Bastetodon: the Discovery of a 30-Million-Year-Old Predator in Fayoum

Proof that the largest extinct creature once roamed the Egyptian desert was uncovered in February 0f 2025 by the Vertebrate Paleontology Center at Mansoura University. The discovery of the Bastetodon (also known as “Bastit”), was made in the Fayoum Depression and is estimated to have inhabited this land 30 million years ago. Egyptian paleontologist Professor Hesham Salam and his team successfully pieced together the story of this ancient predator, revealing how the landscape was once a stage for nature’s marvels. Bab Masr presents a comprehensive look at this extraordinary discovery.

New Discovery

Dr. Hesham Sallam, founder of the Vertebrate Paleontology Center at the Faculty of Science and a paleontologist at both Mansoura University and the American University in Cairo (AUC), explained: “Climate change has played a major role in shaping the ecosystem we see today. Our new discovery is of a predatory animal that once lived in Egypt—specifically in the Fayoum Depression—30 million years ago. We have named this creature Bastetodon, and we have also reclassified another species from that family, discovered 120 years ago, under the new name ‘Sakhment.’”

According to Prof. Sallam, the discovery dates back to 2020 during an expedition to the Fayoum Depression by the Sallam Lab team. While excavating rock layers estimated to be 30 million years old, team member Billal Salam uncovered several prominent teeth. This find led to the extraction of an exceptionally well-preserved, fully intact 3D skull fossil—free from any distortions. A truly rare discovery for paleontologists, researchers have dedicated five years to determining the identity of the skull’s owner.

New Genus

“Based on precise statistical regression analyses, the Bastet animal weighs approximately 27 kilograms—roughly the size of a modern leopard or hyena. Its robust head muscles, combined with its jaw structure and sharp teeth, place it among top-tier predatory animals,” said Dr. Shorouq Al-Ashqar, the lead author of the study published in the International Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

According to the center’s publication, detailed anatomical studies, statistical analyses, and morphological evaluations have revealed that the discovered skull belongs to a new genus of extinct carnivorous animals, known as the “Hinodonts.” These creatures existed long before the emergence of modern carnivores like dogs, cats, and hyenas. They once dominated the ecosystems of the Afro-Arabian continent—especially following the extinction of the dinosaurs—before eventually disappearing themselves.”

Prof. Sallam continued: “The Fayoum Depression offers a substantial 15-million-year window into evolutionary history, serving as a vital link between ancient species and the ancestors of modern mammals.” The researchers have named this new genus Bastetodon in honor of the ancient Egyptian goddess Bastet—a symbol of protection depicted with a cat’s head. The term “odon” is derived from ancient Greek, meaning “tooth,” alluding to the creature’s sharp teeth.

Reviving Extinct Life

Fossils—often discovered embedded in rocks—offer the only glimpse into the existence of extinct animals. From these remnants, scientists and experts deduce the original appearance of these creatures. In this context, specialists play a crucial role by translating scientific discoveries into reconstructions that closely mirror the animals’ natural forms as they existed millions of years ago, making the ancient past accessible to the public.

In an exclusive interview with Bab Masr, Ahmed Morsi, Salam Lab team member responsible for creating the final depiction of the new discovery, explained that “Bastet is a species within the mammalian group, and we faced many challenges along the way. This animal, which went extinct millions of years ago, belongs to the Hyaenodonta—a group that is similar to, or even more closely related to, bears, dogs, and cats. While most modern carnivorous animals are classified under the order Carnivora, Hyaenodonta is part of a distinct group known as Creodonta, and all these species are mammals.”

He continued: “Bastet is characterized by a mix of features—sometimes resembling those of cats and at other times bears—which left us quite perplexed. That was the challenge. My role is to develop the final 3D depiction of this extinct animal so that it closely mirrors its true form, rather than appearing cartoonish. This process required a significant amount of time and effort on my part.”

