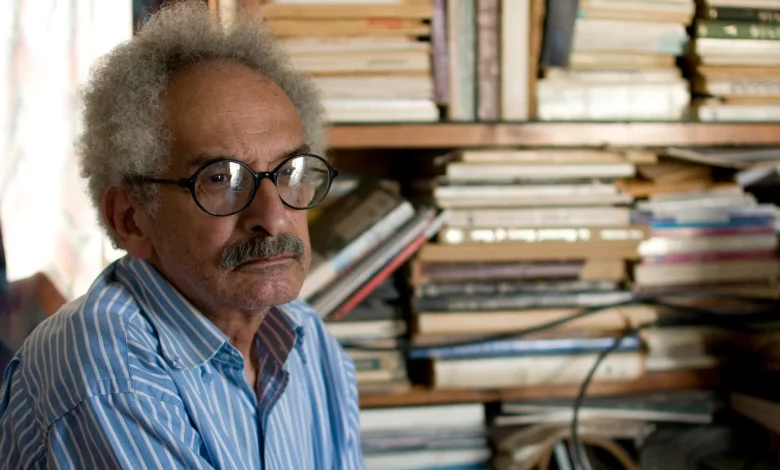

Profile | Sonallah Ibrahim: My Experience as a Novelist

I have tried my best to avoid talking about this subject, for the simple reason that I believe that two or three novels do not make a writer, and that one can only talk about the experience of writing novels through the number of works one has produced. However, it was necessary for me to participate in this important forum, and since I had deliberately distanced myself from theoretical and critical activity, I had no choice but to engage in this discussion.

I do not believe that this is the place to discuss the circumstances and factors that led me to write the novel, which is in any case a subject that has been dealt with at length by many great writers around the world, making it difficult for me to add anything of value to what they have already said, despite the particular nature of my experience. Suffice it to say that I decided to write the novel as a means of self-affirmation and self-defense in extremely difficult circumstances, namely prison. Obtaining paper and a pen, both of which were forbidden, and then finding a suitable hiding place for them, represented a victory over the bars, and on the paper I was able to exercise all the freedom I lacked.

***

From the outset, I was fascinated by the game of form. The freedom with which contemporary writers treated the novel as a medium excited me greatly. Every novel becomes a complete surprise and a new adventure, without repetition or banality. It was only natural that my childhood, whose most vivid moments had been awakened during my long days and nights in prison, should become a rich source of material for my first work. But I wrote only a few chapters before I came up against the problems that every writer faces at the beginning of their career, and often after their first novel: which of the dozens of paths to take? Which styles, forms, and schools? Chekhov, Gorky, Joyce, Proust, as well as Zola, Balzac, Naguib Mahfouz, and now Robbe-Grillet and the authors of the nouvelle vague in France, who were causing such a stir at the time (the early 1960s)?

It was not just a matter of craftsmanship or technique, but rather of perspective, vision, and what you want to say. I began my movement in rebellion against what was then known as socialist realism. Like many others, I felt that it falsified and embellished reality, and I believed that this deception did not help people but rather misled them.

So I vowed from the outset to tell the truth, and because the truth is not absolute, I must make every effort, armed with knowledge and experience, with Marx, Freud, and those who added to them, to get as close to it as possible. I had enough arrogance at the time (I was still only 22 years old) to promise myself that I would not repeat or imitate, and that I would remain silent if I had nothing to add.

***

During that time, a huge secret library was assembled in the desert prison where we were held. The library was extremely diverse and contemporary, even including the latest French literary and theoretical studies and journals. I had a rare opportunity to read in a variety of fields. I reread what I had read before with a different eye, searching for answers to specific questions.

I enlisted the help of the late Ibrahim Amer to translate into Arabic, which I do not speak, all the philosophical and literary studies that interested me, including a fascinating study published in La Nouvelle Critique on the architectural structure of the novel Polisse.

I came across two books on Hemingway that had a profound impact on my career: the first by American critic Carlos Baker, and the second by Soviet critic Kashin or Kashkin (if memory serves me right). In my opinion, these two books represent one of the rare cases in which the critic is an aid to the writer. They delved deep into the artistic vision of the great American writer, focusing primarily on his tools and the rules he set for himself. My own temperament accepted many of these rules, finding in them pillars to lean on in the early stages: I should write only about what I know well – prose should be realistic, highly specific, and multi-dimensional (The Iceberg) in contrast to traditional Arab fluidity – focus and reliance on the internal associations and implications of prose, and the omission of anything superfluous, i.e., anything that can be dispensed with.

***

I returned to trying to write. It was difficult to write about the prison experience because I was living it and many aspects of it lacked clarity. It was natural for me to return to the mine of my childhood, so I decided to extract moments that I could control, within the limits of my current consciousness. I still cherish the most tender feelings for those moments when I was alone by the prison wall, overlooking vast expanses of desert sand, writing chapters of a second novel, which was also never completed.

