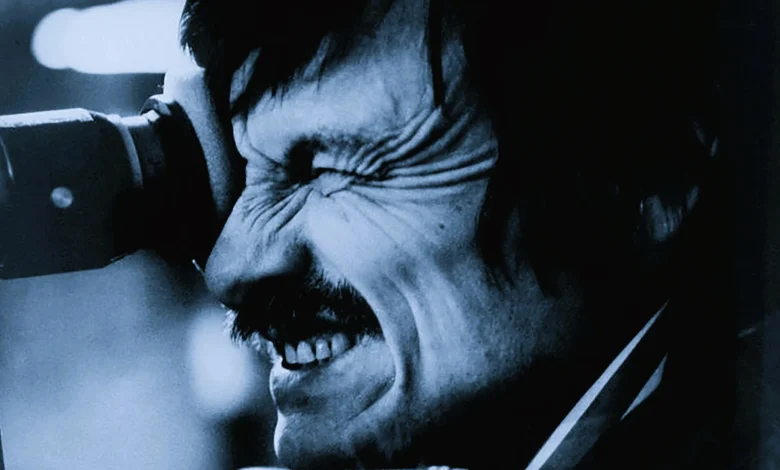

Andrei Tarkovsky: The rebellious director in search of the soul

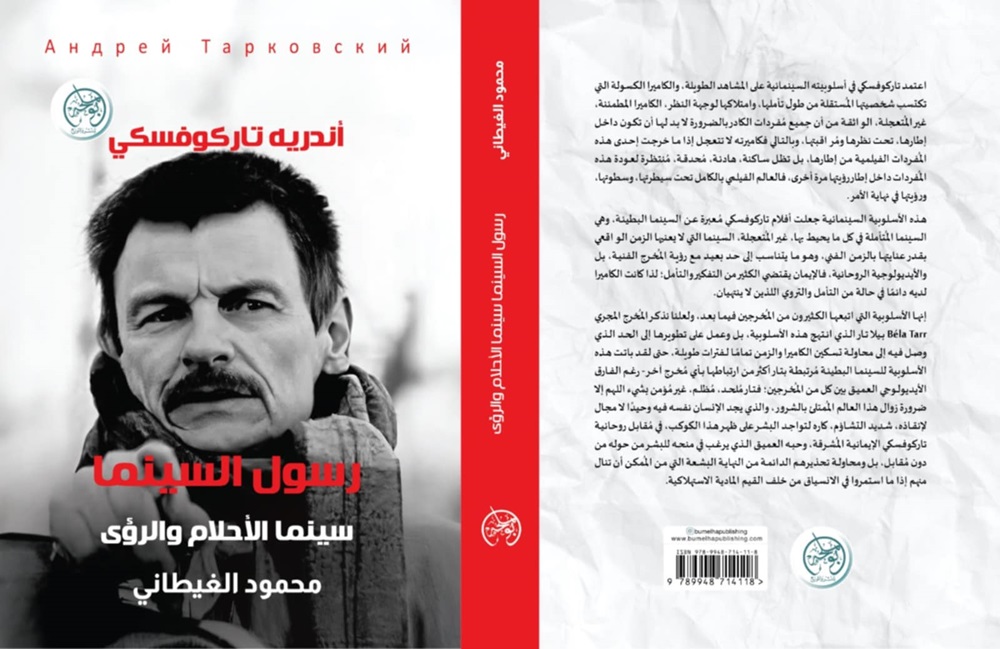

This is a new book published two months ago by Mahmoud Al-Ghitani and published by Boomelha Publishing House, which was recently founded by Emirati novelist Obaid Bu Melha. The book is titled Andrei Tarkovsky: Messenger of Cinema, with the subtitle Cinema of Dreams and Visions. It is not new for me to mention Mahmoud Al-Ghitani’s tremendous efforts in his books on cinema, including “Cinema of the Road: Models of Arab Cinema,” “Clean Cinema,” “The Industry of Noise,” “Cinema of Expired Feelings: Wong Kar-wai,” and “The Philosophy of Cinema: Bela Tarr.” I have written about many of them. Add to that his literary studies, short story collections, and novels.

