Cairo fires: a long history and perpetrators always unknown

The fire at the Central Ramses building has stirred up a lot of emotions about the history of fires in Cairo. At many moments and turning points in history, fires have been a turning point in the city’s urban history and the beginning of a new phase in the city’s history that goes beyond a mere fire that destroys a building or several buildings. Sometimes the fire is deliberate, and sometimes it is nothing more than negligence, but the result is the same: Cairo has a history of fires that have changed many of its landmarks.

** **

The first fire here was in a separate city that was quickly swallowed up by Cairo and turned into a suburb. This refers to the city of Fustat (now Old Cairo), which was the political capital of Egypt for three centuries and then became the economic, social, and cultural capital throughout the Fatimid era (358-567 AH/969-1171 AD). 969-1171 AD). However, at the end of the Fatimid era, Minister Shawar decided to burn down the city of Fustat, as he was unable to defend it against the advancing Crusader army. The fire continued to burn in the city for 54 days, and Shawar’s decision marked a turning point. From that moment on, Cairo won the conflict with Fustat, and the former began to grow while the latter declined, until Cairo swallowed up the city of Fustat and turned its remains into a suburb known as Old Cairo or Al-Atiqah. The fire marked the end of the Fatimid state, and three years later, Saladin overthrew their state and established the Ayyubid state.

** **

Cairo, which entered a period of rapid urban development during the Mamluk era (648-923 AH/1250-1517 AD), witnessed several fires throughout this period due to the city’s overcrowding and the backwardness of firefighting methods at the time. The beginning of the Mamluk rule witnessed one of the most famous fires in Cairo. After Ayyub and Shajar al-Durr, the Mamluk prince Faris al-Din Aqta’i, were killed in 652 AH/1254 AD, his Mamluks fled, led by Baybars al-Bunduqdari. Izz al-Din Ayyub tried to capture them and ordered the gates of Cairo to be closed, but they attacked the Qaraqin Gate, one of the city gates in its eastern wall, and burned it down before escaping to Syria. Since then, the gate has been known as “Bab al-Mahrouk” (the Burnt Gate).

Mamluk sources record many incidents of fires in the city due to the Mamluks’ struggle for power. One of the largest fires in the Mamluk era was the fire in the Bulaq neighborhood, which was Cairo’s port and the river entrance to the city through which various goods and supplies were brought in. In 862 AH/1457 AD, a fire broke out and destroyed the landmarks of this ancient neighborhood. The Mamluk historian Ibn Taghri Bardi estimated the losses, saying: “More than thirty quarters were burned, each quarter comprising a hundred houses or more, upper and lower, except for the floors, places, ovens, shops, and so on.”

However, the most famous fires in Cairo during the Mamluk era were those that occurred during the reign of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun (709-741 AH/1310-1341 AD). Although the reign of Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari witnessed the burning of the entire Bataliya (Batiniya) neighborhood in 663 AH/1265 AD, the most famous incident was the fires of 721 AH/1321 AD, which took place during sectarian strife that included many fires that spread throughout Cairo. Many churches were destroyed and many houses, neighborhoods, hotels, mosques, and schools were burned down. The most violent of these fires were in the area between Harat Zuweila and Harat al-Rum, destroying many important buildings, foremost among them the neighborhood of Sultan al-Zahir Baybars outside Bab Zuweila, which is still known by his name today. (under the quarter) despite the disappearance of its name.

