It seems that, over time, the government has succeeded in imposing the term “slums” within the historic city of Cairo. The term is not only used in press releases, but some academics have also begun to use it spontaneously in specialized seminars.

During a lecture on the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood at the American University, a number of prominent academics fell into the trap of generalizing a term that is rejected by many who are interested in the history of Cairo. This is because the historic city does not contain slums, as official accounts claim. Although the debate over the term has not been expanded, its use may give the impression that it needs to be discussed more widely in the coming period to prevent it from seeping into academic studies.

Normalization of the term “slums” in academic discourse

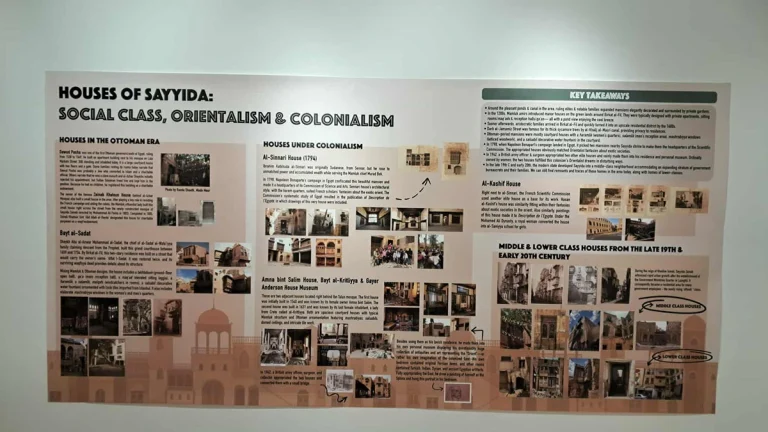

Recently, the American University in Cairo organized an art exhibition entitled “Sayyida Zeinab: History, Urban Development Policies and the Future,” which runs from July 14 to 31. It is the result of a joint collaboration between the American University and Oberlin College in the United States. The aim is to present new historical narratives about the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood using various historical materials, archival materials, photographs, and maps.

The first seminar was moderated by Dr. Zainab Abu-Al-Majd, Professor of Middle Eastern History at Oberlin College. She spoke about the spiritual value of the historic neighborhood and her attempts to document the neighborhood and the Sayyida Zeinab Mosque, as well as the changes it has undergone since its inception.

In her speech, Dr. Hoda Al-Saadi, professor of Arab and Islamic civilizations at the American University in Cairo, said that the idea for the exhibition came out of a joint workshop between the American University and Oberlin College. Students were trained to document about 10 buildings in the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood by referring to old documents and maps.

She added: “We felt the desire to continue with the project, and we began a second phase by surveying 52 heritage and archaeological buildings in the area, using old photographs and maps from the American University’s rare book library. We treated the ruins as a historical source and tried to provide a vivid interpretation of history to understand the context and political circumstances that accompanied the construction of the ruins and how this was reflected in the building as a whole. We also raised many questions about the political circumstances and how the buildings were used, as well as why some remained and others disappeared over time.”

A living religious heritage

Dr. Amira Abu Taleb, visiting researcher in Islamic studies at the Theology Department of the University of Helsinki, spoke about her specialization in the ethics of the Quran. She pointed out that talking about religion and the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood are inseparable. She believes that part of the neighborhood’s beauty stems from its living religious heritage, which is manifested in what is known as popular piety.

This is reflected in what is known as popular religiosity.

She said, “The area has a heritage that anyone can see, which is evident in the names of shops. In addition, hundreds of devotees visit the Sayyida Zeinab Mosque throughout the day. Visitors never stop coming, even though we don’t know for sure if Sayyida Zeinab ever visited Egypt. Of course, religion has played an important role in shaping the neighborhood’s identity over the years. But despite this, trash and noise are everywhere. So my question is always: how can ugliness be reconciled with religion? What does religion have to do with beauty?

Amira believes that the word “ihsan” mentioned in the Quran has a much deeper meaning. The word appears in various forms in the Quran about 200 times. She adds: “Ihsan is naturally always associated with goodness and beauty. For example, ‘Blessed be God, the best of creators’. The concept of ihsan is reflected in our heritage, as architects paid attention to aesthetics through the use of beautiful Arabic calligraphy, geometric shapes, and floral motifs.

This was evident in religious buildings used for good causes, such as schools, khanqahs, abseela (watering places for animals) and other religious structures. This reflects a harmony between sensory and spiritual beauty, and an imitation of the relationship between humans and the nature created by God.”

Moral apathy

She adds: “Over time, visual ugliness in its various forms has become acceptable even in religious circles. People have become accustomed to visual, auditory, and moral ugliness. This has led to a kind of moral apathy and indifference to the various forms of ugliness we see on the streets. This situation reduces our ability to recognize good and stand up against injustice, oppression, and conflict. But in the end, the causes of ugliness are complex and have religious, economic, social, political, and other dimensions.”

She concludes by saying: “What I wanted to raise is whether religion has energy in the souls of the residents of the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood. Can we ask the question: ‘Can we summon this energy to be a source for a clean future that reconnects religion with the concepts of charity and beauty?

An artificial vision

For her part, Dr. Dina Hussein, a specialist in modern Egyptian history who is working on documenting the history of Alexandria in the 19th century, sees a problem that she noticed during her attempts to document what was captured by Orientalist lenses in the 19th and early 20th centuries. She noticed that the documentation of the ruins was devoid of local people. This suggests that the ruins are timeless, i.e., without historical context.