The book comes at a time when the author is making a tremendous effort in his social and cinematic research. The book is divided into five sections, the first of which is “The Shattered Mirror of Prophecy” about Tarkovsky’s journey in cinema since he was a student at the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography. He grew up in the 1950s, a period referred to as the Khrushchev Thaw, when Russian society became more open to foreign films, literature, and music. This is where he grew up, surrounded by Italian neorealism, the French New Wave, and directors such as Japan’s Kurosawa, Spain’s Buñuel, Sweden’s Bergman, and others. However, despite this, the journey was not easy.

The Soviet Union still had censorship that prevented any reference to the materialistic intellectual heritage of communism. Contrary to everyone’s expectations, he was searching for the soul and its manifestations in cinema, far from any propaganda for the state, its party, or its army. He was preoccupied with humanity and its existence in this world, and the manifestations of the soul through memory and art. He was passionate about discovering a new style far removed from the traditional methods of filmmaking. This was evident in his first film, The Killer, which he directed with his colleague, Greek director Marika Pico, and Russian director Alexander Gordon. It was a 19-minute film based on a story by Hemingway, and it was the first time a film had been produced that was not of Russian or Soviet origin.

The film contained negative scenes, and had it not been for Khrushchev’s thaw, he would have had no choice but to stop or leave the country. He did leave later when censorship restricted what he could present, demanding that scenes be deleted or delaying the film’s release for years. He spoke of studies he did not complete in Arabic and was more interested in a research mission to work as a geologist for a year in the Krasnoyarsk region to search for minerals, especially diamonds. This was one of the reasons for his inclination towards cinema to portray it, so he wrote the script and then worked in film directing. He had a subjective vision that led him to criticize science fiction films. Naum Kliman, director of the State Museum of Cinematography in Moscow, said of him that Tarkovsky arrived at the right time, after we reached a dead end in 1962 despite the thaw brought about by Khrushchev.

** **

We walk among his views on cinema and its vocabulary, such as soundtrack and montage, and his disagreement with Eisenstein’s approach. The message is not a direct glorification of the authorities, but a manifestation of the spirit. Later, the message in his films was the moral issues he raised. He was attracted to people who wanted to serve a higher cause and were unable to participate in prevailing beliefs. People who believed in the struggle against the evil within us.

He considered himself one of the prophets who had a mission to fulfill towards humanity, and it was said that he believed in spirits so much that he participated in séances. This is where his hostility towards Soviet censorship came from, as it contradicted his materialistic philosophy. Thus, his crisis with the Soviet authorities was not political but rather a deeper ideological one, and this is where the metaphysical concerns in films such as Andrei Rublev, The Mirror, and The Pursued emerged, earning him the disfavor of the Soviet authorities. This hostility manifested itself, as I mentioned, in the deletion of his films, the delay of their release, or their screening in marginal cinemas.

** **

His first feature film, Ivan’s Childhood, released in 1962, brought him international fame. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and became a symbol of freedom of expression in Russia. They couldn’t stop him, but they made life difficult for him so that he would leave the country. He was always unemployed or paid a pittance. His departure was not so much a challenge to the authorities as a search for his own identity. The Childhood of Ivan not only provoked the Soviet authorities, but also Italian communists, who accused it of promoting Western individualism, which was contrary to communist values. The Italian newspaper La Repubblica took up the cause, but Jean-Paul Sartre entered the fray in defense of the film. Details of these battles and how the film influenced filmmakers around the world and Tarkovsky himself. Of course, he was not the only one to suffer official persecution and obstruction, but other filmmakers did as well.

