Carmen’s Timeless Journey: Cinematic Adaptations Through the Ages (2-4)

Reframing Carmen: Cinematic Adaptations Through the Ages

Carmen’s transition from stage to screen opened up new avenues for interpretation and adaptation, taking advantage of the unique possibilities of the cinematic medium. Filmmakers across different eras, genres, and cultural contexts have been drawn to Mérimée’s novel and Bizet’s opera, reshaping its narrative and themes through visual storytelling, performance styles, and cultural transposition.

Applying the lens of appropriation theory, particularly Linda Hutcheon’s concepts of appropriation as interpretation and creativity, as well as modes of interaction (“narration,” “display,” “interaction”) and critiques of fidelity or loyalty to the original text, allows for a nuanced understanding of these cinematic transformations. Film quotations mostly shift to the “display” mode, relying on visual and auditory elements rather than the primarily verbal “narrative” mode of the novel or the mixture found in opera. This shift requires creative choices that go beyond mere fidelity and adherence to the source text, a concept often considered unproductive in studies of appropriation.

Silent visions: early cinema engages with Carmen

The silent film era saw a notable interest in Carmen, with famous adaptations demonstrating cinema’s flourishing relationship with established art forms such as opera and literature.

Cecil B. DeMille’s Carmen (1915): The film starred Geraldine Farrar, a famous soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, a strategic move to lend prestige to the then relatively new medium of cinema. The film was based on a screenplay by William C. DeMille that was closer to Mérimée’s novel than to Bizet’s opera. This version presented Carmen as more manipulative and less sympathetic. DeMille emphasized spectacle and realism, using large crowds and outdoor locations, which were particularly evident in the staging of the bullfight.

The film’s visual language focused intensely on the physical and sensual, in keeping with Farrar’s performance, which critics noted embodied Carmen’s vitality and “demonic” nature. Despite the inevitable loss of Farrar’s singing voice, the film was seen as enhancing her physical presence through the intimacy of the camera. Critics praised the film, calling it “an icon of its time,” greatly enhancing its artistic status.

