached about 300,000 tons of the highest quality phosphate, at a rate of 25,000 tons per month. It was exported to several countries, most notably China, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and North Korea.

Foreign faces shaped the company

Ghazali adds: Indi was keen to construct the company’s buildings in a prime location overlooking the Red Sea and close to the port of Safaga, to facilitate transportation and export operations. In addition to the company’s buildings and facilities, he established a private club for workers and another for employees. He also established a clear career progression system to ensure worker loyalty and discipline.

He pointed out that the company’s organizational structure bore the clear imprint of its founder’s thinking, who assigned important positions to foreign talent. Two Englishmen were put in charge of research, the laboratory, and financial affairs, while an Italian was put in charge of personnel. Among Indy’s most prominent assistants was a man named “Al-Khawaja Balto,” who was so attached to the place that he chose to remain in Egypt even after the company was nationalized. He was buried in the city of Safaga.

Mohamed Mubarak, former secretary of Safaga and one of its sons, shares Engineer Ghazali’s opinion. He affirms that this giant mining fortress built by the British in Safaga was completed with Egyptian hands, both in the field of geology and among the miners. Despite the harsh working conditions at the beginning, where the company’s founders refused to allow workers to have families and tightened control over them to the point of monitoring them with binoculars from the highest peak in the area, the work continued and the company remained.

The life of phosphate workers

Engineer Ghazali continues, saying, “The company attracted workers from all over, and everyone had to comply with the rules and regulations. While the management was keen to provide a decent life for the workers, it built them high-end housing.”

The company also established the first telephone exchange and the first post office near the beach in Safaga. Both are still in operation today, preserving the memories, secrets, and stories of the employees and workers who made the company’s history.