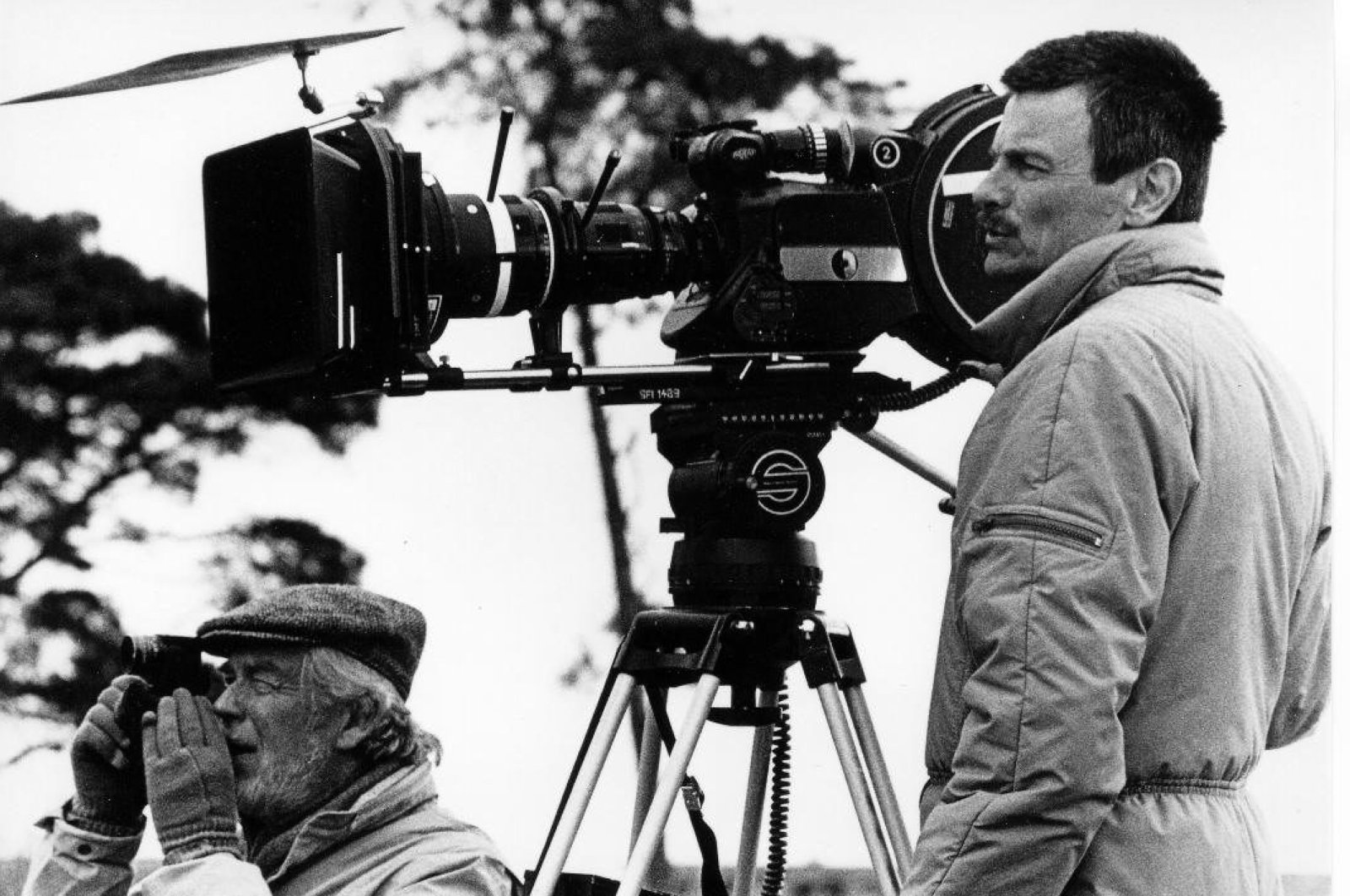

Getting the film approved by the censors was hard work. However, despite this, the Soviet authorities were unable to prevent Tarkovsky from making more films after his first film, Ivan’s Childhood, due to the status he had gained with this film, but as we have said, they turned his life into hell. Mahmoud Al-Ghitani discusses all of this and highlights the spiritual tendency that Tarkovsky embraced, which some saw as arrogance because it did not conform to the official norm. He also discusses issues of cinematic style and Tarkovsky’s differences in this regard, as well as his use of artistic paintings within the film frame to extract new meanings that they did not originally carry. He also discusses the camera and its role as a living being capable of contemplating details and conveying many meanings. He shares his opinion on colors in film and how color film is nothing more than a commercial gimmick, arguing that in black and white, color imposes itself on you, unlike in real life, and that filmmakers must therefore play with colors and use them in different ways.

** **

Of course, there are comparisons between him and other directors such as Béla Tarr, Ingmar Bergman, and others, and how his images emerge from his poetic urgency and deep philosophy. In all of this, he seeks absolute artistic perfection in his philosophical sense, saying, “The aspiration to the absolute is the driving force of the human race, and realism in art comes when the artist strives to express the moral ideal, for realism struggles for truth, and truth is always beautiful. The aesthetic coincides with the moral.”