***

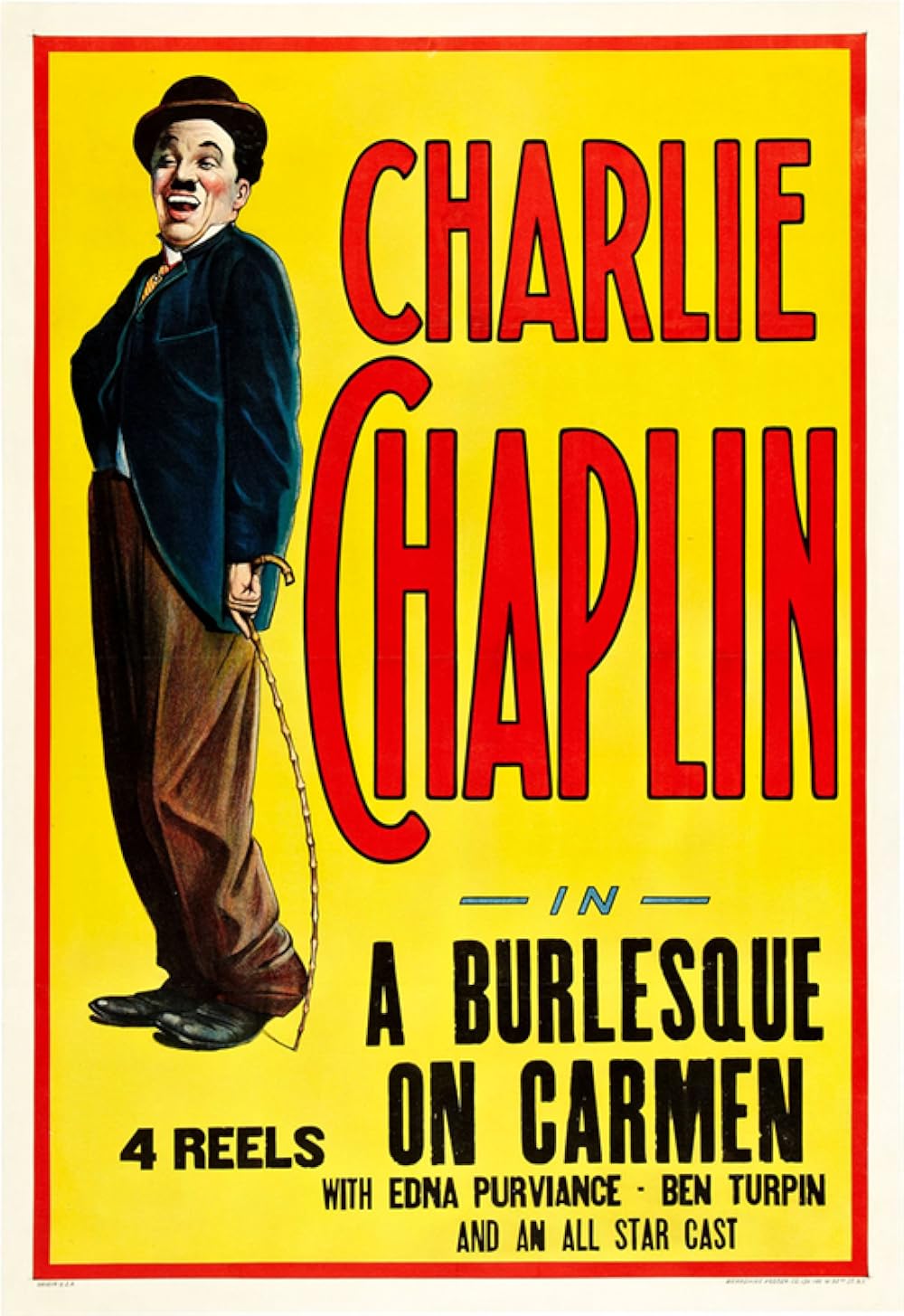

Charlie Chaplin: A Burlesque on Carmen (1915/1916): Released shortly after Demille’s film, Chaplin’s comedy was a direct parody of Demille’s work.

Starring Chaplin as the incompetent officer “Darn Hosiery” and Edna Purviance as Carmen, the film mimics Demiel’s plot points, sets, and visual style, but turns them to comic effect. Purviance offers a caricatured portrayal of Farrar’s more operatic persona, while Chaplin uses slapstick comedy, breaks the fourth wall, and performs “gags” such as interrupting the narration to have a drink at a bar. The film culminates in a meta-cinematic joke where it is revealed that the fatal stab was fake.

While Chaplin’s original version is considered a major development of his comedic style, the tables were turned when, after Chaplin’s departure, Essanay Studios expanded the film and turned it into a longer version. The new version was heavily criticized after scenes were cut and a new subplot was added featuring a gypsy character played by Ben Turpin, which led to lawsuits.

***

These early films reveal a complex dialogue between the emerging art form and its predecessors. DeMille sought to elevate the medium of film by borrowing the prestige of opera and its stars, emphasizing cinematic realism and spectacle as one of the advantages of theater.

Chaplin, on the contrary, used parody to affirm cinema’s distinctive comic potential and capacity for self-commentary, emptying the source material and DeMille’s adaptation of their inherent melodrama. Thus, the two examples above illustrate that appropriation is not mere retelling, but a dynamic dialogue and critique between media.

Mid-century reimagining: race and musical theater

The mid-20th century saw an important American appropriation that transported Carmen into a new cultural and racial context, raising complex questions about representation.

Carmen Jones by Otto Preminger: Carmen Jones (1954): This film adapted Oscar Hammerstein’s successful 1943 Broadway musical, which had already transposed Bizet’s opera to an African-American setting during World War II. Preminger’s film was shot in Technicolor and Cinemascope and starred Dorothy Dandridge as Carmen Jones, a worker in an umbrella factory, and Harry Belafonte as Joe, a soldier who aspires to become a pilot.