She said: “These images reinforced the Western perception of the East as static, without history, and depicted the daily life of the indigenous population. Many of these images were collected in albums sold to European tourists. They contributed to the formulation of a visual language that glorified architectural stillness and ignored the complexities of the social and religious life of Egyptians. This visual disregard for the local population was no accident. Orientalist images created an artificial vision, presenting Islamic and ancient Egypt as if frozen in a time outside of history. It is true that early photographic techniques favored static subjects over moving ones. But the exclusion of the local population was part of a broader colonial project.

Colonial photographic practices

Dina goes on to say that the production of photographs at this time was the result of both ideological and technical factors. The exclusion of local people from the frame was central to the imperialist colonial gaze. This gaze persisted even after the technical limitations of photography were overcome.

Looking back at these images today forces us to rethink. It is a moment that helps us understand how colonial photographic practices contributed to the formation of archival memory and visual history. Orientalist photographers did not take pictures to preserve local memories or as props for memory. Rather, they focused on the archaeological and architectural features of the place.

Therefore, we must treat these images with caution, because the photographer’s lens is not necessarily a mirror of reality. This raises the question: what does the image show? And what does it hide? When we deconstruct the Orientalist image of Egyptian antiquities, we are not only examining its aesthetic and architectural presentation. We are also analyzing the colonial logic behind it and understanding how it was used within the colonial product that produced it.

But it is also important to pay attention to the possibility of using these images to restore an alternative social history. By asking new questions about the local population, such as: Who were they? How did they live? What was their relationship to this place and this monument? What has it become?

A bird’s eye view

Dr. Mai El-Ibrashi, founder and chair of the Majawara Association for Urban Thinking, believes that the Sayyida Zeinab neighborhood and its surroundings are characterized by buildings of historical and heritage value with a religious and spiritual dimension. She says, “The local residents feel a sense of ownership of their religious heritage. It is a deep-rooted popular sentiment that reflects the existence of a vibrant community. This is in contrast to the Kasbah district, for example, which has been emptied due to tourism. Many of its residents have also left for other areas due to neglect in previous periods.

Mai refuses to describe these areas as “slums,” emphasizing that they are historic, unplanned areas. She says: “The residents of these historic areas are often looked down upon. But the reality is that these areas are the product of a complex set of political, economic, and social circumstances. Historic Cairo is a living heritage, not just ruins. Although I am saddened by the loss of heritage and historic buildings every day, I believe that the continuity of historic Cairo as a living heritage is much more important than the construction of new buildings that do not reflect the local population. I believe that the continuity of historic Cairo as a living heritage is much more important than the construction of new buildings that do not reflect the local population.

Urban policies

Dr. Dalia Wahdan, professor of urban anthropology at the American University, explains that urban policies after 1920 contributed to the deterioration of historic buildings and the removal of many of them. She says, “There was significant demographic growth within these historic areas, and new generations grew up there with no connection to the place. But what I noticed during my work on studies of unsafe areas was the emergence of what is known as the national map of unsafe areas. This map is constantly changing as new areas are usually added to it, but unfortunately, many of these areas that are being added are located within the historic area of Cairo.

She adds: “The government is adopting the wrong policies in dealing with these areas, such as removing monuments and heritage sites and replacing them with other buildings, completely transforming the area, such as Fustat Hills, Fustat Residence, and Arabesque Fustat. Old buildings are also being demolished in record time, so I fear that we will reach a day when the only source of documentation will be Orientalist photographs. We are currently pursuing a vision that the residents of these areas are against heritage and monuments, while the reality is that there is a policy called religion versus nature.

Land for debt

Completes: It is no secret that the state is heavily indebted; therefore, the government is dealing with debt in a different way. The only commodity that can be exchanged for debt is land, and unfortunately, this land is often full of heritage or nature, such as Siwa. The state has already signed such agreements and entered into partnerships with institutions related to heritage and nature, which influence government policy.

She concludes: Therefore, the government is resorting to changing its institutions, such as by creating the Slum Development Fund, which has become responsible for the development of many heritage areas, such as Arab Al-Yasar, Tal Al-Aqrab, and Darb Al-Labana. A large part of these areas will be demolished within a few months. I therefore believe that the institutional changes currently underway are weakening the institutions in which we had placed our hopes for the preservation of our heritage.

Preserving the urban fabric

Dr. Dalila Al-Kurdani, professor of architecture at Cairo University, pointed out that there is still a real opportunity to benefit from successful urban experiences in dealing with heritage issues. She noted that the Imam district has been completely transformed in just two years as a result of the removal of its historical layers.

Despite the committees formed by the prime minister to find solutions for the Jabanat area, the committee’s decisions were ignored and the cemeteries were demolished. Al-Kurdani stresses the need to develop a strategy for each historic area within Cairo and not to treat these areas in the same way.

She says: “Every urban area and fabric is linked to activities and services, and these places are very easy to connect to each other and facilitate access for pedestrians. However, as a community interested in its heritage, we must all start a real dialogue about the importance of improving the lives of local residents within heritage areas while preserving their character and urban fabric.”

Read also:

Will UNESCO list St. Catherine’s Monastery as an endangered heritage site?

After the St. Catherine’s Monastery crisis, has Khaled El-Anany lost the battle with UNESCO?

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://accounts.binance.info/es-MX/register-person?ref=GJY4VW8W

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.