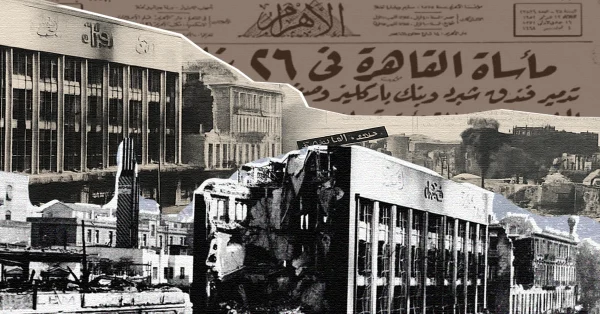

The Cairo Fire

The situation continued in the same vein during the Ottoman era due to the weakness of civil protection measures. However, the modern era witnessed the most famous fires. If the fire of Fustat was a sign of the end of the Fatimid state a thousand years ago, the famous Cairo fire on January 26, 1952, a clear sign of the imminent demise of the rule of the Muhammad Ali dynasty (1805-1953 AD). The fire came amid extreme tensions in the country after Mustafa al-Nahhas abolished the 1936 treaty, which made the British occupation of the canal illegal. This sparked a national resistance movement, to which the occupation responded with a massacre of Egyptian police in Ismailia on January 25, 1952, resulting in the explosion of events in Cairo.

No one knows for sure who was behind the Cairo fire, especially in the area between Ibrahim Pasha Square, Fouad and Suleiman Pasha Streets, and the Nile Palace. Everyone was blamed: the palace, the British, the Free Officers Organization, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the communist movement. The newspapers at the time covered the fire and its aftermath extensively, and historian Abdel Rahman al-Rafei left us a coherent historical account of the events of this fire, which he began in his book Introductions to the Revolution of July 23, 1952: “On Saturday, January 26, 1952, an ominous incident unprecedented in Egyptian history took place: the Cairo fire. This was the first time that a group of the city’s sons set fire to it, under the government’s watchful eye and with its negligence and complacency.”

** **

The events began with popular demonstrations in response to the killing of police officers by the British in Ismailia. The first points of fire were in Opera Square, with an attack on the Opera Casino, which the demonstrators set on fire. Al-Rafi’i says: “No sooner had the fire broken out in the Opera Casino than it spread among the demonstrators, who set fire to nearby places and neighborhoods, and then to other places. The protesters used petrol, gasoline, alcohol, and other flammable materials to start the fires, and the fires were accompanied by looting and pillaging of most of the burning shops.” Al-Rafei lists the streets where the fires spread, which included almost the entire downtown area of Cairo.

The final toll of the Cairo fire was as follows: 300 shops, including some of the largest commercial establishments in Cairo, 30 administrative offices and offices of major companies, 117 business offices and residential apartments, 13 major hotels, foremost among them the Sherp Hotel, 40 cinemas, eight major car showrooms and showrooms, 10 gun shops, 73 cafes, restaurants and lounges, 92 bars, 16 clubs, and one bank, Barclays Bank. The death toll on that day reached 26 people, including 13 at Barclays Bank, nine at the Turf Club, one in front of Barclays Bank, two in front of Omar Effendi’s shop, and one who died during a fire in a shop on Sherif Street. A total of 552 people were injured with burns, fractures, or wounds.

The Cairo fire marked the end of the monarchy. A few months later, the Free Officers Organization succeeded in overthrowing King Farouk, and in 1953, they announced the overthrow of the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the establishment of a republic. With the advent of the republican era, fires continued to ravage Cairo and shape its landscape. Many fires struck companies in a phenomenon that became recurrent and was suspected of concealing corruption that had spread under the pretext of fires that consumed the archives of these companies in a manner that became so repetitive that it was reported by newspapers for decades.

The Egyptian Opera House

However, the fire that marked a turning point in Egypt was the fire at the Egyptian Opera House in the Azbakeya district, which opened in November 1869 as part of Khedive Ismail’s preparations for the opening of the Suez Canal. It remained in operation until October 28, 1971, when a fire broke out in the wooden opera house, which was an architectural masterpiece in the heart of Cairo and one of its most prominent cultural and artistic landmarks. The fire marked the end of an era of sophistication, art, and beauty, and the beginning of an era of ugliness, materialism, and blatant architectural distortion. The opera house was replaced by a multi-story parking garage, whose ugly design reinforced the randomness of an area that had once radiated beauty.