The film retained Bihler’s music but used Hammerstein’s English lyrics and was filmed in a southern military area and in Chicago. Preminer wanted to present a “dramatic film with music” rather than a light musical. The film was a huge commercial success, proving the viability of films with an all-black cast. Critics praised Dandridge’s performance, and she was nominated for an Oscar.

However, the film also drew criticism. Critics such as James Baldwin pointed to the absence of authentic black musical styles (jazz, blues, gospel) and argued that, by excluding black characters and context, the film created a separate world that failed to address American racism directly.

Furthermore, some felt that the adaptation painted stereotypical and potentially racist images of the 19th century (Carmen as a hyper-sexualized and “primitive” gypsy woman) onto its Black characters. Despite these criticisms, Carmen Jones remains a landmark film, both for its casting choices and as a powerful 1950s melodrama that explores themes of freedom, conformity, and desire within a specific cultural environment.

***

The case of Carmen Jones exemplifies the complexities inherent in cultural crossings, particularly with regard to race. While the adaptation offered unprecedented opportunities for Black performers in Hollywood at the time, it also navigated the constraints of the era and the problematic legacy of its source material. Complexities also emerged in the way Carmen’s marginalization was portrayed within an African-American context.

The adaptation also risks reinforcing harmful stereotypes, particularly in relation to sensuality and “primitivism.” The creation of an exclusively Black world within the film avoided a direct confrontation with the reality of systemic racism in America at the time. The above situation highlights the dual nature of such quotations, which can be a means of representation and cultural crossover, but can also perpetuate stereotypes if not critically engaged with the biases of the source material and the power dynamics of the new context.

European directors’ perspectives: deconstructing the story

In the second half of the 20th century, many prominent European directors turned to Carmen, using the story not merely as a source of inspiration, but as a vehicle for their distinctive cinematic visions and thematic explorations.

