The timeless journey of Carmen: excerpts from ballet, musical theater, and contemporary opera (3-4)

Manifestations of emotion and destiny in ballet and musical theater

Far from the opera stage, where Carmen first achieved fame, her story has inspired countless artistic adaptations in other performances and genres, most notably ballet and musical theater. These adaptations, which transformed the primary medium of interaction from sung text to other forms, rely on choreography, different musical styles, and distinctive theatrical traditions to reinterpret the narrative and its characters.

Looking at these works through the “Theory of Adaptation,” taking into account the concept of “re-encoding across media” and the “palimpsestuous” nature of audience reception (where memories of the opera or other versions influence the experience), reveals the diverse ways in which the creators of the performances have embodied Carmen’s passion, sensuality, and fate on stage.

With its multiple treatments, Carmen is not just a timeless story, but an ideal case study demonstrating the vitality of the theory of appropriation itself. The abundance and diversity of these adaptations make Carmen a fertile field for testing concepts such as recoding and cumulative reception, where appropriation is not seen as a secondary or derivative process, but as a creative process in its own right. Thus, we are not merely presenting a historical account of Carmen adaptations, but drawing attention to the importance of the theory of appropriation as an essential critical tool in contemporary cultural studies.

Manifestations of ballet: dance of passion and destiny

Many famous and influential choreographers have tackled the story of Carmen, translating its dramatic intensity into the language of dance and relying on the expressive potential of the body to convey complex emotions and relationships.

Roland Petit’s ballet Carmen (1949): Revolutionary sensuality and theatricality:

Roland Petit‘s ballet Carmen, produced in 1949 for his company Les Ballets de Paris, was a groundbreaking production that had a profound influence on 20th-century ballet. This work was born out of a rebellious modernist movement, with Petit (1924-2011) founding his own company in 1948 after leaving the Paris Opera Ballet in search of a more daring and innovative artistic horizon. This concentration of creative power in his own hands – as choreographer, principal dancer and founder of a company – allowed him to present a visionary work that combined dance, performance and visual design in a coherent and powerful way, explaining its resounding success and lasting influence.

Betty himself played the role of Don José, while Zizi Jeanmaire gave an iconic performance as Carmen that launched her career. The script drew its inspiration more from Mérimée’s novel than from Bizet’s opera, although it used Bizet’s music in a new orchestration by Tommy Desserre. . The choreography was revolutionary for its time, blending classical ballet technique with Spanish dance expressions, mime, and a bold modern sensuality.

The ballet consists of five scenes and features designs by the prominent Catalan artist Antoni Clavé, who brought his distinctive visual vision to the work. The show was notable for the appearance of Janmer with a pixie haircut and unconventional costumes, marking a clear break with prevailing classical aesthetics. Betty’s London premiere was hailed as an “unparalleled and magnificent” success, widely praised for its expressive, sensual and dramatically intense dance language. Betty’s Carmen became hugely popular, performed thousands of times worldwide, and remains a cornerstone of the ballet repertoire, establishing a powerful choreographic interpretation focused on primal emotion and spectacular theatricality.

Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite (1967): Alberto Alonso’s Carmen Suite The Soviet-Cuban challenge and destiny:

The Carmen Suite, choreographed by Cuban Alberto Alonso in 1967, offered a distinctive Soviet-Cuban perspective. This work was not merely an artistic event, but a geopolitical one, bringing together a choreographer from a Soviet ally and the most prominent stars of Soviet ballet. Alonso was commissioned to create this one-act ballet especially for the legendary Bolshoi Ballet prima ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, who held the title of Prima ballerina assoluta and was considered a cultural icon of the Soviet Union.

The ballet was set to a modern, percussion-rich arrangement of Bizet’s music by Plisetskaya’s husband, composer Rodion Shchedrin. The work focused intensely on the central emotional triangle and the inescapable force of fate, which was often embodied as a character on stage. Alonzo’s choreography combined the rigor of classical ballet with the fiery energy of Spanish and Latin American dance forms, reflecting his Cuban origins and creating a work of great style and explosive emotional charge.

***

The minimalist set design by Boris Messerer featured a symbolic bullring. The ballet emphasized Carmen’s independence, fierceness, sensuality, and defiance of patriarchal control.

