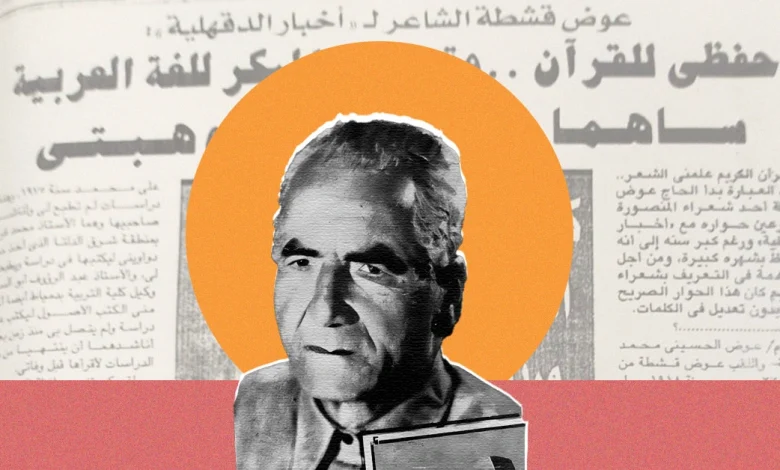

From groceries to poetry: The story of Awad Qishta, the forgotten poet of Dakahlia

“To you, shining from your tower in the distance, giving and not taking, like all great ones… O poet of Egypt, buried in a world of falsehood, beneath the rubble of oppression… I salute you as you struggle to live, forgetting the bitterness of life in moments of creativity. And to you there… where you live in the shadows, shining the spotlight on others.

Awad! O poet of Egypt!

One day, literary history in Egypt will awaken and regret every moment it did not appreciate you. Your poems, your verses, and your approach to life will become a playground for scholars and seekers of literary pleasure. You will die, yes, but the poet Awad will not die. You will remain in the conscience of this nation as a piece of its joy, its feelings, and its great pain.

Until we meet, and we may not meet, I salute you.

Salah Hafez.