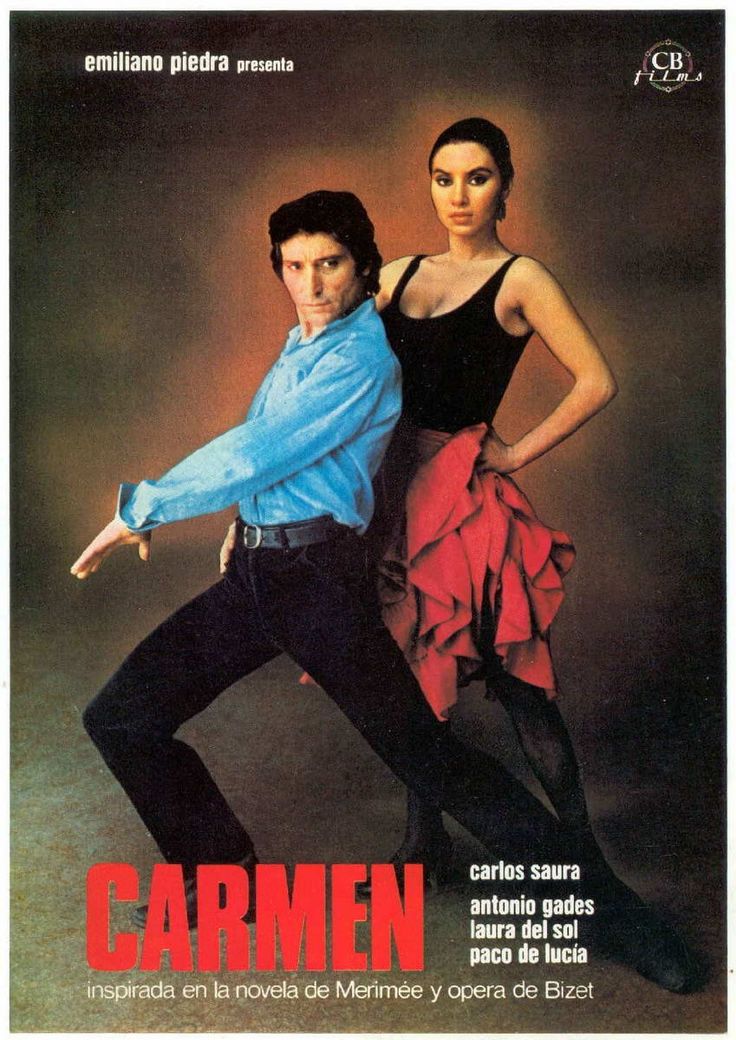

Carlos Saura’s Carmen (1983): Part of his famous “Flamenco Trilogy,” Saura’s film presents a meta-narrative structure, depicting a flamenco troupe rehearsing a ballet based on Carmen, starring and choreographed by the brilliant Antonio Gades (as Antonio, the choreographer/Don José) alongside Laura del Sol (as Carmen, the dancer chosen for the lead role). The film interweaves rehearsals, the dancers’ real-life relationships, Bizet’s music (often played by Paco de Lucía on flamenco guitar), elements from Mérimée’s short story, and the energy of flamenco dance.

Set in a dance studio in Madrid, the film attempts to reclaim Carmen’s story for Spanish culture, using flamenco as an authentic starting point in contrast to French/operatic clichés about Spain. Saora masterfully blurs the lines between performance and reality, art and life, as Antonio becomes increasingly obsessed with Carmen, mirroring the fate of Don José.

The film was praised by the film community for its exquisite choreography, emotional performances, innovative approach to dance-based films, and successful use of flamenco as its primary narrative language. The film became a powerful example of appropriation from a cultural criticism perspective and of re-production.

***

In contrast to Saura’s meta-narrative, Rosy presented a lavish and relatively faithful visual adaptation of Bizet’s opera, with the aim of bringing its drama and intense emotion to a wider cinema audience. The film stars opera stars Plácido Domingo as Don José and Julia Migenes-Johnson in a fiery portrayal of Carmen.

The film used the original score conducted by Lorin Maazel as well as the libretto. Rossi, known for his realistic cinematic style, set the opera in the authentic landscapes of Andalusia, filming in locations in Ronda and Carmona. He used natural light and architecture to enhance the drama and visual narrative. He also used various cinematic techniques to navigate the operatic structure and add layers of meaning. The film successfully blended the operatic atmosphere, with choreography by Antonio Gades, with cinematic realism, resulting in a critically and commercially successful opera film that was universally praised for its explosive energy, performances, and visual beauty.

***

Film: Prénom Carmen by Jean-Luc Godard Jean-Luc Godard, Prénom Carmen (1983): Godard’s Prénom Carmen represents a radical departure from traditional adaptation and can be seen as a deconstruction. Godard loosely draws inspiration from the original story, abandoning the Spanish setting and Bizet’s music (replacing it with Beethoven’s string quartets). Carmen is reimagined as Carmen X, a member of a mysterious terrorist group planning to rob a bank to finance a film. and gets involved with a security guard named Jacques Bonnaffé. Godard himself appears as Carmen’s “Uncle Jean,” a failed film director living in a mental hospital.

Set in contemporary Paris and by the sea, Godard uses his signature style: fragmented narration, a separation between sound and image, and explorations of love, violence, language, and the nature of cinema itself, challenging hierarchies (sound versus image, gender roles).

First Name: Carmen won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. It is an experimental work that uses the story of Carmen as a “leitmotif” (in the Deleuzian sense) to explore broader philosophical and aesthetic concerns. This means that the original story is not treated as a “sacred text” to be faithfully quoted, but rather as a recurring point of reference: Instead of telling the traditional story of Carmen in a linear fashion, Godard takes elements from the story (a destructive love affair, a free woman, a man destroyed by passion, violence) and recycles them or refers to them repeatedly, but not necessarily in a logical or traditional narrative sequence. It’s like a recurring motif in the background, or a slogan that pops up at different points, but it’s not the only focus of the work.

***

The diverse approaches of Saoura and Rosie demonstrate Carmen’s ability to function as a powerful vehicle for artistic expression. Each director presents the story through their established cinematic language and thematic concerns. Saura explored Spanish identity and the art/life duality through flamenco; Rosy combined the operatic tradition with his trademark cinematic realism; Godard used narrative fragments to continue his deconstruction of the language of cinema and his critique of modern society.