There are films that were not opposed by the authorities, such as Solaris, which he directed in 1972. They saw it as a form of sovereignty for Soviet cinema in contrast to Western cinema, the human counterpart to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The issue of the film and the novel, and how the dispute arose between him and the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem, author of the novel Solaris, is that he believed the director had the freedom to see the novel cinematically, as he was the sole creator. The battle between them was fierce, and we argued a lot about it.

Cinema is not entertainment, but rather an emotional experience that guides the viewer to the meaning of their existence on this planet. It brings them back to their humanity and allows them to enjoy spirituality. He also discusses his concept of time and the confusion that seems to arise from its reliance on memories. This was also a reason for increased censorship of his films, as they were seen as surreal and incomprehensible. Despite emigrating from the Soviet Union, where he made only five films in seventeen years between 1962 and 1979, he made only three films outside the Soviet Union, including his only documentary film, “Journey Through Time.” How was his defiance of the authorities the reason why his films inside the Soviet Union were more beautiful than those outside, contrary to everyone’s expectations?

** **

The journey with his films comes in the following chapters. It begins with the film “Ivan’s Childhood,” which he summarizes as the Nazi hell through the eyes of a child. It was his first feature film, as we have explained, and he was the director and screenwriter, relying on his cinematic style based on visions and dreams, shattering the classic form of Soviet cinema. The film was based on a short story by Russian novelist Vladimir Bogomolov. The book mentioned earlier discussed the Marxist attack on the film in Russia and Italy, as the film is not about war and does not promote it, even though it is about war.

** **

Al-Ghitani discusses the film’s composition from the beginning, when the child Ivan appears chasing butterflies and a cuckoo bird and playing with his mother, a dream that the director was keen to capture with bright lighting. Then it suddenly cuts to the current nightmarish reality, where we see Ivan waking up in a windmill where he had been hiding, and when he climbs down, we see him walking among many corpses. He is a traumatized child who lost his mother, sister, and father during the Soviet-Nazi war. Although the film is about war, the war itself is marginalised; we see nothing of it, and the film hardly moves forward, dwelling instead on its nightmarish effects on others. Tarkovsky was then about to turn 30 and had just graduated from the Gerasimov State Institute of Cinematography. With this film, he confirmed his importance as a director capable of inventing a new style. Then came Andrei Rublev, which he called the Russian epic.

Of course, I will not dwell on the details of each film as Al-Ghitani did, but will leave that to you. This epic film comes among many other epic films in the world, such as Ashes of Time by Wong Kar-wai from Hong Kong, In the Mood for Love by Danish director Lars von Trier, Tango by Hungarian director Béla Tarr, and The End of the World Now by American director Francis Ford Coppola, among others. But here we are on a spiritual and existential journey of faith, not war. It is a journey of self-discovery and reflection on the poverty and misery that surrounds the world, through the life of Russian artist Andrei Rublev, one of the most prominent artists of the Renaissance in the Middle Ages and the most talented in painting icons on the walls of Christian churches and cathedrals.

** **

Tarkovsky found himself faced with the unknown history of the artist Rublev and began to imagine his life and the trials and tribulations that may have led him to maturity. Of course, the Soviet authorities were angered by the film and its journey of faith, prompting Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party and President of the Soviet Union, to request a private screening of the film. However, he walked out halfway through, and the film was banned for a long time, only to be released after 20 minutes had been cut. Of course, Brezhnev could not tolerate a film that presented Russia’s brutal history, full of murder and conspiracies against the government, and its defeat by the Tatars during the events of the film and the life of Rublev. They were accustomed to glorifying Russian citizens and extolling Russian nationalism.

** **

We come to the third film, Solaris, about the concept of love and romance. It is, however, a science fiction film and his third feature film in which his spiritual streak comes to the fore. The fantasy here is only superficial, while the subject matter does not stray far from a deep contemplation of the human soul. It is a film based on a novel by Polish writer Stanislaw Lem, which he rewrote as he wished, and this, as we have already explained, was the cause of the dispute between them.