We were suddenly released in mid-1964, a few days before the diversion of the Nile and the completion of the first phase of the High Dam. I was released after five and a half years in prison, to face a different world due to the profound changes I had personally experienced (I entered prison at the age of 21 and left at 26), in addition to the changes that had taken place in society as a result of the social revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser in the early 1960s. I found that some social classes had disappeared and others had emerged. Televisions occupied most homes. People were suffering from very different concerns.

***

And there were things that were incomprehensible: there was talk of socialism being implemented, which was what I had dreamed of and gone to prison for. But those who were implementing it and benefiting from it were various factions of the petty bourgeoisie, who had broken free from their shackles to spread their ideas about life, literature, politics, and art in the name of scientific socialism. It was a different world from the one I had dreamed of. But the regime was embroiled in a fierce battle with imperialism, and there was only one place for a political activist: to stand in the ranks. As for the novelist, what could he do?

It was difficult for me to shut myself off from what was happening around me and bury it in the rich mine of my childhood. All my attempts to finish the second novel I started in prison failed. Instead, I would return to my room every evening to feverishly record the events of the day, without any attempt to analyze anything, limiting myself to the shocks I received every hour during my futile search for work and a woman. and through my attempts to clarify my position on the questions that rained down on me from relatives, acquaintances, and friends.

One day I will never forget, while I was angry with myself for my inability to write, and questions about my own path and my unique voice began to torment me again, I glanced at these feverish lines that had accumulated on a few sheets of paper and found myself in Archimedes’ position. Here was the truth I was looking for. Here was a raw piece of reality, unadorned and untainted by political or philosophical theorizing that might be mistaken. A raw piece waiting for the artist’s fingers to shape it into a complete and distinctive being. I had found my own subject in its distinctive form.

***

While the short sentence with its dry, indifferent surface was, in my previous attempts, a principle borrowed from Hemingway, who raised the slogan “touch and go” at the beginning of his work, here it springs from the work itself: In my feverish attempt to capture his moment in unfavorable circumstances, I did not have the opportunity to delve into the details and investigate the background and explanations. But my “sentence” was born pulsing with hidden currents and nuances that complemented this deficiency and spoke to the reader, both consciously and unconsciously. At times, I found it insufficient, so I completed the situation with an emotional counterpoint. At other times, I found it repetitive and unnecessary, so I deleted it. This is how That Smell was born.

This short novel was met with complete rejection at first, both by the state, which banned it, and by critics who attacked it. Readers who managed to get hold of it were shocked by its harsh frankness, which touched on their ideological and traditional foundations.

In my opinion, this shock is proof of its success and an early sign (in early 1966) of the tragedy of 1967 and the setbacks that followed. It confirmed the protagonist’s alienation from what was happening around him and his rejection of what was conventional, bourgeois, and inhuman. Strangely, a number of prominent progressive critics saw in it “Chewa” and denounced this incomprehensible alienation, attributing it to the inability of intellectuals isolated from social phenomena to understand them. They viewed it from the perspective of accepting the reality of the present in the hope of developing it in the future through a unity devoid of conflict between progressive forces, which is in fact absolute subservience to the revolutionary dictatorship.

***

That Smell defined the position to which my particular disposition impelled me: the unity between the novel, reality, and the author, a unity that always kept me on the edge of autobiography, separated from it only by the barrier of artistic form. Less than three months after finishing my first novel, I was on my way to work at the High Dam. With the restrictions imposed on freedom of action, the High Dam seemed like the only place where this freedom could be realized, not to mention what this structure meant in material terms for the future of my country. I had various doubts and wanted to make up my mind about them. I was looking for a woman: for my sexual identity, which had been greatly confused by conflicting and successive events in my life. I was still finding my way in writing. By chance, I had brought with me a book about Michelangelo, which I read before going to sleep every night, as was my habit, and I found in his artistic career

***

As the author of the book explained, it echoed the artistic problems I was experiencing. He was the one who refused to make his first subject a myth, as his teachers wanted, and insisted that it be something personal to him. He wrote these lines about the role of the artist:

“No idea comes to the artist, however great he may be,

nor does it exist in the crust of rock.

All that the hand that serves the mind can do

is to break the spell of marble.”

This is a complete manual for artistic creation, and even a philosophical vision of life and action in general. I set out to discover the geographical, engineering, historical, political, and human features of the High Dam, and soon I became “me,” the dam, and Michelangelo, an indivisible, interactive unit. In this unity lie the conditions required for the novel: all I have to do is break the spell of the marble.