Al-Musafir Khanah

Fires destroyed one of Cairo’s most famous and beautiful buildings. In the streets of the Jamalia neighborhood stood the Masafar Khanah Palace, which dates back to Shahbandar Mahmoud Muharram, a merchant who devoted his vast wealth to building his home between Darbi al-Masmat and Darbi al-Tablawi in 1193 AH/1779 AD. The palace was an architectural masterpiece, distinguished by its extremely precise woodwork. It was even said to have the largest mashrabiya in the entire Islamic world. The photographs that immortalized this lost monument convey some of the grandeur that made the house one of the most magnificent in Cairo at the time. It was even visited by Ibrahim Pasha, son of Muhammad Ali Pasha, and it was there that Khedive Ismail was born. It was then converted into a guest house for state visitors and became known as Al-Musafir Khanah. It remained standing until it was destroyed by a fire of unknown origin in October 1998.

Jamal Al-Ghitani, a native of Harat Al-Tablawi, mourned the loss of the monument that had been his home during his early days in an elegy in the form of a book entitled Istid’at Al-Musafir Khanah (Restoring Al-Musafir Khanah: An Attempt to Rebuild from Memory). An Attempt to Build from Memory). Al-Ghitani speaks of Al-Musafir Khanah with passionate love: “The palace that rivals the Alhambra [in Granada], Iwan Kasra, Topkapi Saray, and Solim Pasha, which we will never find again in the past or present, consumed by sinful flames.” Al-Ghitani, an eyewitness, recounted how the closed palace was neglected and only received some attention on the sidelines of the celebrations of the millennium of the city of Cairo in 1969. It was then handed over to a group of artists to practice their creative work, but then came the fire in October 1998, which to this day no one knows who caused it, ending everything: history, beauty, and art.

Mubarak and the fires of revolution

Before the end of former President Hosni Mubarak’s rule (1981-2011), a huge fire broke out, darkening the sky over Cairo with a black cloud. The building was the Shura Council (the second chamber of parliament). It is not known who was behind the fire, although an electrical fault was the most likely cause. The historic building dates back to 1866, when the Shura Council was established during the reign of Khedive Ismail. However, the flames destroyed the building’s long history. It was later rebuilt in the same architectural style, but the January 2011 revolution quickly overthrew the Mubarak regime, which had witnessed many fires during its era, including the National Theater fire in 2008 and scattered fires in Old Cairo.

Some fires broke out in the heart of the city during the events of the January 2011 revolution. Perhaps the most famous was the fire that engulfed the National Party building overlooking the Nile in Cairo, next to the Egyptian Museum. The fire broke out on January 28. The building, which was built during the reign of Gamal Abdel Nasser, was used as the headquarters of the Socialist Union, and then the National Party, both of which were variations on the tool used by the authorities as a substitute for a healthy democratic life. The revolutionaries targeted the building, set it on fire, and looted it. I was an eyewitness to this. An official decision was then issued to demolish the building, which remained with clear signs of burning on its facade as a symbol of the end of Mubarak’s rule. In 2015, Meanwhile, the Scientific Complex at the entrance to Qasr al-Aini Street was burned down during the events of the Council of Ministers on December 17, 2011. The building housed a huge collection of rare books, which were consumed by the flames.

In the last decade, fires have visited Cairo more than once, especially in old neighborhoods, such as the Al-Ruwei fire in 2016 and the Al-Mouski fire in 2024, which are densely populated commercial areas. The fires came in parallel with the government’s announcement of a plan to develop the entire Azbakeya area, culminating in the fire at the Central Ramses building, a vital building that has negatively affected the lives of all Cairo residents. Dating back to the late 1920s, no one expected this building to have such a decisive impact on the communications network.

** **

This is how Cairo’s history is intertwined with fires, which are not uncommon in cities. However, Cairo is fortunate that most of its major fires occurred at important historical turning points, marking the end of one era and the beginning of another. This feature has given Cairo’s fires their own character, ensuring they remain etched in memory and have a greater impact than mere passing fires. Although Cairo is a city with tremendous vitality, and none of the many fires it has experienced have stopped it from growing and expanding, the fires, which are usually recorded as unknown, have been important and revealing milestones in the city’s history, leaving a much deeper mark on the course of history than the flames themselves.