The ballet’s overt sensuality and modern music caused a huge controversy in the Soviet Union, leading to an initial ban by the authorities, who deemed it “disrespectful to Bizet” and “morally suspect.”

This cultural-political clash highlighted the tension between artistic expression and government censorship. Despite this, Balanchine fought for this ballet, which became a hallmark of her career and achieved worldwide fame. Her determination to perform it represents a victory of artistic individuality over the collective ideology of the state, making her a great dancer and an “artistic activist” during the Cold War. Carmen Suite is celebrated for its innovative music, dynamic choreography, and powerful portrayal of Carmen as a symbol of freedom and tragic destiny.

Mats Ek’s Carmen (1992): Psychoanalysis and the Deconstruction of Gender Roles:

Swedish choreographer Mats Ek, known for his insightful psychological reinterpretations of classical ballets, created his version of Carmen in 1992 for the Cullberg Ballet. Unlike Béjart, who focused on sensual drama, and Alonso, who focused on fate and symbolic destiny, Ek strips Carmen of its dominant mythical character and places it in a mundane, sometimes “vulgar” context. This shift from the universal to the particular, from the symbolic to the psychological, is characteristic of his postmodern approach, in which he does not retell the story but analyzes the psychological motivations of its characters.

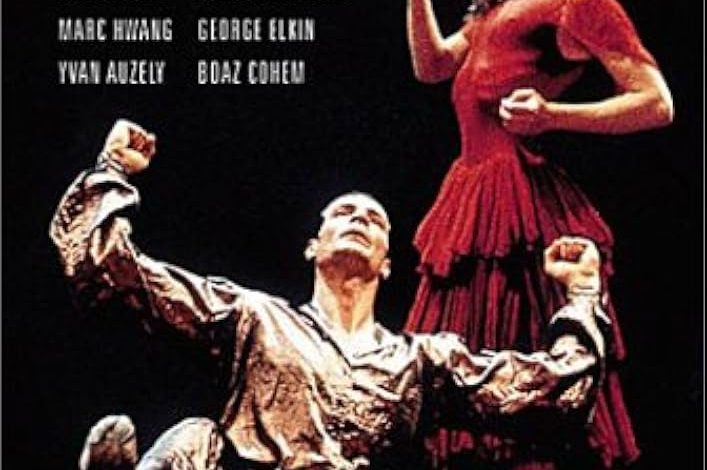

Using the music of Bizet/Chedrin, Eik delves into the inner lives of the characters and subverts traditional gender roles, drawing inspiration from Mérimée’s novel. Carmen, originally played by his wife and muse Ana Laguna, is portrayed in Eik’s version as an independent working woman, while Don José (played by Marc Hwang) is presented as a man longing for domestic life and stability. Escamillo remains the attractive rival.

***

Eck uses his distinctive contemporary dance style—grounded, quirky, introverted, and often incorporating humor and everyday gestures—to explore the psychological complexities of relationships.

This movement style expresses ideas and feelings in a direct, physical way, which can be described as “kinesthetic” expression. The choreography focuses on expressing inner turmoil and questioning social norms.

Like his other works, in which he reworked classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake, Eke’s interpretation is seen as both provocative and insightful, offering a feminist and psychoanalytical reading of the myth that resonates with contemporary sensibilities. Although he has sometimes been accused of disrespecting the source material, his version of Carmen is widely performed and recognized for its ability to make the classic story relevant through a modern and unique perspective. Eak’s work represents a “humanization” of the Carmen myth, in which larger forces (such as fate or mythical passion) are transformed into internal psychological conflicts and contemporary social dynamics.

Musical theater: Americanization and race politics

Carmen Jones (Stage Musical), (1943): Cultural crossover and representation issues:

Broadway embraced this show, written and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II to music by Bizet, with orchestration by Robert Russell Bennett. It was preceded by the film version, which we mentioned earlier. This show is considered a major “cultural transposition,” as it transferred the story of the opera to a contemporary African-American setting during World War II. Initially, the events were supposed to take place in the American South, similar to Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess, but the final version moved the action to an umbrella factory and the city of Chicago to reflect the reality of wartime.