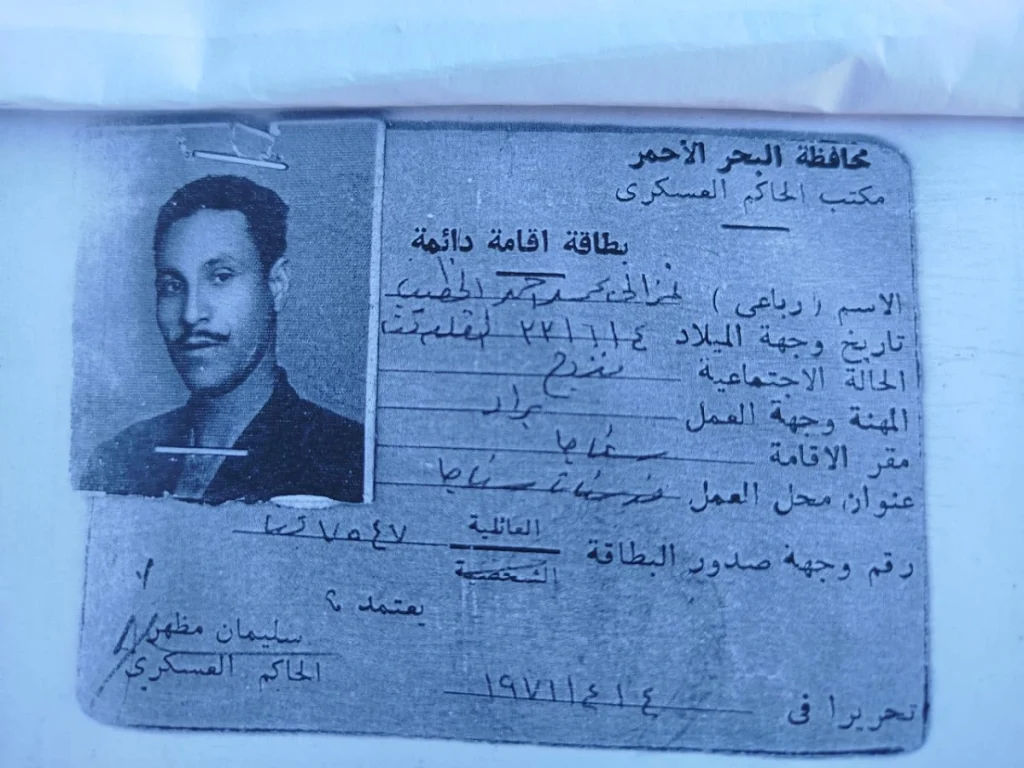

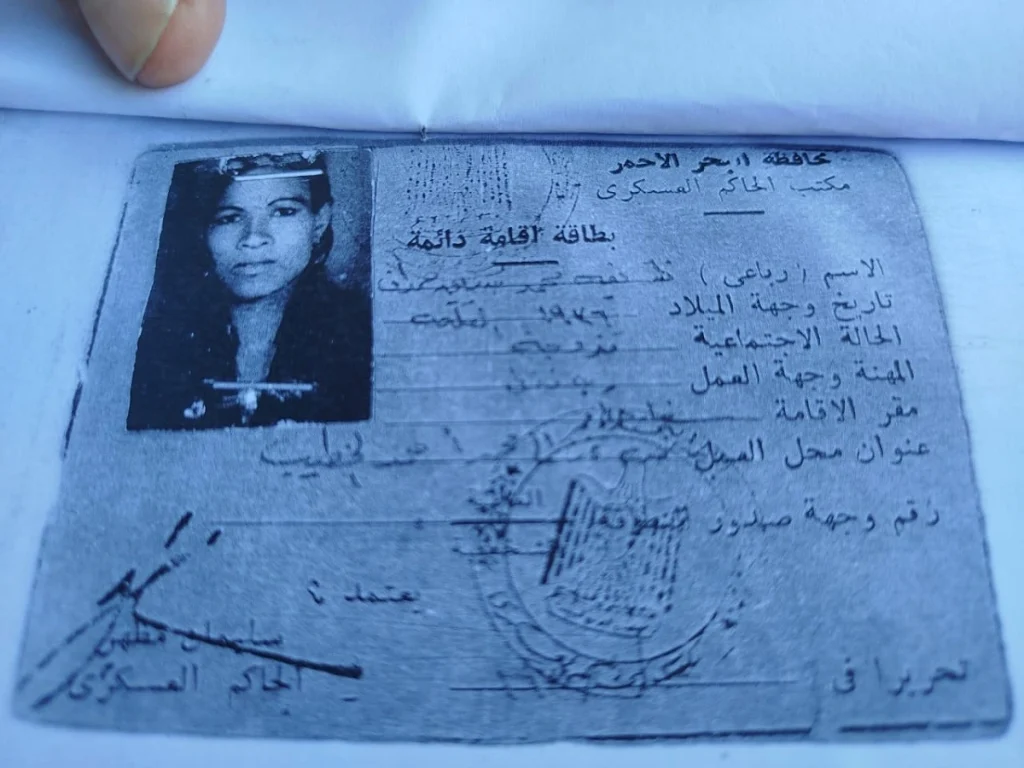

Permission to enter Safaga: between suffering and self-sufficiency

With a voice full of nostalgia and sorrow, Ghazali recounts the suffering endured by the workers before they were allowed to bring their families. He says: “Even after the permit was issued, entering the city of Safaga remained extremely difficult, as it is a border area. It was necessary to obtain permits from the border guards that included accurate information about family members, down to the color of their eyes and their height. To ease the burden of these restrictions, the company set up a flour warehouse and a bakery that distributed five loaves of bread per day to each worker. In addition, families who preferred to bake bread at home received a monthly bag of flour.”

Ghazali recalls those days, saying he still remembers the sight of flour and bread being distributed. He recalls how the company was keen to provide self-sufficiency for its workers, preserving their human dignity and strengthening their desire to continue working. The bakery and flour distribution outlet are still in operation today, as if they were witnesses to a period that shaped the city’s history.

The quality of Egyptian phosphate… The secret of global excellence

The secret behind choosing Safaga as the English mining stronghold was the unique characteristics of Egyptian phosphate ore. It turned out that its chemical composition and high temperature gave it a qualitative advantage over its counterparts in other Arab countries. This made it an ideal material for use in many vital industries.

This prompted the company to intensify its efforts to search for more mines, bringing the total number to ten. The most famous of these are: Abu Rabah, Abu Youssef al-Janoubi, Namra Khamsa, Namra Sab’a, Abu Adlan, al-Baydani, al-Suhaymat, the Koberi al-Haw mine, the Abu Adla mine, and the al-Jassous mine. Thus, Safaga became a unique center for the phosphate industry and a name that is often mentioned in global mining records.