Geographically and architecturally, the dam consists of three sections: a front section, a rear section, and a third section between them. My journey also consists of three sections: Cairo, the dam itself, and Abu Simbel. The structure consists of the front and rear sections, which are made up of four different processes, each linked to a specific wheel and a specific material.

***

Four seasons ascended to the dam and four descended from it. The dam itself has a heart: the solid core or impenetrable iron curtain, which, strangely enough, is made of the simplest and weakest of materials: earth. But when this earth is mixed with water and injected with certain materials imported from the Soviet Union, it turns into a barrier against time. In this middle section, all the elements of the dam and the novel come together, and those fragments, gestures, memories, and events converge in a living focal point, a moment of tense action, which is conditional salvation (through love) and exile (for what is all this?).

I raised the slogan of achieving maximum unity between form and content. I spent months trying to give every page of my manuscript, every paragraph on that page, a form that corresponded to the main materials that made it up: rocks, sand, and dust. Then I abandoned this goal—in terms of visual form—when I realized it would take me years. I focused my efforts on language.

In that scent, my language was spontaneous, with a certain rawness that I deliberately preserved when I found it had a particular aesthetic quality that served the intended discourse. But Najma Aghth required a different approach to language, given the desired unity between form and content. Rocks, the main material used to build the dam, are, in Michelangelo’s words, something certain that cannot be discussed from any angle. In the process of gathering the scattered fragments of the world for the dam, where everything is open to interpretation and analysis, there was a need for these rocks, the indisputable pillars.

***

The resort to a cold, reportage style, tried before, with a new addition, is to take care to be extremely precise, to make words correspond exactly to their meaning, and to avoid all traditional linguistic and literary devices and tropes. Sand is another important building material. It is sometimes coarse and sometimes fine. Originally, sand was sedimentary rock that was deposited over time and broken down by erosion. Does this material, used in dams, correspond to another material in the novel, namely memories? And the reflections associated with Michelangelo’s artistic creativity? This is where the lyrical style in the emotional contrasts to the main narrative comes from.

In the middle section, where all the elements are mixed together in a living unity, there is an urgent need for a single tense sentence that captures that rare moment, the moment of action on its multiple levels (gender, politics, art) in a brief and profound moment of realization.This is where the stylistic linguistic plurality came from, whose significance Dr. Barrada was the first to highlight in his valuable research, considering it key to defining the worldview in August Star.

***

Previously, Dr. Boutros Hallaq had made a profound effort to study the internal structure of the novel, but he imposed on it preconceived conclusions that agreed with his own views on modernity and contemporaneity. For this reason, he did not bother with this stylistic plurality and stopped at the reportage style of the main narrative to extract from it aspects and even imitations of Michel Butor’s novel Les Passages. In fact, I have not read the novel in question, because I do not read French. As for my readings in English of the works of the authors of the new novel in France, they have not gone beyond a few works by Rob Alan Jarbier, Natalie Sarout, and Claude Simon. The funny thing is that I have only read a few pages of these works, which bored me so much that I have not continued reading them to this day.

But this is not enough to deny the possibility of being influenced by this school through critical studies and press reviews. And I see no harm in this influence, if it is true. We do not write from a vacuum. It is my right to benefit from the knowledge and experiences of others, provided that I add something to them. Literary history is a history of additions and transgressions. I have already admitted that I graduated from the Hemingway school. But influence is not imitation or mimicry. If someone uses internal monologue, does that make them an imitator of Joyce? The problem always lies in the vision.

***

For example, the machine is an enemy to the authors of the new novel in France. In “August Star,” contrary to what Professor Boutros al-Hallaq believed, it is a close friend. Professor Mahmoud Amin al-Alam gave this point its due in the research we heard. But his research was generally closer to a journalistic presentation than to a deep critical analysis.

Professor Al-Alam himself recounted in his opening speech how, in the 1950s, he raised the slogan of contemplating the literary phenomenon in terms of form and content, because form is not the external framework of literary creation but an internal process that is effective within it, and the relationship between the two is organic. The professor acknowledged in his speech that, in practice, he had remained at the level of external phenomena and had not delved into the depths of internal technique. He said that he now aspired to a criticism that would examine “with precision and care the internal technical details of the literary work” as a starting point for determining external meanings.

However, his research fell short of this ambition, as he limited himself to the general external phenomena of the novel, that is, the aspect of criticism directed—through the newspaper—at the reader. So why should I, the writer, benefit from such criticism?

***

The relationship between Arab writers and critics is still an uneasy one. Writers look to critics to crystallize—I won’t say solve—the problems they encounter in their work, and to offer insightful opinions based on a broader, analytical, comparative, and experienced perspective that they can use as a guide. But with the exception of a few cases, Arab critics offer nothing but discourse aimed solely at the reader.