These films confirm that quotable texts and different approaches are fertile ground for filmmakers to express their different visions and engage in cultural treatments, proving the enduring flexibility of old stories and narratives and the importance of their modern treatments, which go far beyond their origins.

Contemporary reimagining: genre, culture, and identity

Modern film adaptations continue to demonstrate Carmen’s adaptability to different treatments, transporting the story to new genres and cultural contexts, often with a focus on contemporary identity politics.

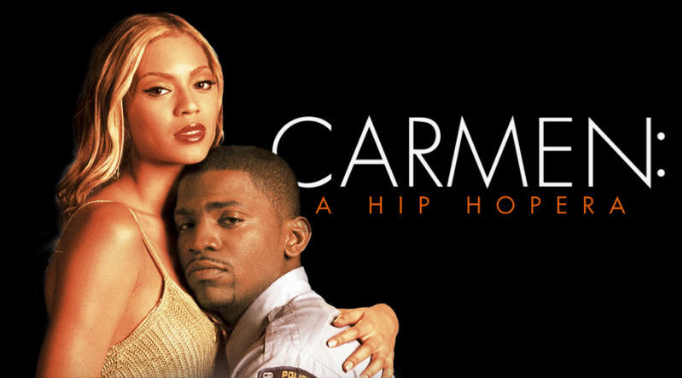

This MTV-commissioned film reimagined Bizet’s opera in a contemporary African-American setting, primarily in Philadelphia and Los Angeles. Starring Beyoncé in her first acting role as Carmen Brown, an aspiring actress, alongside Mekhi Phifer as police sergeant Derek Hill, the film transposed the narrative into the language and expressions of hip-hop and R&B in the early 2000s.

The film features appearances by prominent artists such as Mos Def, Rah Digga, and Wyclef Jean, and tells its story largely through musical numbers, mimicking the visual style of music videos of the era. The film is loosely based on Carmen Jones.

The film dealt with themes such as police corruption and the pursuit of fame in an urban setting. Beyoncé’s film debut was one of the main attractions for the target audience. The film received mixed critical reception, particularly for its soundtrack. It was praised by some as an important “black production,” but was also criticized for potentially reinforcing stereotypes of black women.

***

Carmene Khayelitsha U- by Mark Dornford-May CarmeneKhayelitsha U-(2005): This South African film offers a remarkable re-contextualization of Carmen, in which we see Bizet’s opera set in a contemporary small town outside Cape Town. The libretto was translated and performed entirely in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s official languages. The film masterfully blends Bizet’s music with traditional South African musical styles and instruments. The film is directed by Mark Dornford-May, based on his stage production, and stars South African artists, including Pauline Malefane as Carmen and Andile Tshoni as Jongikhaya (Don José).

This excerpt presents Carmen not as a mere seductress, but as a strong, independent black woman navigating the complexities of life, love, and independence in a post-colonial patriarchal society. Critics praised the film for its energy, originality, and outstanding performances, and it won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. The film is considered an example of successful and distinctive cultural crossover, offering an authentic perspective that challenges stereotypical readings of Carmen’s character.

***

These contemporary films showcase a remarkable movement toward rethinking cultural appropriation, taking a classic European work and reimagining it through the experiences, languages, and musical traditions of Black communities in the United States and South Africa. This process involves more than just a change of scenery; it is a fundamental translation of the narrative into new cultural adaptations.

The resulting hybrid forms—blending opera with hip hop or zosa—reflect contemporary cultural fusion and highlight the role of appropriation as a powerful tool for emphasizing the cultural factor. By translating Carmen into these specific vernaculars, the films transport the story to new audiences, explore its universal themes within their pressing social and political realities, and thereby challenge the Eurocentric hegemony of the original and affirm the story’s enduring global resonance.

Read also:

The Timeless Journey of Carmen: Global Quotations and Cultural Reinterpretations (1-4)