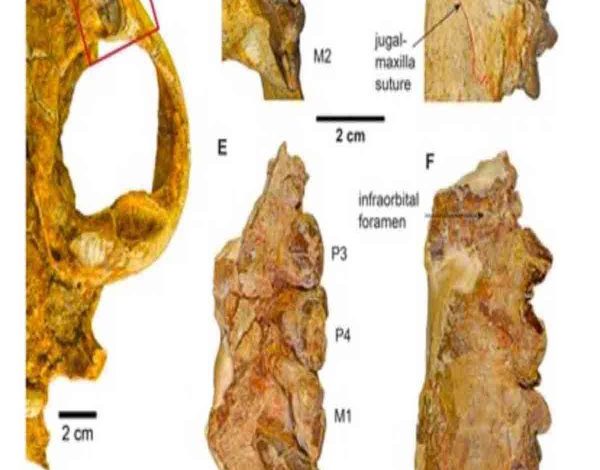

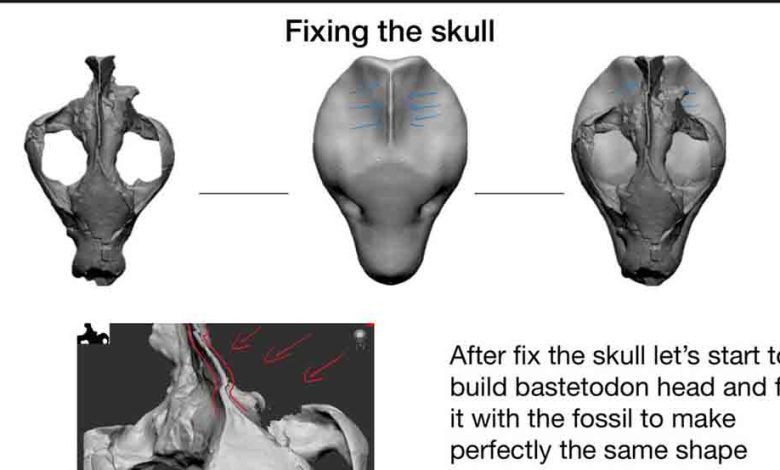

Skull Morphology

According to Morsi, another challenge was reconstructing the shape of the skull. He explained: “As the only Egyptian scientific designer on the project, I had no pre-existing model to follow, so I had to invest considerable time in research and anatomical studies.” He continued: “We only recovered the upper portion of Bastetodon’s skull; the lower part remains unknown. This absence raises several questions—what did the complete skull look like, and what were the specific shapes of its teeth and molars, given that each species has unique dental features? To approximate its form, we examined its close relative within the Hyaenodonta family, Hyaenodon, which possesses an almost complete skull and is very similar to Bastetodon. This served as a valuable reference, especially for reconstructing the lower jaw.”

Morsi further added: “We were fortunate to find its upper teeth, which enabled us to design a model that closely approximates Bastetodon’s actual dental structure. By arranging the teeth in a method I call the ‘Carnassial way,’ our reconstruction is likely to be highly accurate. We also observed that the overall skull morphology resembles those of wolves and bears.”

Bastetodon’s Nose

Morsi explains that there were two competing hypotheses regarding the shape of Bastetodon’s nose. Some envisioned it as resembling the sharp, narrow nose of a cat, while others imagined it as more akin to the puffy nose of a bear. He adds: “This was another challenge for me in finalizing the design, so I looked closely at the anatomical structure and the skull’s morphology.”

Upon examining Bastetodon’s skull and facial muscles, the team discovered the presence of the levator nasolabialis muscle—a feature that differs in configuration from that in cats. This finding suggests that Bastetodon’s nose was more similar to that of bears or dogs, leaning significantly toward a bear-like appearance. Additionally, the animal had five digits on its forelimbs, reminiscent of the modern fossa.

The final sculpting of Bastetodon’s form was a collaborative effort by paleontologists Salam, Al-Ashqar, and Dr. Matthew Port.

Fur Pattern

Morsi explains that the greatest challenge was envisioning the fur of Bastetodon. In this context he states: “some images show Bastetodon with contrasting spots, reminiscent of a jaguar’s pattern, but I believe it likely had a uniformly colored coat without such markings. This portrayal isn’t scientifically based, given our limited understanding of its environment and the fact that the species is extinct. Moreover, if it had developed those spots—as a form of camouflage or protection—it might have improved its chances of survival. Therefore, I suspect its fur was either uniformly colored or exhibited only subtle tonal variations. After all, distinctive spotting is more common in cats, a group to which Bastetodon does not belong.”

Paleontology Center

It is noteworthy that the Paleontology Center at Mansoura University is recognized as the first institution in the Middle East and North Africa dedicated to vertebrate paleontology. Founded by Prof. Hesham Sallam, the center houses an extensive collection of fossils dating back millions of years, including specimens of turtles, dinosaurs, whales, fish, primates, rodents, and various other fossilized organisms. The center is committed to studying the natural heritage of fossils in all their diverse forms.