The musical featured an all-black cast, changed the names of the characters (Carmen Jones, Joe, Husky Miller, Cindy Lou), and used African-American vernacular in the lyrics. Carmen Jones was a huge commercial success, running for over 500 nights and receiving critical acclaim for its innovative blend of opera and musical theater and its powerful dramatic impact.

***

At the heart of this work lies a historical paradox. On the one hand, it was a tremendous achievement in providing substantial roles for Black actors on Broadway at a time when such opportunities were extremely limited, representing an important step toward empowerment. On the other hand, the process of “cultural crossing/transition” itself, carried out by an entirely white creative team, projected Carmen’s European “exoticism” onto an African-American woman, making her vulnerable to identification with pre-existing racial and sexual stereotypes in American popular culture. For this reason, the play was subjected to black culture, and its use of slang was essential to a critical analysis of potential stereotypes.

The success of Carmen Jones on Broadway demonstrates the power of musical theater to adapt and popularize European opera for American audiences. While this adaptation provided a vital outlet for Black artists and resonated with audiences, the process of adaptation itself navigated complex territory. This work highlights the ongoing challenges of representation within commercial theater, where attempts to achieve cultural relevance and authenticity can intersect with, and sometimes reinforce, prevailing biases and power structures in society.

Contemporary opera trends: radical visions and treatments

In recent decades, opera directors have increasingly approached Carmen not as a fossilized historical artifact, but as a living text open to radical reinterpretation, often using it to comment on contemporary issues.

Calixto Bieito’s Production (various revivals, e.g., ENO 2012, 2015, 2023; Paris Opera 2017; SF Opera 2016): Various revivals, e.g., ENO 2012 English National Opera, 2015, 2023; Paris Opera 2017; San Francisco Opera 2016:

Spanish director Calixto Gálvez’s treatment is one of the most influential and controversial contemporary treatments. Gálvez sets the action in a bleak, contemporary Spain, often evoking the final days of the Franco regime. Pérez strips Spain and opera itself of romantic notions. Pérez’s productions are known for their focus on the primal body, their explicit depictions of sex and violence, and their focus on themes of toxic masculinity, patriarchal control, and the harsh realities faced by marginalized characters.

The stage design is often minimalist or symbolic, emphasizing the bleakness of the environment and the intensity of the human drama. Peito somewhat marginalizes Carmen, attempting to explore the psychology of Don José or the societal pressures that shape the characters’ fates. Carmen Pite’s audiences and critics are often divided, with some finding her work gratuitously vulgar or disjointed. Pite embodies the Regietheater (director’s theater) approach, in which the director’s concept takes precedence in reinterpreting a classic work.

Carmen Barrie Kosky’s Production (e.g., Frankfurt 2016, ROH 2018):

Australian director Barrie Kosky offers a distinctive meta-theatrical treatment. Spoken narration replaces Bizet’s dialogue or recitative in this treatment, and the narration is often delivered by an actress embodying “the voice of Carmen,” drawing on the text of Mérimée and the libretto. This narration creates an alienating effect, framing the opera as a story being told and highlighting its performance history and nature. Kosky uses a hybrid musical score, incorporating material from Bizet. The stage design is often minimalist, dominated by a large, multi-purpose staircase that serves multiple functions.

Kouski draws his aesthetics from diverse sources such as vaudeville, cabaret (evoking Weimar Germany), and perhaps Brechtian theater, emphasizing performance, dance, and theatricality at the expense of psychological realism. The performance is designed to be dominated by dance and features collectivity and striking visual compositions. Carmen Koski has been well received by audiences for his innovation, energy, and new perspective, although some critics find it lacking in character depth or emotional connection due to its conceptual focus.

***

The work of directors such as Peito and Koski shows that the theatrical form in contemporary opera is a dynamic field open to appropriation and interpretation.

They engage strongly with Carmen as a text relevant to contemporary concerns, using directorial concepts to critique social issues (Pietru’s focus on gender-based violence) or to explore the nature of performance itself (Kiski’s theatrical transcendence).

This approach is consistent with the emphasis of appropriation theory on interpretation and the importance of context, ensuring that classic operas such as Carmen remain part of an ongoing cultural dialogue rather than becoming fossilized artifacts. These performances highlight the role of the director as a key adapter, reshaping familiar works to speak to contemporary audiences.