A break on the plateau… Mr. Indy’s legacy remains in Safaga

Adel Abdelghani, 65, who was a division head at the company, describes the company founder’s rest house as being located on top of a high plateau in the Safaga Leda area. It was built in a location from which he and his assistants at the time could follow the details of the work and the movement of life in the emerging city.

The rest house was built in the traditional English style. It was a single-story building surrounded by a wall of huge stones. The walls of the rooms were built of mountain stone to blend in with the natural surroundings, and behind it stood a suspended water tank.

This is where the company’s founder lived. And this is also where the story continues, as it was later converted into a rest house belonging to Al-Nasr Mining Company, remaining an architectural witness that tells chapters of the city’s history and the phosphate industry in its surroundings.

The VIP Rest House: A Window to the Sea from the Heart of the Mountains

Abdel Ghani adds that the VIP Rest House was built on the highest flat point of the Safaga Mountains, as an architectural masterpiece that combines simplicity and luxury, and the hardness of stone with the warmth of wood. Stone was chosen to build its walls, giving it durability and timeless beauty. The steeply sloping roofs are supported by finely crafted panels, topped with prominent chimneys that lend the place a special aura.

The lounge is unique in its design, blending English country style with an Eastern ambiance, decorated with wood used in both the furniture and architectural details. Some of its walls are adorned with decorative wooden or half-wooden panels, adding warmth and intimacy.

The windows and balconies, both open and closed, were cleverly designed to overlook the Red Sea, giving visitors the impression that they are sitting on the water’s surface rather than on top of a mountain, in a beautiful harmony between architecture and nature.

A place for stories… Memories of leaders and innovators

Due to its unique location and design, the VIP lounge became a destination for prominent figures in Egyptian society at the time, including politicians, artists, and intellectuals. The people of Safaga say that its walls have preserved the echoes of historical stories. It hosted Egypt’s first president, Mohamed Naguib, Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, and Yugoslav President Josip Tito.

It was also visited by a number of governors and ministers, including Lieutenant General Saad El-Din El-Shazly, as well as an elite group of writers and intellectuals who found in it a refuge that combined the tranquility of nature, the charm of the sea, and the fragrance of history.

The first school in Safaga: childhood memories and a factory for leaders

With a story filled with nostalgia for his childhood days, engineer Ali Ghazali led us to the second school established in Safaga after the English school. It was built in the 1940s next to the Grand Mosque in Safaga. There, the classrooms were filled with the voices of young students under the care of teachers who were distinguished by their dignity and prestige. Among them were Al-Desouki Afandi from Mit Ghamr, Mahmoud Afandi from Damanhour, and another from Qena. They wore traditional Egyptian clothing consisting of a jubbah and caftan. The school produced many leaders, many of whom were from the village of Um al-Huwaitat, who later carried the banner of leadership and thought in the city.

Ghazali recounts that the phosphate company did not stop at serving its workers. It also provided one of its shift buses for use in the morning to transport school students. This gesture embodied the solidarity between the company and civil society.

The first elementary school was located a few steps from the Red Sea coast. It was built in a circular design, starting with first grade classrooms and ending with sixth grade classrooms, in a circle that closed around the principal’s office. All classrooms overlooked the sea. It was a beautiful scene, suggesting that the sea itself was a witness to the dreams of the children, who later became the city’s leaders and prominent families.

Company clubs: a mirror of class society

Ahmed al-Sisi, a native of Safaga, recounts that the company did not neglect the recreational needs of its workers, establishing clubs near the beach in Hajar as a place of respite for them and their families.

These clubs were a vivid reflection of English society in 1910. There was a clear separation between the workers’ club and the employees’ club, and the children of workers were not allowed to enter the employees’ club.

With this separation, the company established strict class traditions. The workers, the laboring class, struggled to meet their basic needs and worked in manual or semi-manual jobs. Senior employees, on the other hand, enjoyed extensive privileges: a good education, prestigious social status, and economic security. They enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle surrounded by luxury and services.

Thus, the company’s clubs became a mirror reflecting the class distinction between two groups under the umbrella of a single institution. This scene sums up many of the characteristics of industrial society at that time.