In the film, the planet Solaris is an unknown planet completely covered with water, which is a huge brain capable of thinking. It can even penetrate the minds of the scientists living on the space station monitoring it, and then manifest what is going on in their minds in front of them. The planet Solaris is an advanced intelligence capable of reading the minds of everyone on the space station and recreating them. Tarkovsky’s observation of the scientific revolution around him reminded us of spirituality, meditation, and human connection that does not deny emotions, because humans need their brothers, and this is the deep meaning of love.

As for the film “The Mirror,” its style reminds you of that of American director Christopher Nolan, although they differ in their concepts and aesthetic form. Time flows in the film without a structure that we can grasp; rather, times overlap like a stream of unconsciousness. The film is one of the most introspective films, conveying many memories to us. It is based on free association, which may confuse the viewer at first. It presents itself to such an extent that we hear the voice of his father, the poet Arseny Tarkovsky, reciting passages from his poems in many scenes that correspond to the scene in front of us. He also enlisted the help of his mother, Maria Vishnyakova, in the film to portray the aging mother “Masha.” In other words, he wants to emphasize to the viewer that the film and its events are closely connected to him.

** **

We come to the film “The Chaser,” in which he expresses the existential dilemma of faith as he sees it. He reflects on himself before reflecting on the world, expressing his torment in the search for religious certainty. The feeling of lack of faith leads to self-division and psychological torment, as if he were turning over hot coals. He is in a never-ending psychological struggle between the material and the spiritual, chasing his faith by re-enacting the world cinematically. The viewer who enters Tarkovsky’s world is like someone who has entered a time machine and been transported to a different world that has nothing to do with the world around him.

The Stalker is based on the 1972 novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Of course, Tarkovsky did not adhere to it completely. The title of the film expresses his desire to convey to us the meaning of his pursuit of his faith or certainty.

The film opens with a scene in a bar in neutral black and white, hinting at the psychological misery and suffering of the characters in the film. We see the professor enter the completely empty bar and sit down to drink his coffee. Soon, the film’s opening credits appear with phrases such as “What was that? Nizka? A visit from citizens of the cosmic abyss? and others, preparing the viewer to enter his cinematic world. It is one of his most philosophically dense films, but it represents the most mature stage of his introspection.

** **

As for the film Nostalghia, Tarkovsky died of lung cancer in Paris in 1986. In his self-imposed exile, he lived in a prison of memories of his Russian world. This is clearly evident in the film, as the visions and dreams that began his film Ivan’s Childhood dominate the entire film. Through his films, he conveys something of his autobiography, his life, and his suffering, but here he almost presents himself completely. Here, he follows the journey of Russian writer Andrei Gortchakov, who left Russia for Italy in search of Russian composer Pavel Sovreenov, who lived in Italy in the 18th century and committed suicide upon his return to Russia. Gortchakov is equivalent to Tarkovsky himself, who projected onto him and the characters in the film, such as Suvorov, who committed suicide, the state of division he himself suffered from, reminiscent of Tarkovsky’s statement in 1984 that he would never return to Russia.

** **

Then came The Sacrifice, a prophetic message to heaven. It was his last feature film. Due to his suffering from lung cancer, he did not attend the film’s premiere at the Cannes Film Festival as he was in hospital. There was a sense that he was about to leave this world, which made the film crowded with symbols, visions and surreal religious dreams, as if he wanted to warn the world about the material identity that would lead it to complete destruction. The title of the film is consistent with Christian beliefs. It can be translated as “The Sacrifice,” but “offering” is closer to the concept of the film.

In the film’s opening credits, we see a painting behind the camera depicting the Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo da Vinci, in which one of the kings kneels before the Virgin Mary holding her son Jesus, begging her for mercy. This painting provides a deeper interpretation of the film’s concept. The film is filled with religious symbols and serves as Tarkovsky’s final message to a world mired in materialism and evil. It is a timeless film, despite being released in 1986. The second chapter on his feature films ends, and the third chapter covers his short films made for Soviet television, such as No Vacation Today, followed by the fourth chapter on his documentary films, such as Journey Through Time, and the fifth and final chapter on his short fiction films. The book ends after a wonderful journey with a director who is no longer with us in the Arab world, in which Mahmoud Al-Ghitani, as usual, has made a remarkable research effort that deserves every appreciation.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.