I must therefore focus on my own problems in complete isolation: Do I have the right to write from a perceived unity between my human self, my fictional self, and reality itself? Should I continue on my anti-“authorial” path, which is close to autobiography? If I spice it up with a few tricks, such as the detective genre, could I use it in August Star to create suspense and reach a wider audience? How can I tell a story that will entertain the average reader while also responding to the demands of the educated, discerning reader, without compromising the principles that govern the unique vision I aspire to express? Don’t the strict rules that writers impose on themselves become a prison? Haven’t many beloved works of world literature been written freely? Does a writer ever reach a level of skill and maturity in his work that allows him to break the rules he has set for himself? And doesn’t that mean creating new rules? Can new rules be more flexible?

***

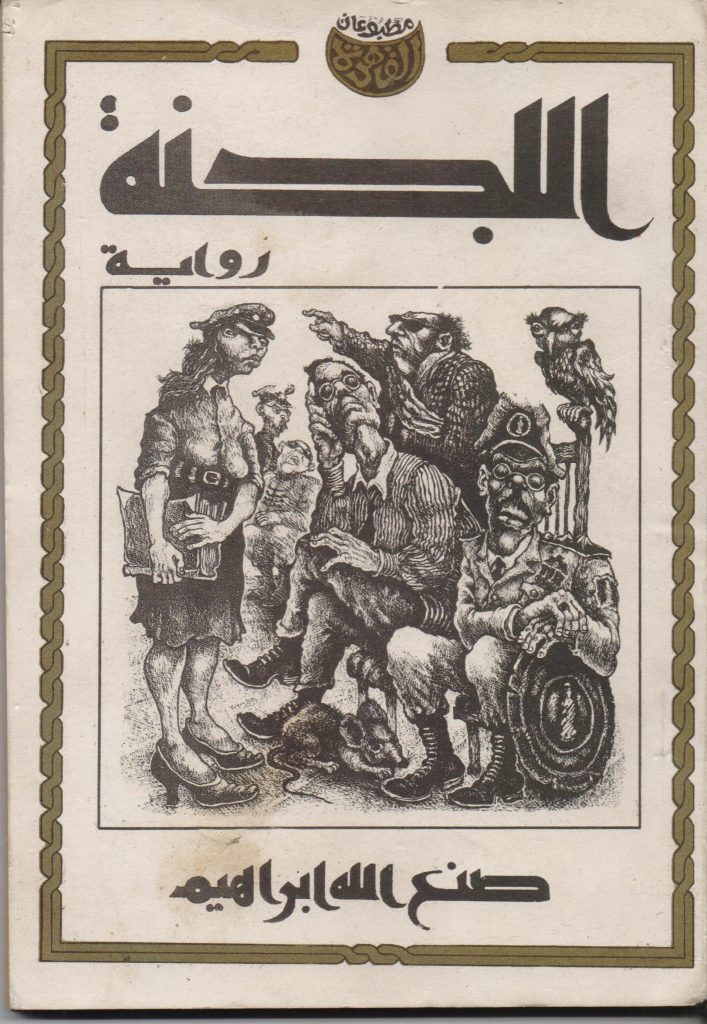

At the beginning of this year, I wrote a short story called “The Committee,” which has now been turned into a novel. I wrote it as an act of rebellion against all the rules that had imprisoned me over the years. It is essentially very spontaneous, though it is governed by its own laws. It is not a piece of reality that the artist reshapes into a new reality; from the outset, it is a completely parallel reality, in the style of the literary tradition. Is it a new “move”? I don’t think so. Before it, I was working on a new novel that represented a development of the principles that governed “August Star… And when I finish ”The Committee,“ I will return to work on the other novel, and ”The Committee” will be nothing more than a whim of rebellion against myself.

It is a game of imagination that may or may not be repeated. It is the same desire that drove me to write scientific novels. It is something different from what is known as scientific fiction. I have written four of them so far, which will soon be published by Dar Al-Fata Al-Arabi (Beirut), following the same approach: a deep study of the scientific material and dealing with it with an open imagination (while maintaining scientific accuracy) in order to give it the necessary form and style. Each novel becomes an independent adventure. In scientific novels, there is no room for neutral or concise sentences. “Iceberg” is of no use here. The details of this world must be explained so that the reader can understand it. It is fine to use similes and all kinds of linguistic devices to achieve this goal.

***

There is a “rock” to rely on: everything is subject to what you want to say. It is a very old saying that proves its relevance every day.

But it is not that simple. There must be maximum freedom of imagination, maximum knowledge of the facts of life, science, the laws of society and evolution, world heritage and contemporary experiences, maximum daring to experiment, break old rules and create new ones, and, above all, honesty.

Read also: